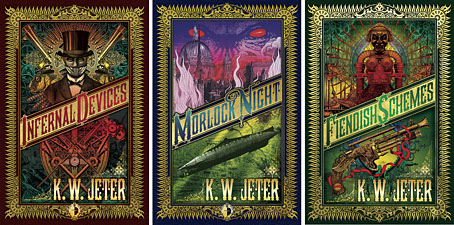

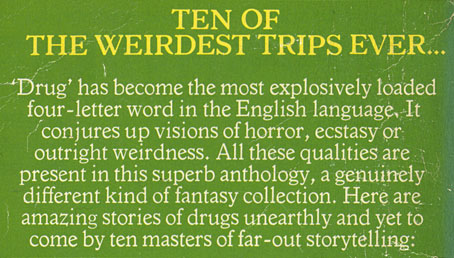

More psychedelia of a sort. Anthologist Michel Parry, who died last year, was a familiar name to British readers of fantasy, horror and science fiction for his themed collections: Beware of the Cat (1972; horror stories about cats), The Devil’s Children (1974; horror stories about children), The Hounds of Hell (1974; horror stories about dogs), Jack the Knife (1975; Jack the Ripper stories), The Supernatural Solution (1976; occult investigators), Sex in the 21st Century (1979), and so on.

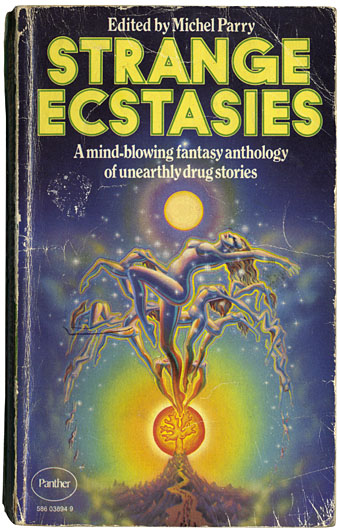

Parry also compiled multi-volume anthologies throughout the 1970s, two of which have always stood out for me: the Mayflower Books of Black Magic Stories ran to six volumes presenting a wide range of occult fiction that included a number of obscure tales from Victorian and Edwardian writers; for Panther Books he compiled three collections of drug-related fantasy and SF stories that are just as varied, and may even be unique for the way they place authors as such as Lord Dunsany and Norman Spinrad together in the same volume. Both series are very much of their time—occult psychedelia!—and are worth seeking out, if you can find them. I emphasise the last point because it’s taken me a while to find a copy of Strange Ecstasies that wasn’t being offered for bizarrely inflated prices; my paperback habit has its limits… None of these anthologies have been reprinted so they’ll become increasingly scarce. For more invented drugs, there’s a good list at Wikipedia.

Cover art by Bob Haberfield.

Strange Ecstasies (1973)

The Plutonian Drug (1934) by Clark Ashton Smith

The Dream Pills (1920) by FH Davis

The White Powder (1895) by Arthur Machen

The New Accelerator (1901) by HG Wells

The Big Fix (1956) by Richard Wilson

The Secret Songs (1962) by Fritz Leiber

The Hounds of Tindalos (1929) by Frank Belknap Long

Subjectivity (1964) by Norman Spinrad

What to Do Until the Analyst Comes (1956) by Frederik Pohl

Pipe Dream (1972) by Chris Miller

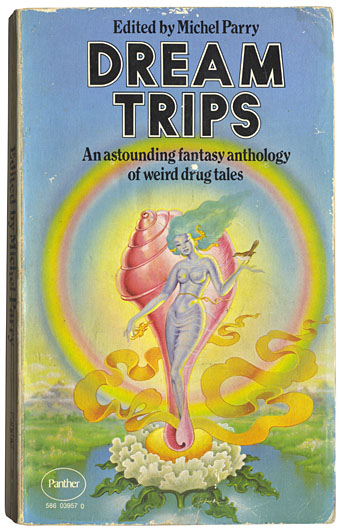

Cover art by Bob Haberfield.

Dream Trips (1974)

The Hashish Man (1910) by Lord Dunsany

As Dreams Are Made On (1973) by Joseph F. Pumilia

The Adventure of the Pipe (1898) by Richard Marsh

Dream-Dust from Mars (1938) by Manly Wade Wellman

The Life Serum (1926) by Paul S. Powers

Morning After (1957) by Robert Sheckley

Under the Knife (1896) by HG Wells

The Good Trip (1970) by Ursula K. Le Guin

No Direction Home (1971) by Norman Spinrad

The Phantom Drug (1926) by AW Kapfer

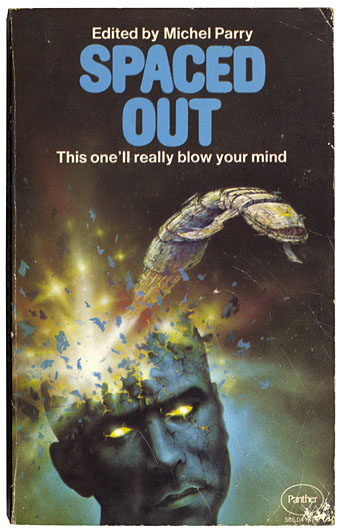

Cover art by Brian Froud.

Spaced Out (1977)

The Deep Fix (1964) by Michael Moorcock

All the Weed in the World (1961) by Fritz Leiber

The Roger Bacon Formula (1929) by Fletcher Pratt

Smoke of the Snake (1934) by Carl Jacobi

Melodramine (1965) by Henry Slesar

My Head’s in a Different Place, Now (1972) by Grania Davis

Sky (1971) by RA Lafferty

All of Them Were Empty— (1972) by David Gerrold

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Trip texts

• Acid albums

• Acid covers

• Lyrical Substance Deliberated

• The Art of Tripping, a documentary by Storm Thorgerson

• Enter the Void

• In the Land of Retinal Delights

• Haschisch Hallucinations by HE Gowers

• The art of LSD

• Hep cats