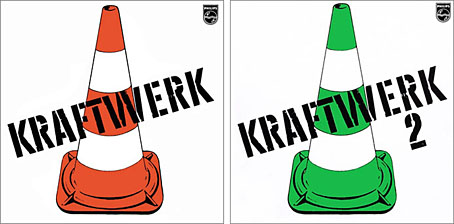

Kraftwerk (1970); Kraftwerk 2 (1972). Design by Ralf Hütter.

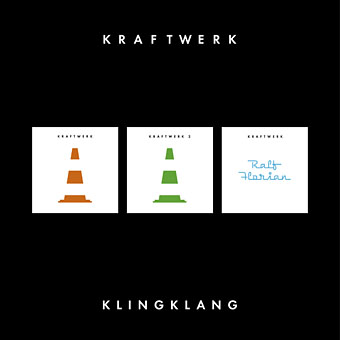

Recent posts about Kraftwerk’s design history had me wondering how the group might present the first three albums if these repudiated works were allowed back into the catalogue. Kraftwerk, Kraftwerk 2, and Ralf and Florian haven’t been officially reissued for decades now, and I remain sceptical that Ralf Hütter (or the recently departed Florian Schneider) are willing to taint their carefully cultivated discography with those awkward, experimental albums. This is highly unusual in the music world where everything by a commercially successful group tends to be reissued on a regular basis.

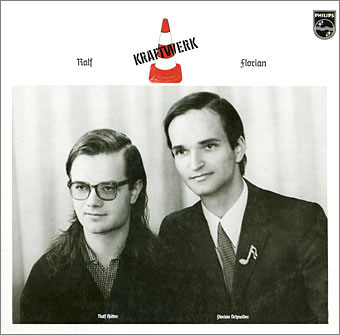

Ralf and Florian (1973). Design by Ralf Hütter & Florian Schneider. Photo by Robert Franck.

Kraftwerk are unique in this, and also in subjecting their approved releases to incremental adjustments. This was mostly strikingly seen in 2009 when the 8 albums were reissued in a box as The Catalogue. Not only had further changes been made to the cover art but two of the albums had amended titles: Electric Café was now Techno Pop (as it would have been titled if released earlier in the 1980s), and Tour De France Soundtracks had become Tour De France. The cover art changes had already been previewed in the version of The Catalogue that briefly appeared as a promo set in 2004 only now it was evident that more human traces were being removed from the albums, notably on the cover of The Man-Machine which swapped the band photo for the El Lissitzky-derived graphics. All of this needed to be taken into account when I had the idea last week of roughing out designs for how the first three albums might be reissued in a box set today.

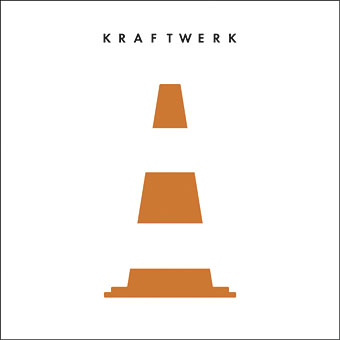

First the title: there’s no way of knowing what Ralf Hütter might call a collected set but mundane choices like Three Albums or Kraftwerk 70–73 seem unlikely. I decided on Klingklang, the name of the first piece of music on the second album, and also the name of Kraftwerk’s studio and publishing company. This would no doubt cause endless (endless) confusion but it still seems apt. The cover design uses Futura, a German typeface that’s been a feature of many Kraftwerk graphics over the years. The oscilloscope wave is taken from the front and back cover of the double-album reissue of Kraftwerk and Kraftwerk 2 on the Vertigo label in 1972. I always liked that cover, and the graphic suits the often raw electronic sound of those albums as well as the minimal nature of the current design.

This would be the back of the proposed box, showing the albums within as The Catalogue does.

All German traffic cones still follow this standard, apparently, so the design hasn’t dated at all. (See this post for Kraftwerk’s cone obsession.) Using negative space for the white bands works well.