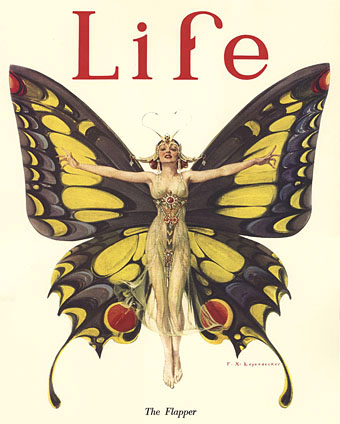

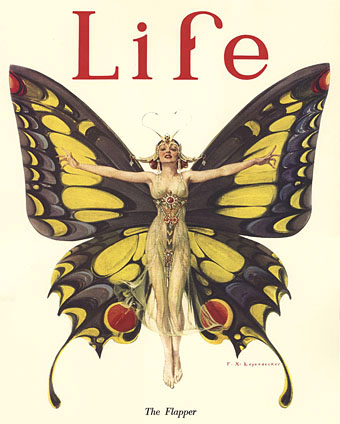

The Flapper by Frank X Leyendecker, Life magazine (1922).

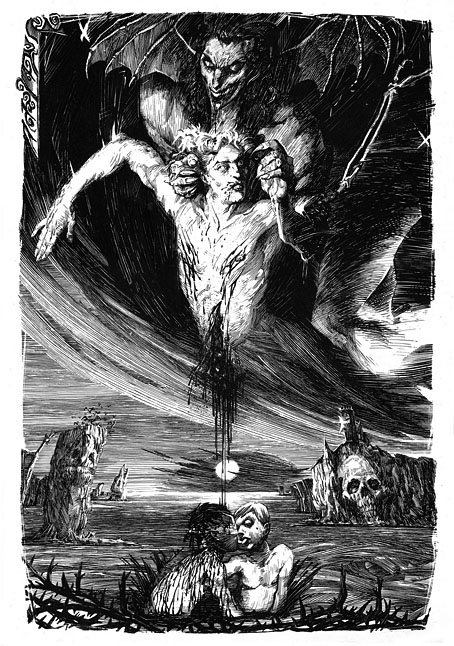

• 2008 is turning out to be a great year for Lovecraft aficionados. As well as the stupendous Lovecraft Retrospective: Artists Inspired by HP Lovecraft, we’re also awaiting Frank Woodford’s feature length documentary, Lovecraft: Fear of the Unknown. I’m lucky to have my work included in Frank’s film which is easily the best documentary to date concerning the life and work of HPL. Among the interviewees are Neil Gaiman, John Carpenter, Guillermo Del Toro, Caitlin R Kiernan, Peter Straub, Ramsey Campbell and Lovecraft scholar ST Joshi. The film will receive its first (?) public screening later this month at the San Diego Comic Con:

Thursday, July 24

8:00–9:45pm

Room 26AB

• Over the weekend Arthur Magazine cleared the $20,000 it needed to keep running before the three-day deadline elapsed. A stunning piece of fund-raising which shows how much people value Jay and company’s efforts.

• The gorgeous cover above is the work of Frank X Leyendecker (1876–1924), brother of the more well-known (and gay) Joseph C Leyendecker. Makes me think I should make a post of Butterfly Women if only as an excuse to track down more pictures of Loie Fuller.

• Last but not least: happy birthday Lorraine!