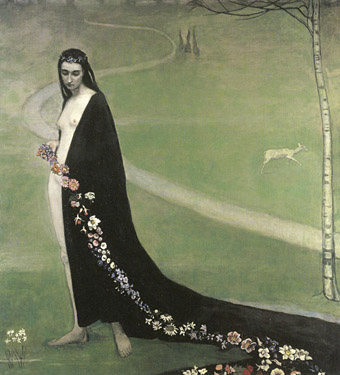

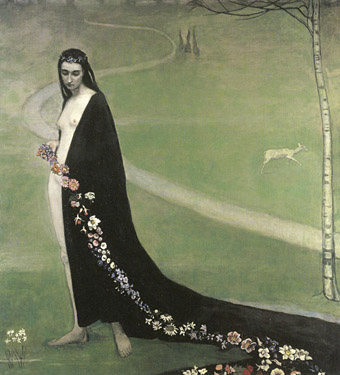

Femme avec des fleurs (c. 1912) by Romaine Brooks.

• “Boring people tend not to exile themselves to rocky islands, but even among the intriguing personalities we encounter in Capri, some individuals prove more extravagantly memorable than others.” Steve Susoyev reviews Pagan Light: Dreams of Freedom and Beauty in Capri by Jamie James.

• “The Mad “idiots” subverted the comic form into a mainstream ideological weapon, aimed at icons of the left and the right—attacking both McCarthyism and the Beat Generation, Nixon and Kennedy, Hollywood and Madison Avenue.” Jordan Orlando on a world without Mad Magazine.

• RIP Sam Gafford, Paul Krassner and Rutger Hauer. Related to the latter: Hauer’s first role as Floris, the hero of a Dutch TV series directed by Paul Verhoeven.

I cannot tell you what it does to me to hear pre-Stonewall. And even in our literature, even in the art, pre-Stonewall, post-Stonewall. I wrote three books pre-Stonewall and a dozen more post-Stonewall. There’s no demarcation. Gay history is centuries and centuries from the Romans to the Greeks to Oscar Wilde to all kinds of outrages. And those seem to be put back and pre-Stonewall is passive. Post-Stonewall is brave and dignified. I actually have heard things like that. I’ve talked, I’ve lectured and I’ve been invited all the way from Harvard to USC. And I talk about what it was like, what we had to survive.

Look, pre-Stonewall produced Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, Oscar Wilde, and I could go on. Post-Stonewall produced Bret Easton Ellis, who jumps out of the closet only now and then and then rushes back in, and Queer Eye for the Straight Guy, where we’re reduced to clowns for straight people. The husband of Mr. Buttigieg, he is so darling talking about the silver he’s going to be choosing for the White House. It embarrasses me, it embarrasses me very much because that’s what people expect a gay man to do, to be very precious, and that’s not what we are. A good solid queen I will protect forever, they are heroes.

A lot of people think that everything stopped, everything, all harassment stopped. Look, it’s still going on. It’s still going on, for god’s sake. The same tactics are often used in a different way.

John Rechy talking to Jason McGahan

• The genius of Barry Adamson: An exclusive interview by Paul Gallagher at Dangerous Minds.

• Three hours of the Prophecy Theme from Dune (by Brian Eno with Daniel Lanois & Roger Eno).

• Ed Sanders on why pop culture still can’t get enough of Charles Manson.

• Havelock Ellis takes a trip: Mike Jay on peyote among the Aesthetes.

• Darren Anderson on why little works of architecture deserve respect.

• Mix of the week: Stephen O’Malley presents / Java / Apr 27 2017.

• Phil Hine reviews Folk Horror Revival: Urban Wyrd 1 & 2.

• John Waters revisits “The Golden Age of Monkey Art”.

• I Must Be Mad (1966) by The Craig | The Day My Pad Went Mad (1982) by John Cooper Clarke | Yesterday, When I Was Mad (1993) by Pet Shop Boys