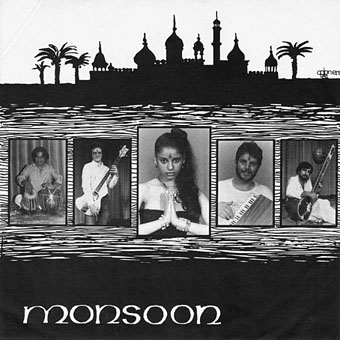

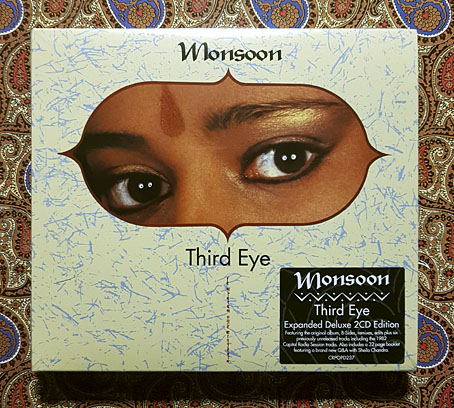

You know an album is a cult item when you find yourself buying it for the fourth time. I’ve owned Third Eye in most of its previous incarnations—original vinyl, UK CD, US CD with bonus tracks—but this latest reissue from Cherry Red is the first to summarise the career of the group that recorded it. Monsoon were an Anglo-Indian pop ensemble who released just one album and a handful of singles in the early 1980s before disbanding:

Monsoon led by singer Sheila Chandra (best known for her role in the BBC’S Grange Hill) along with record producer Steve Coe and bass guitarist Martin Smith was a brave and pioneering pop trio that blended traditional music from the Indian sub-continent with 80s British pop. Additionally, they drew on the best musicians they could find from both East and West.

The band originated in 1980 when keyboard player and producer Steve Coe developed an interest in Indian music. Hoping to form a band to pursue this direction, he discovered Sheila via some demo tapes which she had recorded for Hansa Records when she was 14. Sheila joined Monsoon in March 1981, three months before she left school. Monsoon’s first EP Ever So Lonely/Sunset Over The Ganges/Mirror Of Your Mind/Shout Till You’re Heard had been distributed by Rough Trade. Their fresh Asian Fusion sound attracted the attention of label owner David Claridge, and Phonogram A&R man Dave Bates who signed the outfit to the Mobile Suit Corporation (Phonogram).

In December 1981, the band re-arranged and re-recorded Ever So Lonely at Rockfield Studios with co-producer Hugh Jones, released by Mobile Suit Corporation (Phonogram) in 1982 and, though surrounded by synth-pop singles, and predating the term “World Music” by a full five years, was a smash hit around the world, reaching No.12 in the UK singles chart.

Two further singles followed; Shakti (The Meaning Of Within) and a cover of The Beatles’ Tomorrow Never Knows along with the debut album Third Eye but due to differences with their label, Phonogram, Monsoon dissolved later in 1982.

John Peel apparently played Ever So Lonely on his late-night radio show but I missed it there, hearing it for the first time on the Radio 1 chart countdown one Sunday afternoon. Surrounded by synth-pop hits, the song was strikingly exceptional, while the album that followed still sounds out of time, an infectious blend of sitar, tabla, pop hooks, the occasional drum machine and Bill Nelson’s E-bow guitar. The group’s cover of Tomorrow Never Knows gestures towards the sitar’s entanglement with the psychedelic 60s although you can’t read too much into this when it was Phonogram executives who insisted on a Beatles song. If you’ve never heard this version you may suspect Monsoon of creating a novelty confection like those that fill Sitar Beat (1967), Big Jim Sullivan’s collection of Indian-flavoured psychedelic pop. Monsoon’s cover is much better than Sullivan’s instrumentals, an arrangement that sits so easily among the rest of the songs on Third Eye that it sounds like something they might have written themselves.

One of several Indipop compilations.

