Struggle (2009) by Lindsey Carr.

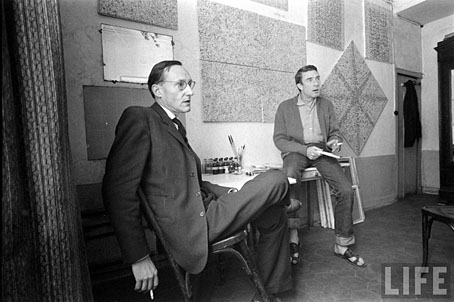

• “Twilight Science is an imprint for sound, music and DVD editions initiated by artist Paul Schütze. We will progressively publish all back catalogue, new projects and collaborations. These will include works by Phantom City, NAPE, Schütze-Hopkins and others.” Related (because Paul Schütze remixed Main): Main Feed The Collapse, Neil Kulkarni talks to Robert Hampson.

• “You can’t really narrate or display this situation, you can only, endlessly, contemplate it. When the writer or director gets tired of the iterations, he tells us who the mole is.” Michael Wood on the novel, (superb) television series and recent film of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy.

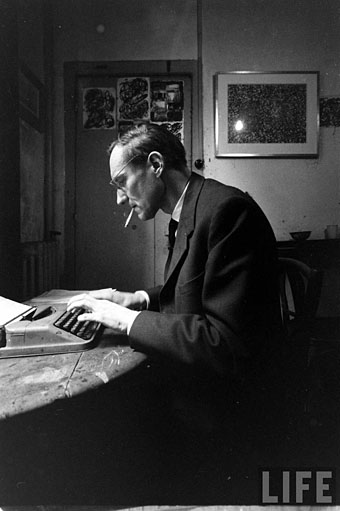

• “Havin’ a dick is pretty fuckin’ awesome” says Horst, a new gay magazine limited to 1000 copies. Related (well, there’s a guy in and out of his underwear): Naked Lunch, a fashion shoot very tenuously based on David Cronenberg’s film.

“At first, I tried fighting bullies one-on-one, but they don’t fight fair; they fight two and three on one,” Bennett said. So the youths got together and “started carrying mace, knives, brass knuckles and stun guns, and if somebody messed with one of us then all of us would gang up on them.”

“Gay black youths go from attacked to attackers” says the headline. A group of genuine Wild Boys; William Burroughs would have approved.

• Tor.com reminded me of Sally Cruikshank‘s amazing animated film Face Like a Frog (1987) which features a score and Cab Calloway-style song by Danny Elfman.

• It’s 1969, OK? Pádraig Ó Méalóid talks with Kevin O’Neill about the Swinging League of Extraordinary Gentlemen.

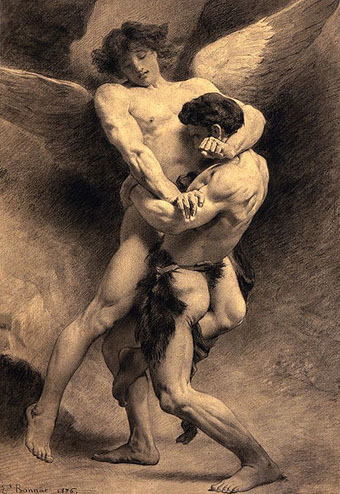

• In the Tumblr labyrinth this week: Fuck Yeah St Sebastian and Gender is Irrelevant.

• For when you need some motherfucking placeholder text: Samuel L Ipsum.

• “Study finds ‘magic mushrooms’ may improve personality long-term.”

• Solar Megalomania: paintings by Leonora Carrington.

• It’s all fun and games until Charles Manson turns up.

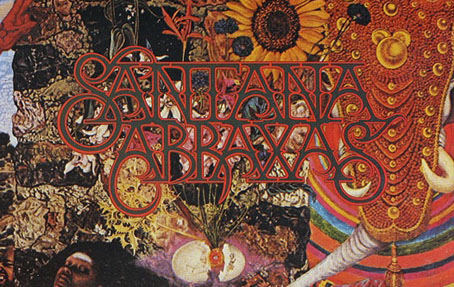

• Firmament II (1993) by Main | Firmament IV (1993) by Main | Reformation (1994) by Main.