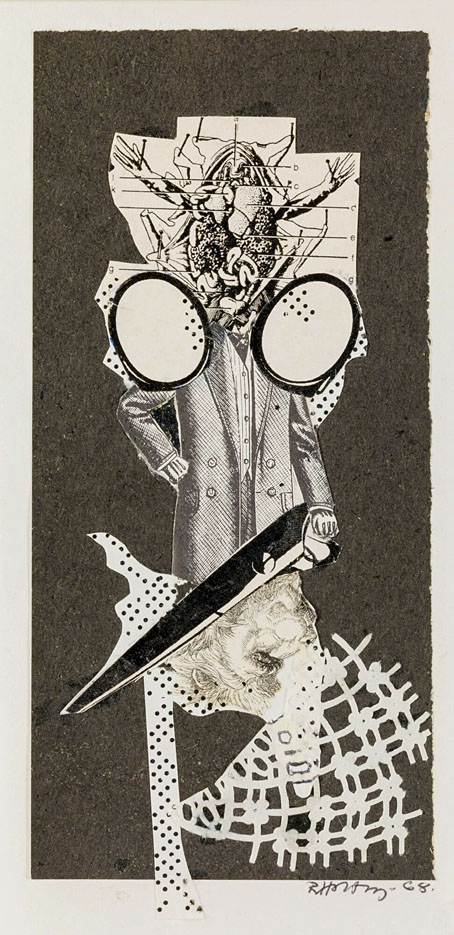

The Crystal World by JG Ballard. An illustration by Virgil Finlay for the Summer–August 1966 issue of Things To Come, the Science Fiction Book Club mailer.

1: Crystal words

JG Ballard didn’t have a pleasant experience with LSD when Michael Moorcock procured a dose of the drug for him in 1967, describing his acid trip in later years as a “psychotic nightmare”. I’ve often wondered how Ballard’s fiction might have developed in the 1970s if his experience had been a more positive one, something I was thinking about again when re-reading The Illuminated Man, a story collected in The Terminal Beach which was later reworked as The Crystal World, the fourth book in Ballard’s disaster quartet. There’s a psychedelic strain to Ballard’s writing which has long been overwhelmed by the popular enthusiasm for the condensed fictions of The Atrocity Exhibition and the three “concrete” novels of the 1970s: Crash, Concrete Island and High-Rise. The Crystal World was published in 1966 when LSD was still legally available in Britain, and even though the genesis of the book pre-dates the decade’s psychedelic fervour, the bejewelled prose chimes so well with the mood of the time it’s easy to assume it was inspired by psychedelic experience. Many readers thought as much, and in interviews Ballard had to emphasise that the novel was a product of his imagination and nothing more.

The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, May 1964. Cover art by Ed Emshwiller.

After devastating the planet with plausible disasters in his first three novels, Ballard in The Crystal World offers a distinctly fantastic scenario, in which an interstellar phenomenon (“the Hubble Effect”) is manifesting on Earth as the spontaneous crystallisation of all objects, animate or inanimate. The process begins in isolated areas before spreading worldwide; in keeping with many other Ballard stories from this period, time is responsible for the changes taking place:

Just as a supersaturated solution will discharge itself into a crystalline mass, so the supersaturation of matter in a continuum of depleted time leads to its appearance in a parallel spatial matrix. As more and more time “leaks” away, the process of supersaturation continues, the original atoms and molecules producing spatial replicas of themselves, substance without mass, in an attempt to increase their foothold upon existence.

The Illuminated Man

As with other Ballard stories, the scientific hand-waving is merely a pretext. In The Illuminated Man and The Crystal World “leaking time” provides an excuse to transform areas of Florida swamp and African jungle into glittering arcades of prismatic foliage, where birds are crystallised in mid-flight, reptiles transmute into heraldic emblems, and everything fluoresces with an iridescent radiance. The Illuminated Man is a sketch of the novel, with a different location but similar events, in which a hazardous mutating landscape becomes the stage for a small group characters pursuing each other and their own obsessions. Landscape is the important factor in The Drowned World, The Drought and The Crystal World; all three novels are essentially Surrealist landscapes whose reflections of interior states are the primary interest of the novelist, the narrative and the characters being very much secondary elements. In this respect it’s disappointing that The Crystal World has yet to be brought to life by an inspired illustrator, as we’ll see below. And while the novel may seem to be the least realistic of Ballard’s disasters it has a connection to future events. The Illuminated Man offers one of the first examples in science fiction (maybe the first) of an isolated zone which is being transformed by an extraterrestrial phenomenon, a concept usually credited to the Strugatsky Brothers in their novel Roadside Picnic (1972), and popularised by Andrei Tarkovsky in Stalker (1979). (Algis Budrys had done something similar in an earlier novel, Rogue Moon, but Budrys’s infected zone isn’t located on the Earth.) Tarkovsky’s film would subsequently provide the containment zone around the irradiated region of Pripyat in Ukraine with a template for unauthorised behaviour, where the illicit guides to the region took to describing themselves as “stalkers”. Until my re-read of The Illuminated Man I hadn’t registered Ballard’s reference to an additional outbreak of crystallisation occurring in the Pripet Marshes in what was then the Soviet Union, a vast region that includes the irradiated zone of Pripyat. The Soviet scientists attempt to deal with outbreak in their usual inefficient manner but for the world at large efficiency proves to be of little consequence either way; Ballard’s disasters aren’t problems to be solved, as they would have been for an earlier generation of writers. Global calamity is dealt with by gradual accommodation, and a reconfiguring of the human psyche which eventually comes to accept the altered landscape.

2: Crystal visions

Celestial Tree (1976) by Robert Venosa.

