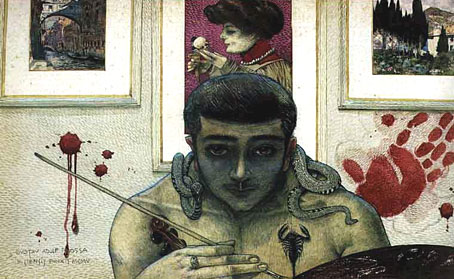

Monsieur Jullian as seen on the back cover of Dreamers of Decadence (1971).

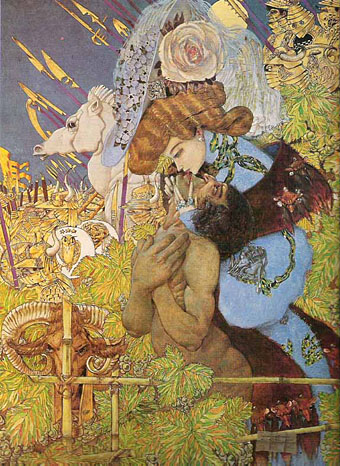

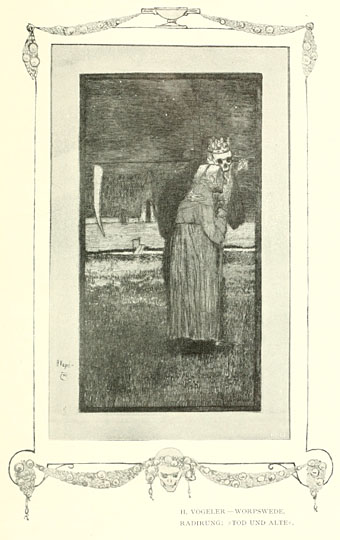

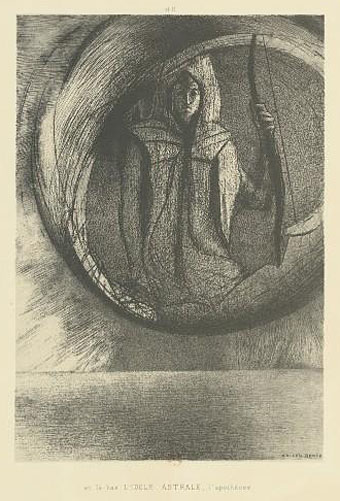

Here at last is the long-promised (and long!) piece about the life and work of Philippe Jullian (1919–1977), a French writer and illustrator who’s become something of a cult figure of mine in recent years. Why the fascination? First and foremost because at the end of the 1960s he wrote Esthètes et Magiciens, or Dreamers of Decadence as it’s known to English readers, a book which effectively launched the Symbolist art revival and which remains the best introduction to Symbolist art and the aesthetic hothouse that was the 1890s. If I had to choose five favourite books Dreamers of Decadence would always be on the list. This point of obsession, and Philip Core’s account of the writer, made me curious about the rest of Jullian’s career.

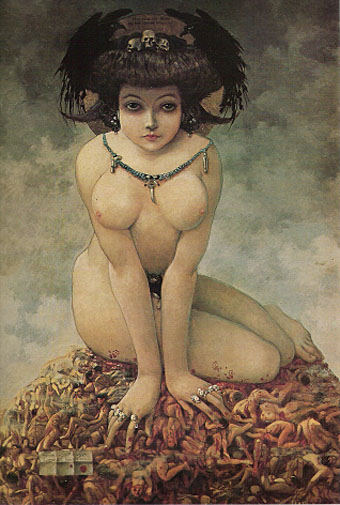

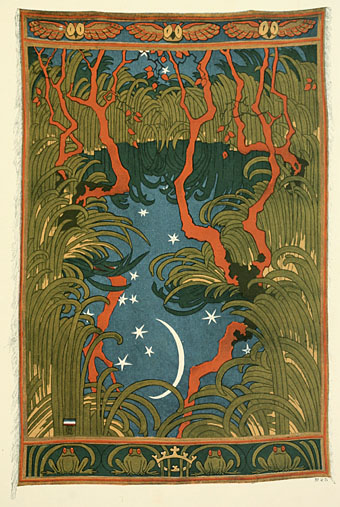

An illustration from Wilson & Jullian’s For Whom the Cloche Tolls (1953). “Tata has called these his Krafft-Ebbing (sic) pictures of his friend Kuno, whatever that means.”

Philip Core was friends with Philippe Jullian, and Core’s essential Camp: The Lie that Tells the Truth (1984) has Jullian as one of its dedicatees. It’s to Core’s appraisal that we have to turn for details of the man’s life. There is an autobiography, La Brocante (1975), but, like a number of other Jullian works, this doesn’t seem to have been translated and my French is dismally pauvre. Core’s piece begins:

Philippe Jullian, born to the intellectual family of Bordeaux Protestants which produced the well-known French historian, Camille Jullian, was a last and lasting example of pre-war camp. His career began as an artist in Paris with a reputation for drag-acts parodying English spinsters. Snobbery, a talent for sensitive daydreaming, and a consuming passion for antiques, obscure art and social history, made a very different figure out of the thin and dreamy young man. Jullian suffered terribly during the Second World War; he managed to survive by visiting some disapproving cousins dressed as a maiden aunt, whom they were happy to feed. However, he made a mark in the world of Violet Trefusis, Natalie Barney and Vita Sackville-West by illustrating their books with his wiry and delicate doodles; this led to a social connection in England, where he produced many book jackets and covers for Vogue throughout the 1950s.

Having only seen Jullian in his besuited and bespectacled guise it’s difficult to imagine him dragged up, but the cross-dressing interest is apparent in his humorous collaboration with Angus Wilson and in a later novel, Flight into Egypt. As for the wiry and delicate doodles, they’re very much of their time, in style often resembling a less-assured Ronald Searle. One early commission in 1945 was for the first of what would become a celebrated series of artist labels for Château Mouton Rothschild. Later cover illustrations included a run for Penguin Books some of which can be found at Flickr.

Philip Core continues the story:

Elegant in the austerely tweedy way the French imagine to be English, Jullian exploited his very considerable talents as a writer, producing a series of camp novels throughout the 1950s (Scraps, Milord) which deal frankly but amusingly with the vicissitudes of handsome young men and face-lifted ladies, grey-haired antique dealers and criminals. One of the first to reconsider Symbolist painting, Jullian reached an enormous public in the 1960s with his gorgeous book, Dreamers of Decadence – where an encyclopaedic knowledge of the genre and its accompanying literature helped to create the boom in fin de siècle revivalism among dealers and museums.

An acerbic wit accompanied this vast worldly success; always docile to duchesses, Jullian could easily remark to a hostess who offered him a chocolate and cream pudding called Nègre en chemise, “I prefer them without.” Less kindly, to a gay friend who objected to Jullian’s poodles accompanying them into a country food shop by saying “Think where their noses have been”, he could also retort “Yes, that’s what I think whenever I see you kiss your mother.”

Continue reading “Philippe Jullian, connoisseur of the exotic”