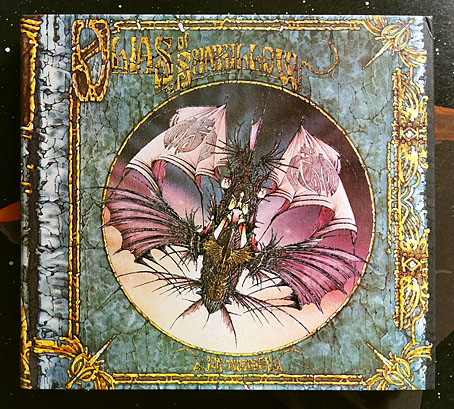

Jon Anderson’s solo debut, Olias Of Sunhillow, is reissued this week in a double-disc set comprising a remastered CD plus an audio DVD. I’d been hoping for some time that this album might be given a proper reissue, it’s one I like a great deal but my old CD has never sounded as good as it ought to. The album may command cult status round here but you don’t see it mentioned anywhere outside Yes forums or partisan enclaves like the Prog Archives. This post may be taken as a small corrective to the neglect.

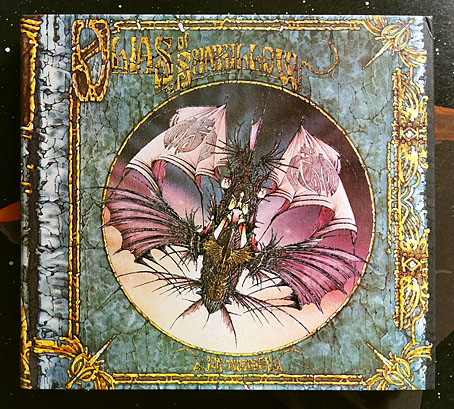

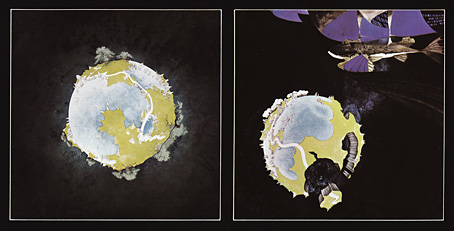

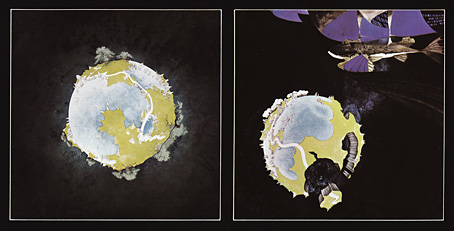

Olias Of Sunhillow was released in 1976, and was the most unusual of all the solo albums recorded by the individual members of Yes in the mid-70s, being a spin-off from some of the group’s early albums, or at least their cover art. Roger Dean’s first cover work for the group was on Fragile in 1971, for which he painted a miniature world rather like one of MC Escher’s planetoids. This was Dean’s idea, the band had suggested a broken piece of porcelain as the cover image. The back cover of the album showed the same planet in a state of fragmentation with a fish-like spaceship floating above it (see below). Another drawing of the fish-ship was added to the front cover before the album’s release, and it’s this ship, and the narrative it suggests, that leads eventually to Anderson’s solo album. Two years after Fragile, the planetary disintegration had turned into an exodus on the group’s triple-live album, Yessongs, the back cover of which shows pieces of planet being towed through space by a similar fish-ship. The other panels of the cover depict the arrival of these fragments on a newer, larger world. Anderson’s album takes this sequence of events then filters them through Vera Stanley Alder’s mysticism to craft a musical odyssey which Discogs describes as:

…the story of an alien race and their journey to a new world due to catastrophe. Olias, the title character, is the chosen architect of the glider Moorglade, which will be used to fly his people to their new home. Ranyart is the navigator for the glider, and Qoquaq is the leader who unites the four tribes of Sunhillow to partake in the exodus.

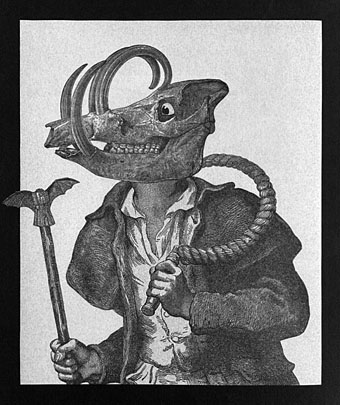

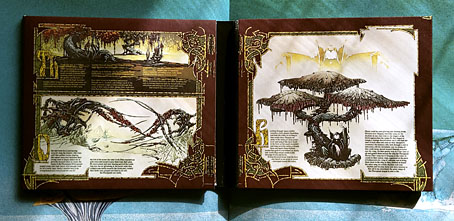

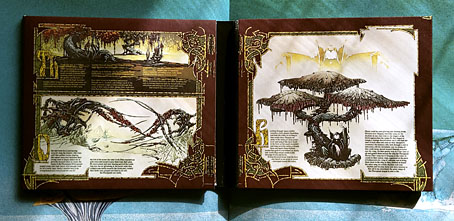

For many years in British music circles it would have been a grave error to even acknowledge this album’s existence, never mind admit to actually liking it. This was partly the old animus against progressive rock, an unexamined prejudice that lasted well into the 1990s, but Anderson’s album had so many strikes against it that it might have stood as the winner of a disapproval lottery for the more ideologically rigid writers and readers of the NME. It’s Jon Anderson (strike 1), the lead singer of progressive rock (2) group Yes (3), whose album is a science fiction (4)/ fantasy (5) concept (6), littered with Tolkien-like invented names and words (7), and with a multi-page sleeve embellished with detailed fantasy illustrations (8) by David Fairbrother-Roe. The design was art directed by Hipgnosis, who subsequently designed the next two Yes albums. Anderson originally wanted Roger Dean to create the packaging, which would have provided a further strike of disapproval against the album, but Dean’s career had gone into overdrive following the publication of Views so he either didn’t have the time or didn’t want to be involved. In Views Dean mentions “another project” based on the fish-ship’s journey which may be a reference to Anderson’s forthcoming album, the credits of which thank Dean for “planting the seed”.

Roger Dean’s original artwork for Fragile (1971). Another fish-ship was added to the final cover art.

Continue reading “Solid Space: Jon Anderson’s cosmic voyage”