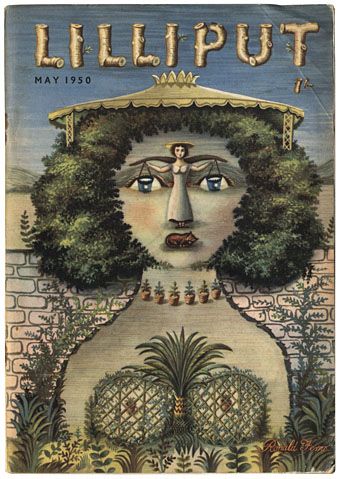

This month I’ve been redesigning the Savoy Books edition of The Exploits of Engelbrecht by Maurice Richardson, in preparation for a reprint. This has involved scanning the covers of the issues of Lilliput, the magazine where Richardson’s tales of the dwarf surrealist sportsman first appeared, and one number of these, from May 1950, also includes a feature about nursery rhymes illustrated by Mervyn Peake. The paintings were reprinted in Mervyn Peake: The Man and his Art in 2006 but shrunk onto a single page so this is a chance to see them at a larger size. Also reproduced below is the accompanying article by Leslie Daiken and the Arcimboldo-style cover by Ronald Ferris. Some of the earlier covers by Walter Trier—all of which featured a man, a woman and a dog in a variety of guises—can be seen at VTS.

Update: For more about Mervyn Peake, see also Peake Studies.

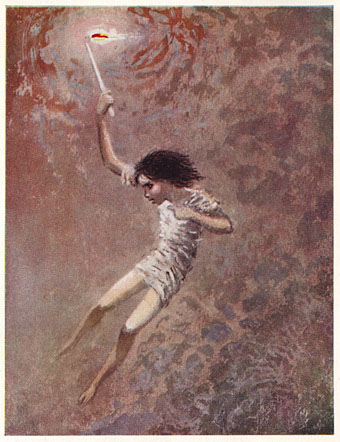

“How many miles to Babylon?”

“Three score miles and ten.”

“Can I get there by candle-light?”

“Yes, and back again.

If your heels are nimble and light

You may get there by candle-light.”

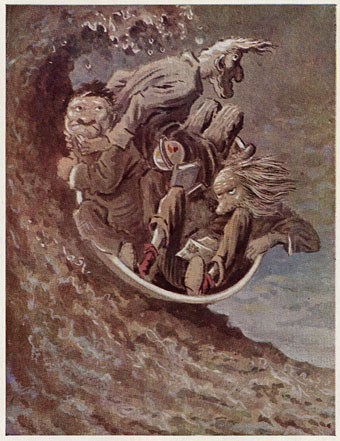

Three wise men of Gotham

Went to Sea in a Bowl.

If the Bowl had been stronger,

My tale had been longer.

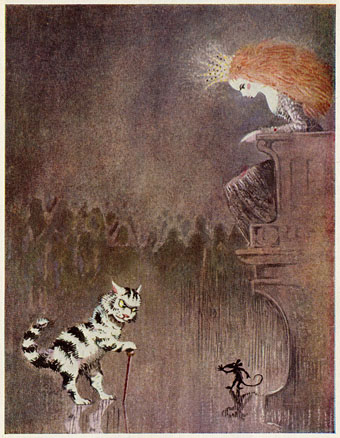

“Pussy cat, Pussy cat, where have you been?”

“I’ve been to London to visit the Queen.”

“Pussy cat, Pussy cat, what did you there?”

“I caught a little mouse under the chair.”

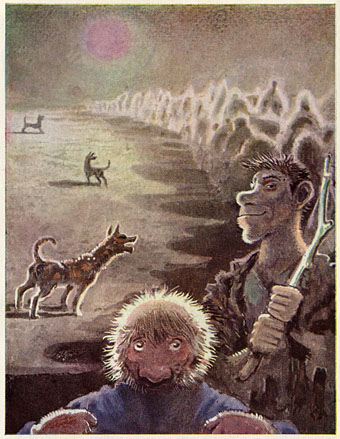

Hark! Hark! The dogs do bark,

The beggars are coming to town.

Some in rags and some in tags,

And some in silken gown.

Some gave them white bread,

And some gave them brown,

And some gave them a good horse-whip,

And sent them out of town.

Lilliput, vol. 26, no. 5; issue no. 155; cover by Ronald Ferris.

