The purchase of big art and design books requires careful consideration round here, what with shelf space being stressed in multiple ways. (One of the shelves bearing the heavier volumes sags alarmingly.) But this one was recommended to me by a couple of people, and I’d also had a book token hanging around unused for over a year so here we are.

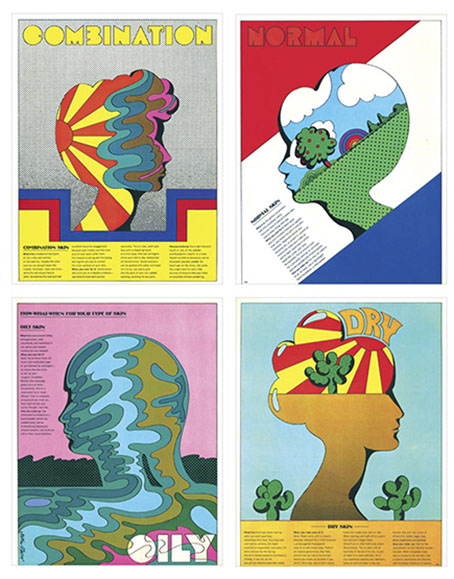

Skin types for Seventeen magazine, 1967.

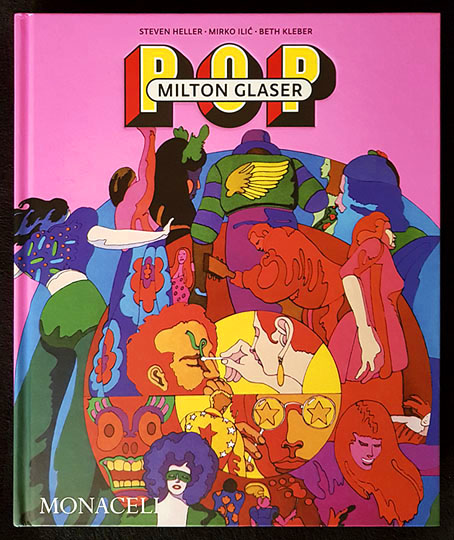

Milton Glaser: POP is a copiously-illustrated 288-page study of the work produced by Milton Glaser and his colleagues at Push Pin Studio, with an emphasis, as the title and cover art suggests, on the company’s prime decade of the 1960s. The book was compiled and edited by the redoubtable Steven Heller, together with Mirko Ilic and Beth Kleber, and presents an overview of Glaser’s remarkable career as designer and illustrator. Glaser was an exceptionally versatile artist, something which has often made appraisal of his career a difficult business. You could easily choose ten of his book or album covers from the many examples assembled by Heller and co., and all would look like the work of different people.

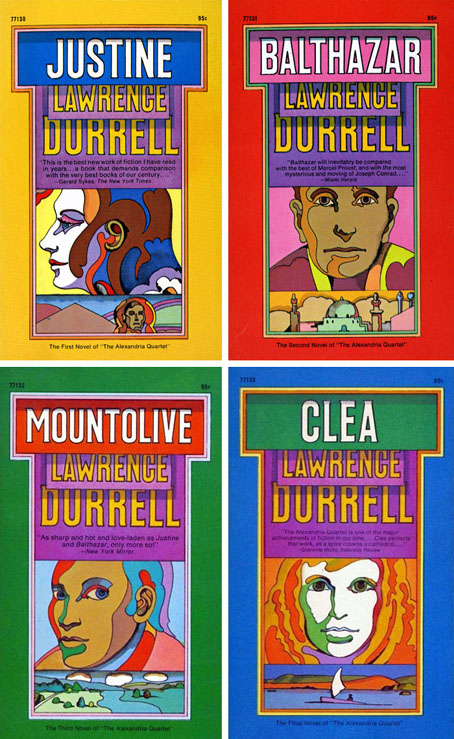

The Alexandria Quartet by Lawrence Durrell; Pocket Books, 1969. I’d much rather have this set than my Faber collection which packages the four books into an unwieldy brick.

Matters are further complicated by the often collaborative nature of the work at Push Pin, and the fact that designers and illustrators aren’t always given credit for their commissions. In the past I’ve gone looking for Glaser’s work then given up when I seemed to be encountering designs that weren’t by him at all. In addition to demonstrating Glaser’s range, Heller, Ilic and Kleber have done everyone a service by showing unused illustrations and crediting work that was previously debatable. Some years ago I wrote a post about the uncredited cover art for the first budget sampler album, The Rock Machine Turns You On (1968), an entry which didn’t manage to resolve the issue of whether or not the cover art was Glaser’s work. It turns out it was by him after all, collage being one of the techniques he employed from time to time.

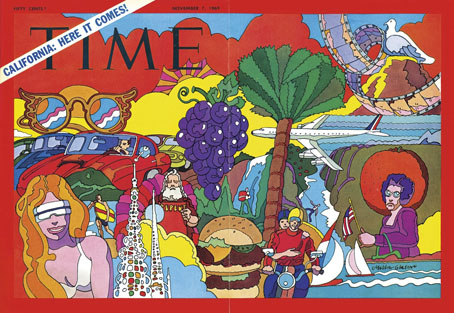

TIME magazine gets groovy. A fold-out cover from 1969.