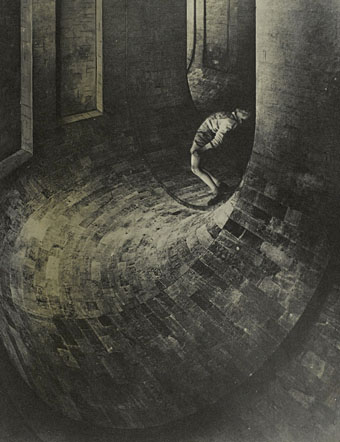

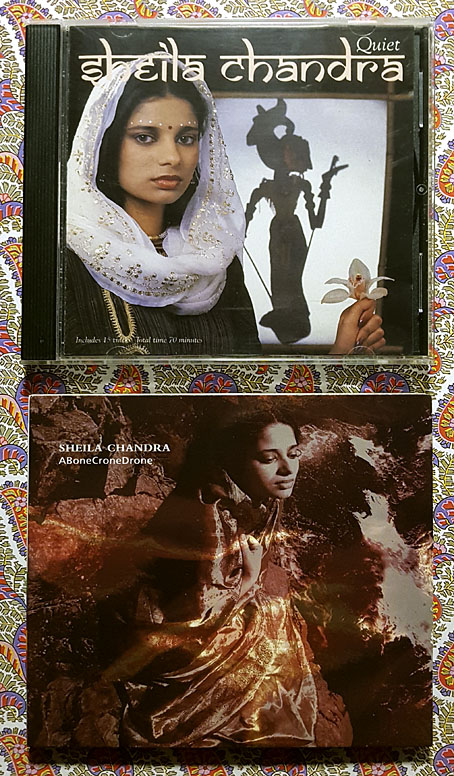

Monsoon didn’t last long but this was only the beginning for Sheila Chandra and Steve Coe who combined forces by getting married and following new musical directions with Coe’s Indipop record label. Indipop developed Monsoon’s fusion sound in a variety of guises centred around Sheila Chandra’s solo releases and The Ganges Orchestra, a Steve Coe studio creation. The label also established links with artists pursuing similar ends, groups like Manchester’s Suns of Arqa, and West India Company, a Blancmange spin-off who brought Asha Bhosle’s voice to European dancefloors. Some of Sheila Chandra’s early albums are a little uneven compared to Third Eye but the best of them, especially Quiet! (1984) and Nada Brahma (1985) are highly recommended. The expanded CD release of Quiet! is another cult disc of mine, a near-beatless suite of raga-like vocalisations. Quiet! foreshadows the paring back of instrumentation that took place on Chandra’s subsequent albums for the Real World label, one of which, Weaving My Ancestors’ Voices (1992) featured an a cappella reprise of Ever So Lonely a decade after the song had reached the Top Twenty. Four years after this, the writers at The Wire magazine voted her third Real World release, ABoneCroneDrone, one of their albums of the year. An interview in the same magazine showed how far Sheila Chandra had travelled in her evolution as a singer and musical artist, from the Top of the Pops studio to this:

The initial recordings for ABoneCroneDrone were made in a deconsecrated church in Bristol: tamburas, harmoniums and vocal tracks were laquered on top of one another, and her voice was also played into the body of a piano via a speaker underneath, to get the strings resonating. Further devices were added to bring character to different tracks, such as didgeridoos, bagpipes, ocean swells and birdsong.

“There was a very fine line to draw between how loud the vocals should be, so that people who weren’t tuned into harmonics could actually hear the subtle things going on, and how far we were drowning out natural harmonics that occurred. And the other kind of balance to be reached was that when I hear a drone as it’s played, unmagnified, untreated, and I hear all these harmonic dances in it and then play it five minutes later, I’ll hear a different dance. I’ll hear South Indian carnatic violins, I’ll even hear rhythm. This performance is going on, and I’ll hear it clear as a bell, very quietly, and it’s in this drone. So, to freeze what I was hearing magnified was also a dilemma, because I didn’t want to make it a static, dead experience. So what we’ve done is layer so many things that you’ll only hear some on different systems and some at different volumes or in different acoustic spaces. There are some things you’ll only hear on the twelfth listen. And it’s like a living experience then.”

Essential listening.

The only drones on Third Eye are the resonating strings of the Indian instruments, but this is a pop album, after all, not an avant-garde composition. The new reissue is a 34-track double-disc set that contains enough versions of Ever So Lonely to satisfy the most ardent fan, including the Hindi version and a dub mix. In addition to the original album you get all the other singles with their B-sides, a handful of later remixes and six previously unreleased songs, four of which are sessions recorded for Capital Radio in March 1982.

This would be pretty much definitive if it wasn’t for one of those inexplicable alterations that often bedevil reissues. The final track on the album, Watchers Of The Night, is missing ten seconds or so of the drum-machine intro that you hear on the earlier CD releases. I no longer have my vinyl copy but I’m fairly sure this was the same; Discogs gives the original vinyl duration as 3:47, whereas the new reissue runs for 3:38. Anomalies aside, the mastering is much better than before, something that really benefits the bass and the percussive details. The album has been unavailable in any form since 1995 so this attention is long overdue. Now that Cherry Red have found their way to Indipop’s neglected archives I’m hoping further reissues may follow.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Ravi Shankar’s metempsychosis

• Tomorrow Never Knows