The most obvious psychedelic elements of The Crystal World are the novel’s emphasis on rainbow spectra and brilliant lights, the endless descriptions of prismatic diffractions and iridescence. But jewels and crystals are an important feature of psychedelic and visionary experience, a quality that Aldous Huxley explored at length in Heaven and Hell (1956):

Men have spent enormous amounts of time, energy and money on the finding, mining and cutting of coloured pebbles. Why? The utilitarian can offer no explanation for such fantastic behaviour. But as soon as we take into account the facts of visionary experience, everything becomes clear. In vision, men perceive a profusion of what Ezekiel calls “stones of fire,” of what Weir Mitchell describes as “transparent fruit.” These things are self-luminous, exhibit a preternatural brilliance of colour and possess a preternatural significance. The material objects which most nearly resemble these sources of visionary illumination are gem stones. To acquire such a stone is to acquire something whose preciousness is guaranteed by the fact that it exists in the Other World.

Hence man’s otherwise inexplicable passion for gems and hence his attribution to precious stones of therapeutic and magical virtue. The causal chain, I am convinced, begins in the psychological Other World of visionary experience, descends to earth and mounts again to the theological Other World of heaven. In this context the words of Socrates, in the Phaedo, take on a new significance. There exists, he tells us, an ideal world above and beyond the world of matter. “In this other earth the colours are much purer and much more brilliant than they are down here…. The very mountains, the very stones have a richer gloss, a lovelier transparency and intensity of hue. The precious stones of this lower world, our highly prized cornelians, jaspers, emeralds and all the rest, are but the tiny fragments of these stones above. In the other earth there is no stone but is precious and exceeds in beauty every gem of ours.”

In The Illuminated Man Ballard extends his own thoughts about precious stones to touch on the numinous:

Perhaps it is this gift of time which accounts for the eternal appeal of precious gems, as well as of all baroque painting and architecture? Their intricate crests and cartouches, occupying more than their own volume of space, so contain a greater ambient time, providing that unmistakable premonition of immortality sensed within St Peter’s or the palace at Nymphenburg. By contrast the architecture of the 20th century, characteristically one of rectangular unornamented facades, of simple Euclidean space and time, is that of the New World, confident of its firm footing in the future and indifferent to those pangs of mortality which haunt the mind of old Europe.

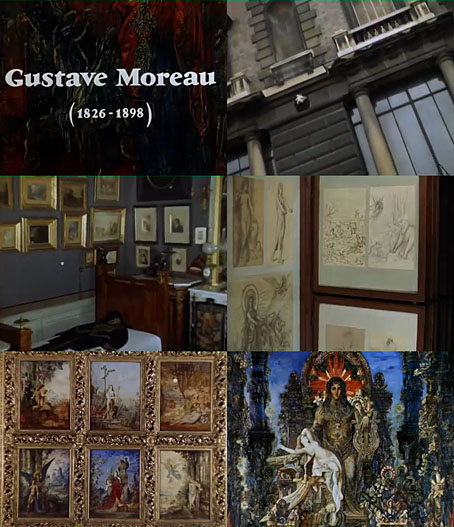

A moment of frozen time: Salome Dancing Before Herod (1876) by Gustave Moreau.

There’s an overt spirituality to The Illuminated Man and The Crystal World (both stories feature priests among their small cast of characters), which again seems psychedelic when placed in the context of crystalline transmutation, and which is diametrically opposed to the hard-edged materialism of the late novels. The second part of The Crystal World takes its title from the short story, with “illuminated” here referring to a process of psychological (or even spiritual) illumination in addition to the more obvious generation of light.

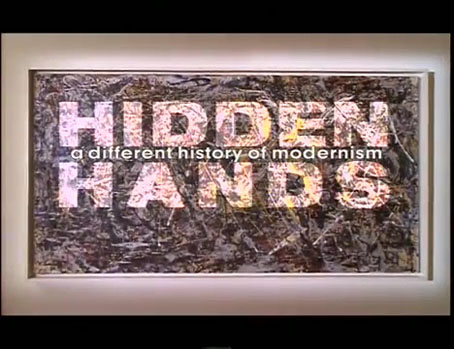

A late manifestation of the Symbolist Ballard, 1982. Cover art by Bill Botten.

I think of this side of Ballard’s work as less religious than Symbolist, an expression of his enthusiasm for Symbolist art and artists; the opening chapter of The Crystal World has the priest with an artist’s surname, Father Balthus, comparing the gloomy light around Port Matarre to the impending storm in Arnold Böcklin’s Isle of the Dead. The painting chosen to wrap the covers of the first edition of The Crystal World was The Eye of Silence by Max Ernst, a choice almost certainly suggested by Ballard himself who included the same picture in a list of favourite Surrealist paintings for New Worlds. The painting is the closest that Ernst gets to the jewelled settings of Gustave Moreau, an artist whose Byzantine architectures are studded with precious stones.

The Symbolist Ballard surfaced in occasional short stories throughout the late 60s and the concrete 70s but didn’t return in full until 1979 with the publication of The Unlimited Dream Company. The novel is such a dramatic break with the concrete novels it suggests a sudden release of pressure, as the Symbolist Ballard erupts into life with another story about the wholesale transformation of a circumscribed zone. The locus this time is Ballard’s home territory of Shepperton which is turned into a tropical paradise by the arrival of a wounded pilot (significantly named Blake) whose small plane has crashed into the River Thames. Blake may be suffering from brain damage, he may be imagining all the novel’s events in the moments before his death, or he may even be a new messiah; as with The Crystal World, the explanation is a side issue, the author is more interested in the transformed environment and its effect on the inhabitants of the town.