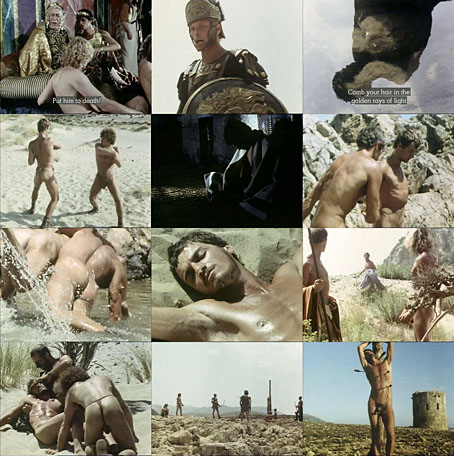

Sebastiane Opens

October 1976: Sebastiane opened at the Gate cinema in Notting Hill last night after a day of record attendances and good reviews. At the opening Barney James, who plays the centurion, sat next to my parents. At the end of the film he turned to Dad and said, “I don’t suppose forces life was ever like that.” To my surprise Dad replied, “I was out in the Middle East before the war and it’s really quite accurate.”After its opening at the Gate, where it played for four months before moving into the West End, Sebastiane opened all over the world to wildly different reviews. The Germans found our Latin untuned to their ears, and the French, at least so I was told, panned it. In the States it was classed S for Sex and we were unable to advertise it – so the audiences turned up expecting hardcore and were disappointed. However in Italy and Spain it was a stunning success with lyrical reviews. In Rome, Alberto Moravia came to the first press show and praised the film in the foyer saying that it was a film that Pier Paolo would have loved.

Derek Jarman, Dancing Ledge (1991)

Pasolini would indeed have loved Sebastiane (1976) which owes much to the Italian director’s historical films, especially Oedipus Rex (1967) and Medea (1969). The film was Jarman’s first feature (co-directed with Paul Humfress), produced on a very small budget, and filmed on the coast of Sardinia. Brian Eno provided the music, and Lindsay Kemp has a memorable cameo appearance in the opening scene. The events which lead to the martyrdom of Saint Sebastian (Sebastianus) are dramatised from the point of view of a group of Roman soldiers who have Sebastianus among their company. The film is notable for its all-Latin dialogue, and for being the first non-porn film to feature a male erection, although that detail is often missing from prints which judiciously crop the lower portion of the screen.

The copy linked here has somehow turned up at the Internet Archive, and is the same erection-free version which has circulated for some years on DVD. The sneaky censorship would have been justified ten or more years ago but makes no sense today when far more explicit films are easily available. But if you haven’t seen Sebastiane then you have an opportunity for as long as this copy remains available…which may not be for long since I’m sure its copyright can’t have lapsed.

The late, unlamented and very reactionary British film critic Leslie Halliwell once complained that Pasolini’s “Trilogy of Life” films featured “a forest of male genitalia”. The same might be said of Sebastiane which, judging by the intemperate comments one sees on review sites, provokes a similar splenetic reaction. “It’s just gay porn!” they shriek, to which the obvious response is “No, it isn’t”, and “So what if it was?” A century of cinema has paraded the bodies of women for the gaze of the heterosexual male, the same male who chokes on his dudgeon when faced with the very thing he carries between his legs. Grow up, boys. Also at the Internet Archive (for the time being) is Derek Jarman’s The Garden (1990), the most personal of his later films until his final feature, Blue, in 1993.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• A Journey to Avebury by Derek Jarman

• Derek Jarman’s music videos

• Derek Jarman’s Neutron

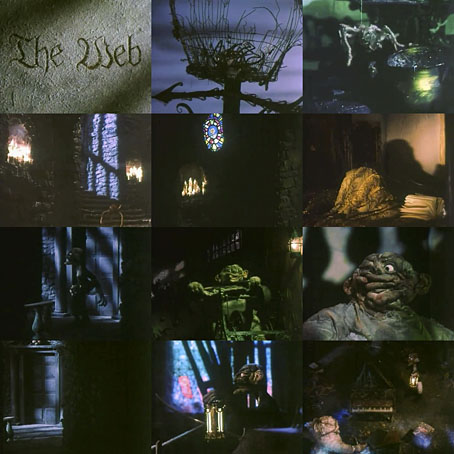

• Mister Jarman, Mister Moore and Doctor Dee

• The Tempest illustrated

• In the Shadow of the Sun by Derek Jarman

• Derek Jarman at the Serpentine

• The Angelic Conversation

• The life and work of Derek Jarman