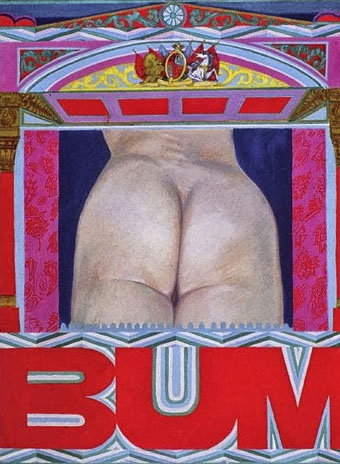

Bum (1966) by Pauline Boty.

• Eleanor Birne on Pauline Boty, “the only prominent female Pop artist among a generation of famous men”. Ken Russell’s Pop Art documentary, Pop Goes the Easel (1962), which features Boty, may be seen here. Two years later Boty was back with Ken Russell playing the part of the prostitute from The Miraculous Mandarin in a film about Béla Bartók. That’s something I’d love to see. There’s more about her painting, and the work of other female Pop artists, here.

• Why Are We Sleeping? Mark Pilkington on the music world’s recurrent interest in the philosophy of GI Gurdjieff. Pilkington’s most recent Raagnagrok release with Zali Krishna, Man Woman Birth Death Infinity, was reviewed by Peter Bebergal.

• Cinematic details: Frames-within-frames in The Ipcress File (1966), and the typography of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

A Jay Shaw poster for Ben Wheatley’s forthcoming film of High-Rise.

• “…a large cavity must be dug in the bird’s shoulder and filled with ball bearings.” Christine Baumgarthuber on the dubious delights of The Futurist Cookbook.

• Why Tatlin Can Never Go Home Again: Rick Poynor on the difficulties of finding a definitive representation of an artwork online.

• Jay Parini reviews Inside a Pearl: My Years in Paris by Edmund White. At AnOther Donatien Grau talks to White about fashion.

• At Bajo el Signo de Libra (in Spanish): the homoerotic and occasionally Surrealist art of Pavel Tchelitchew.

• At 50 Watts: Kling Klang Gloria: Vintage Children’s Books from Austria.

• The motorbike girl gangs of Morocco photographed by Hassan Hajjaj.

• Geoff Manaugh on how LED streetlights will change cinema.

• Stylus “is an experiment in sound, music and listening”.

• Mix of the week: Secret Thirteen mix 106 by Senking.

• At Pinterest: JG Ballard

• This Is Pop? (1978) by XTC | Pop Muzik (1979) by M | Pop Quiz (1995) by Stereolab