It’s that man again. Presenting the latest reworked page from the ongoing reconstruction/improvement of my Haunter of the Dark book. The picture will illustrate “Abdul Alhazred”, the final section of Alan Moore’s text for The Great Old Ones in which HP Lovecraft is positioned at Malkuth, the “Kingdom” in Alan’s eldritch Kabbalah. This makes Lovecraft himself the receptive vessel of the energies descending from the spheres above, while paradoxically being the source of those energies. Or some of them at least… The Great Old Ones is a Mythos Kabbalah which features Dagon, Hastur, Tsathoggua and Yig as well as Cthulhu and the rest. Alan doesn’t subscribe to Kenneth Grant’s baseless theory that Lovecraft really was a receptacle for transmissions from interdimensional entities, but the incorporation of the writer into his own pantheon isn’t unprecedented. Abdul Alhazred was a childhood persona of Lovecraft’s before he assigned the name to the author of Al Azif, or the Necronomicon; further personas may be found in Through the Gates of the Silver Key (“Ward Phillips”), Robert Bloch’s The Suicide in the Study (“Luveh-Keraph, priest of Bast”), and other fictions.

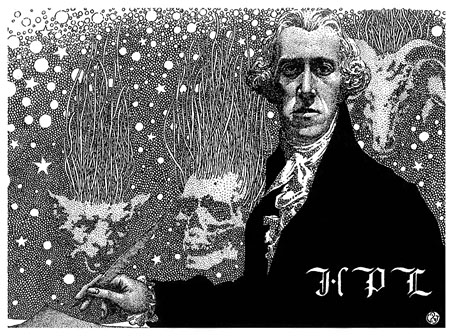

HPL (1937) by Virgil Finlay.

Whether this literary sport warrants the apparently limitless production of Lovecraftian art featuring the man himself, usually sprouting or festooned with tentacles, is a debatable matter. Virgil Finlay began the fantastic portrait trend in 1937 with his memorial depiction of the author writing with a quill pen while dressed in 18th-century garb. The earliest example that I can think of showing Lovecraft paired with the ubiquitous tentacles was the Moebius cover for Lettres d’Arkham in 1975, although there may well be other drawings prior to this. I’ve often wondered what Lovecraft would have made of the deluge of publications and images derived from his work, especially those that place him inside the products of his imagination.

Cover art by Moebius, 1975.

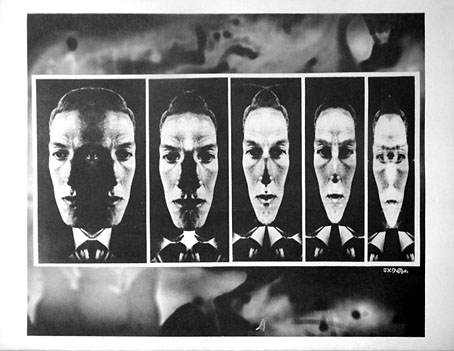

And speaking of which… I was at a loss at first with how to approach a new Lovecraft portrait, all I knew was that one was necessary. The original Malkuth picture from 1999 is another poor Photoshop job which has nevertheless been reused elsewhere on a few occasions, even appearing in 2007 on the cover of an issue of FATE magazine. For the new version I started with the portrait itself, using white lines on black to copy the same portrait photograph that formed the centre of the older picture. This was then duplicated and flipped horizontally to create a kind of Janus head which gives the portrait a suitably weird quality without wreathing it in tentacles. The mirrored head harks back to a sequence of treated photos by JK Potter which I first saw in the Heavy Metal Lovecraft special in 1979. Potter had used the same portrait photo to create effects that were somewhat compromised by poor reproduction, leading me to be believe that I’d created something slightly different to the first panel in his sequence. While researching this post I turned up an earlier version of the artwork which appeared on the back of the first issue of a US fanzine, Fantasy Mongers, also in 1979. The clearer reproduction revealed that the first head in Potter’s sequence is almost identical to my own. Ah well…

Photo art by JK Potter from the back cover of Fantasy Mongers #1, 1979.

The rest of the picture was improvised around this central image. Having drawn the portrait in white-on-black I decided to use a similar technique for the other elements. The Cthulhoid pillars are based on those in my Red-Night Rites painting from 1997, one of which appeared in the 1999 picture. The smaller figure on the right is from one of the photos that Wilfred Talman took while wandering the streets of New York with Lovecraft and Frank Belknap Long. This also appeared in the 1999 picture but for the new version I’ve emphasised what appears to be a book that Lovecraft is carrying in his right hand. Searching around for a complementary figure that might represent Abdul Alhazred turned up a 19th-century photo of a character who not only looked the part but is also standing in a manner similar to the Talman Lovecraft. If you look closely he’s also carrying a book, an addition of my own which turns him into the author of Al Azif. The polyhedra supporting the pair aren’t as arbitrary as they may seem. The spheres serve a dual purpose, preventing the figures from floating in space (or standing in water) while also relating to the Sephiroth of Malkuth which is identified with the Earth in the Kabbalistic scheme of planetary associations.

The next reworked picture will be Tsathoggua which is being polished rather than completely overhauled. I’m hoping I might have this done by the end of the month but I’m still chipping away at The Dunwich Horror while doing all this, as well as working on things which pay the bills. (I’ve just finished designing and illustrating another book.) Further progress will be announced in due course.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Lovecraft archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Return of the Crawling Chaos

• Lettering Lovecraft

• Weird ekphrasis and the Dunwich Horrors

• Kadath and Yog-Sothoth

• Another view over Yuggoth