Children’s Hour

Four Nursery Rhymes. Illustrated by Mervyn Peake

With a Commentary by Leslie Daiken

IN 1837 a Mr. John B. Ker published a large volume, annotated up to the hilt, to prove that nursery rhymes were cryptic slogans against corruption in the Church.

Since then, countless other experts—ethnologists, philologists, musicologists, historians and preachers—have followed in his footsteps, and come to widely divergent conclusions of their own.

They have had a fertile field in which to work, for nursery lore contains something like 6oo-odd snippets, which can be said to pass for rhymes. Yet only a fraction of them are true children’s doggerel. The rest stem from a grown-ups’ world-shreds of rural malice, old folk-fancies, libellous lampoons, political satire grown blunt, miniatures of history, or lullabies devised by harassed mothers.

These four nursery rhymes, illustrated by Mervyn Peake, have as complex a background as any.

The first one—’How many miles to Babylon?’—is cast in the mould of a parley between travellers and the Gate Keeper of some ancient walled city. This, no doubt, will come as a surprise even to the brightest child.

The parley was used as a rhyme accompaniment to a game similar to ‘Oranges and Lemons,’ but what walled cities have to do with oranges or lemons has never been revealed. It may be accepted, however, that Babylon, in the nursery, represents the most remote of remote and mysterious places. In some nurseries it has become corrupted to ‘Babyland,’ while in Belfast it is known as ‘Sandy Row’!

Where Babylon stands for a land of fantasy, Gotham is the town of fools. Early in the 16th century a Dr. Andrew Borde wrote some disagreeable stories about the Fools of Gotham; the rhyme about the three wise men in the bowl perpetuates their foolishness. There is a village near Leicester called Gotham, but this seems to be merely an unfortunate coincidence.

The queen visited by the cat in the third picture is popularly supposed to have been Good Queen Bess. But the rhyme, ‘Pussy-cat, pussy-cat, where have you been…’ did not appear in print until 1805. It seems strange that the cat found no more immediate biographer, after having taken the trouble to walk all the way to London to see the Queen. Some doubt must be cast upon Elizabeth’s part in the matter.

With the last picture, ‘Hark, hark, the dogs do bark…’, we seem to be on firmer ground, in possession of no less than two reasonable explanations of why the dogs did bark, and the beggars came to town.

Iona and Peter Opie, two inexhaustible researchers into the origins of nursery rhymes, maintain that this was a parody of a political song printed in 1672. Can it be a dig at William of Orange, and Mary, his Queen, who arrived in England round about this time attended by a horde of singularly impecunious followers?

Some in rags and some in tags,

And some in a silken gown.

The fact that the song was written several years before William and Mary arrived in England can be explained by the theory that the writer had previously been to Holland, and, having seen the Dutch court, knew what to expect.

The other explanation has been provided by a Mr. A. B. Haigh. He provides a summary of social upheaval in the reign of Henry VIII.

“Britain,” he says, “had turned over from arable to pastoral farming. Land workers wandering round the country were joined by manservants from the big feudal households, which had been broken up by Henry’s Statute of Livery and Maintenance. The influx of these men without a trade worried towns-people.”

Some gave them white bread,

And some gave them brown,

And some gave them a good horse-whip,

And sent them out of town.

It is to be regretted, of course, that one nursery rhyme should have two such convincing, but diametrically opposed, explanations, since it leaves us in almost as great a state of uncertainty as before. But we have the comfort of knowing that there is always ‘Ring-a-ring-a-roses,’ the one nursery rhyme with a really solid historical background.

‘Ring-a-ring-a-roses’ is a song of the Great Plague. Here, everything fits beautifully into place.

The ring of roses are the plague spots. A pocketful of posies refers to the sachets of herbs that people carried in the hope that the herbs would lend them immunity to the disease. And, ‘Atishoo-atishoo-we all fall down!’ is what happened when people found that the herbs didn’t.

It might, at first sight, seem strange that so many little children, in these days, should derive so much innocent pleasure from gambolling about hand in hand singing cheerfully of a pestilence that swept their ancestors away by the hundred thousand; but then we must remember that we are dealing with the nursery rhyme.

In the nursery rhyme there may be rhyme, but there certainly is never any reason.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The illustrators archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Illustrators of Alice

Thanks so much for these. I really need to dig further into your archives!

I also can’t wait to read the “tales of the dwarf surrealist sportsman.”

Thanks Will. And Engelbrecht is a fantastic book. Also happens to be one of JG Ballard’s favourite books, he supplied Savoy with a blurb about it.