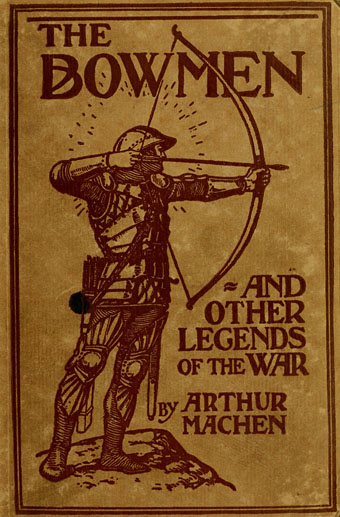

The Bowmen was a short piece of fiction by Arthur Machen published in a London newspaper, The Evening News, on the 29th September, 1914. By Machen’s standards it’s not one of his best pieces, written at a time when he was working at the paper as a journalist. The First World War was in its early days, and the story was conceived as a Kipling-like morale-boost following the retreat of British forces at Mons a few weeks before. The stories for which Machen is remembered today had never provided the success he hoped for so it must have been a surprise when his invention of angelic bowmen appearing during the battle gained him national attention:

On the last Sunday in August, 1914, Machen read in his morning paper of the retreat from Mons.

“I no longer recollect the details, but I have not forgotten the impression that was then made on my mind. I seemed to see a furnace of torment and death and agony and terror seven times heated, and in the midst of the burning was the British army: in the midst of the flame, consumed by it, scattered like ashes and yet triumphant, martyred and for ever glorious.”

That was the way, indeed, in which the English thought about the army at the beginning of the Great War; since then we have come to take a less romantic view of warfare. With this picture in his mind, Machen conceived and wrote a story called The Bowmen, told, as most stories are, as if it were true—that is, he did not begin by saying: “what you are about to read is all my own invention”—in which St. George with an army of English mediaeval bowmen appeared at the critical moment to cover the British retreat. Not, to be sure, a very probable story nor, as Oswald Barron pointed out, was it likely that the Agincourt bowmen, most of whom came from Wales, would use the French expressions Machen evokes from them: and Machen himself felt he had not done justice to his original conception.

“But if I had failed in the art of letters, I had succeeded, unwittingly, in the art of deceit.”

The Bowmen appeared in The Evening News on September 29th, 1914, at a moment when people were looking for a miracle, and many promptly embraced it as an account of one. That such journals as The Occult Review and Light should fasten on it, might have been anticipated; but it was taken up by parish magazines all over the country, and people came forward on every side to say that they had friends and relatives who had seen the “Angels of Mons” with their own eyes. As a result, Machen became, for the first time in his life, a man of nation-wide fame. To thousands of people, the idea, whether true or false, gave consolation or hope, but when Machen protested that his story was entirely the child of his own imagination, the fame threatened to turn to notoriety; he was rebuked for his impudence at claiming originality for the tale. Nevertheless a legend had been born and a shoal of publications appeared to satisfy public demand—On the Side of the Angels (Harold Begbie), Guardian Angels (GP Kerry—a sermon reprinted), Angels, Saints and Bowmen of Mons (IE Taylor, Theosophical Publishing Society).

Aidan Reynolds & William Charlton in Arthur Machen: A Short Account of His Life and Work (John Baker, 1963)