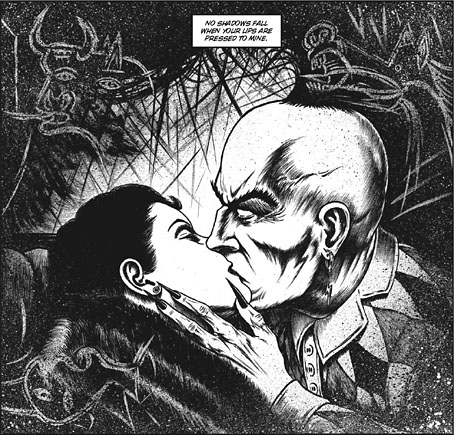

Keith Seward’s Horror Panegyric was a concise examination of David Britton’s multimedia Lord Horror project which Savoy Books published in 2007. I designed the book, the cover of which was my Arcimboldo pastiche of Lord Horror’s profile which appeared on the cover of issue 3 of Reverbstorm. The Supervert site which hosts an online copy of Horror Panegyric has this month posted my answers to some questions about Reverbstorm, the series having grown out of the first Lord Horror novel and the earlier comics:

The graphics in Reverbstorm sometimes seem more narrative than the words. How did you and David work out a scenario?

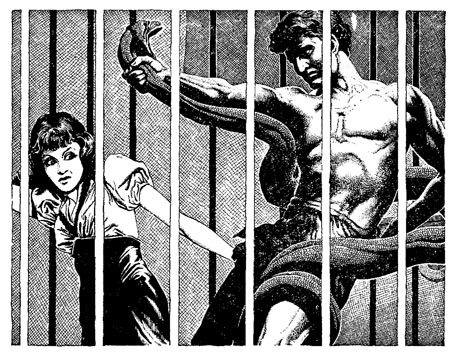

I don’t have objections per se to the usual story structures but in this series we both wanted to create something that wasn’t following familiar adventure narrative lines. The precedents for me were the European comic artists from Métal Hurlant who often favoured art over story; also Burne Hogarth whose work was a great influence on the style I used to draw Lord Horror. Hogarth’s Tarzan strips are adventure narratives but in his later books it’s the art that’s paramount. James Joyce is one of the characters in Reverbstorm, and you can also find a precedent in Ulysses where the story is overwhelmed by the surface detail.

Reverbstorm began with Paul Temple’s lyrics for the Reverbstorm song and a brief Lord Horror film treatment that Dave and Mike had put together for a production company. I don’t recall much about the treatment — I only looked at it once in the office — but it concerned Horror and Jessie Matthews in New York City, opening with a sequence where his Lordship kills some policemen in an alleyway. That vague outline can be seen in the first few pages of Reverbstorm with NYC changed to Torenbürgen. Other elements taken from the film treatment included the name Blue Blaze Laudanum — the actual robotic character came later — and the Souls which likewise became more substantially developed as the comic progressed.

Once we’d introduced all the characters things developed along thematic lines rather than strictly narrative ones. So the second part introduces the Ether Jumpers, the third part has the Apes, the fourth part the Ononoes, the fifth part Picasso and T.S. Eliot, and so on. Musical structure is an obvious parallel, and I consider some of the recurring background material to be visual leifmotifs which can indicate or imply one of the three main characters even if they aren’t present on the page. This musical analogy is an important one for appreciating the series as a whole. The entwined themes and references work in a manner that’s a lot closer to musical works than to the mechanics of an adventure narrative. (more)

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Reverbstorm in print

• Reverbstorm update

• James Joyce in Reverbstorm

• A Reverbstorm jukebox

• Reverbstorm: Bauhaus Horror

• Reverbstorm: an introduction and preview