On a more personal level, Glaser’s versatility and multi-disciplinary approach is encouraging if you find yourself being led in a similar direction. Designer-illustrators are no longer as rare as they used to be, but illustrators, like many fine artists, still tend to develop a favourable style which they then stay with year after year. Illustrators who change their style according to their mood, or the nature of the brief, or a desire to experiment, remain in the minority. Glaser’s illustration ranges more widely than any other artist I’ve seen, from realistic pen-work and watercolour sketches, through bold, stylised designs, to complete abstraction. He could also be playful and frivolous in a manner you can’t imagine from some of his more serious contemporaries, while also being adept enough at illustrating children’s stories that he might easily have spent his career doing this alone.

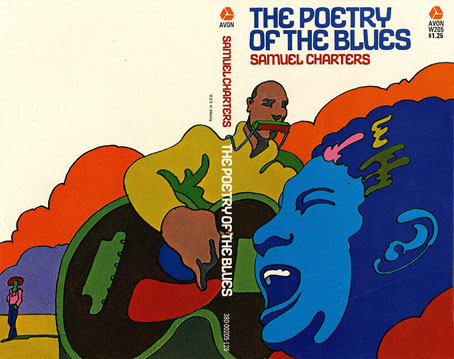

Avon Books, 1970.

But the main attraction of Milton Glaser: POP for this reader is the focus on all those bold graphics, especially the commissions that reworked the emerging psychedelic styles for the commercial sphere. The cover illustration is emblematic of many other examples. This drawing first appeared in a New York magazine supplement in 1967 to accompany an article about LSD, before being reused on the dustjacket of Tom Wolfe’s book about Ken Kesey and friends, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. Glaser and his colleagues at Push Pin were prime exponents of something I’ve taken to calling “the groovy look“, a term I reserve for commercially oriented quasi-psychedelic art. This isn’t meant to be a serious label, it’s a private term that I used to attach to anything resembling the art styles seen in the Yellow Submarine feature film. Serious or not, the label persists when I continue to feel the need for a suitable descriptor for this type of art. “Psychedelic” is the most common label (and one which obviously suits Yellow Submarine) but it seems inappropriate when discussing magazine adverts for household products or illustrations in children’s books. Steven Heller prefers the term “Pop”, but this strikes me as too loose, risking confusion with the many varieties of Pop Art which seldom resemble the vivid, stylised creations of Glaser et al. Pop would also seem misapplied as a description for commercial art when Pop Art was all about the appropriation (ironic or otherwise) of commercial iconography. If you start to label a swathe of commercial art as Pop along with the gallery art that was borrowing from it then the term becomes so diffuse it loses its meaning. The “groovy style” had a long reach, and evolved beyond the decade it was born in. Plenty of examples may be found in the early 1970s by which time Pop Art (in the gallery sense) had lost its momentum.

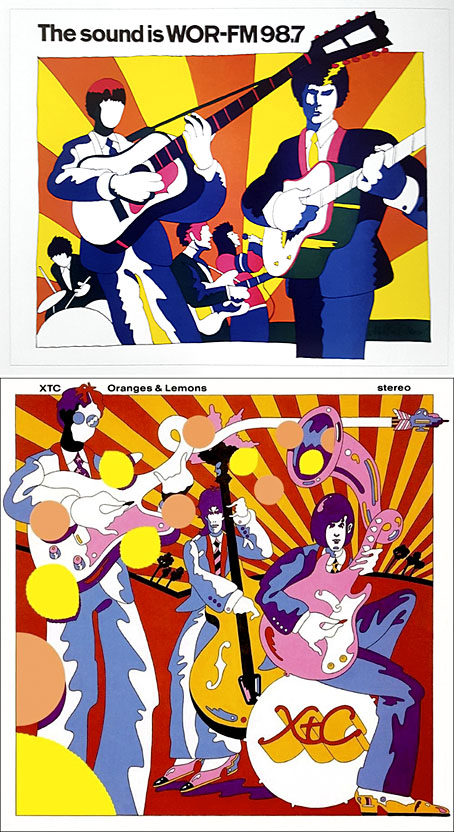

Above: Glaser ad art, 1966. Below: Dave Dragon’s cover art for XTC, 1989.

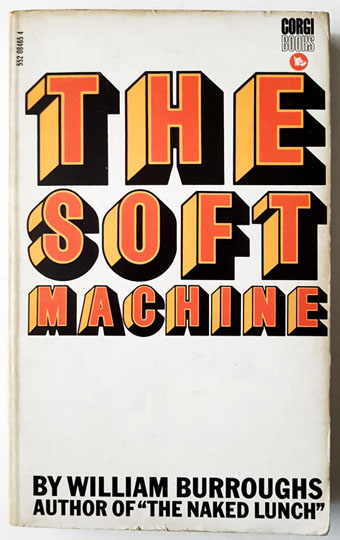

I’ll no doubt return to this question, especially when I’ve just done something in the groovy style myself. (You’ll have to wait a few months before you see the results.) In the meantime there’s a lot to enjoy in this book. I haven’t yet mentioned Glaser’s unused promotional art for the Saul Bass feature film, Phase IV, or the many typeface designs that Glaser created with his associates, and the way one of them—Baby Fat—is used on the cover of the first UK paperback of The Soft Machine. I think this was the first William Burroughs book I ever bought, and it’s been sitting on my shelves all this time without my realising it was a Glaser production. That’s how it often is with graphic designers; they shape our world almost as much as architects do yet their specific influence isn’t always recognised.

Corgi Books, 1970.

And by coincidence, the latest post at The Daily Heller is about a Glaser exhibition tied to the publication of the book. If you’re in New York it’ll be running for the next two weeks.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The groovy look

• Milton Glaser album covers