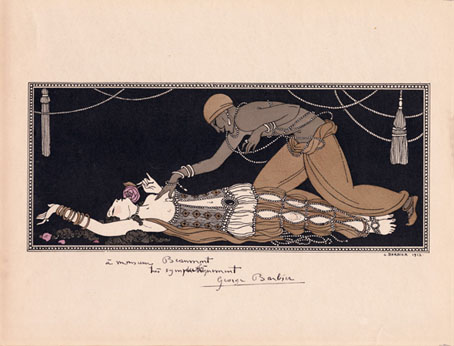

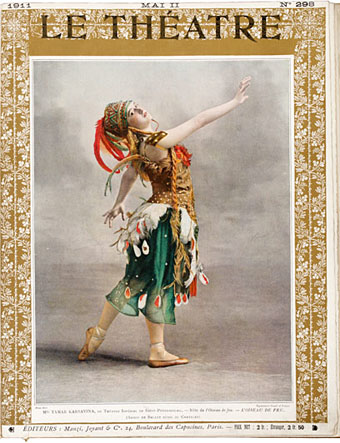

This week sees the centenary of the first performance by Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes of The Rite of Spring at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris. Everyone is familiar with the details of that momentous occasion, and Stravinsky’s score is probably performed more frequently today than any of his other works. Less familiar is the nature of the ballet which caused so much outrage. A combination of the hectic schedule of the Ballets Russes and the loss of choreographer Nijinsky a few months later meant that the choreography was never properly transcribed. This caused problems for subsequent revivals, and the only reason we have an idea of the radical nature of the ballet is thanks to a decade of research by Millicent Hodson and Kenneth Archer, a pair of cultural archaeologists who’ve specialised in reviving ballets. Hodson and Archer scoured archives looking for details of Nicholas Roerich’s costumes, and also traced surviving members of the 1913 company in order to verify their choreographic researches.

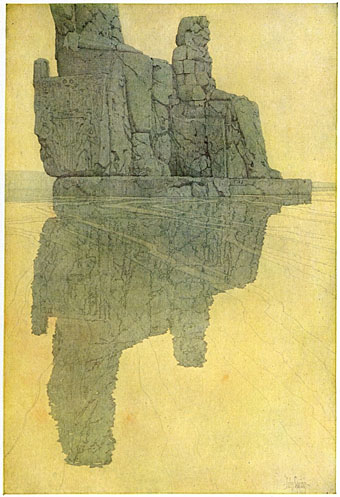

The performance here is a recording of the Joffrey Ballet’s staging of Hodson and Archer’s reconstruction from the late 1980s. I first saw this in 1989 and was aghast at how strange and savage the dancing is compared to classical ballet. Hodson and Archer have since amended some of the performance details but there’s more than enough in this staging to convey why the ballet was so threatening and disturbing to the audience in 1913. Even today, after decades of modern dance it looks surprisingly crude with its dancers stamping their way across the stage. I was also thrilled to see the restoration of Nicholas Roerich’s costumes and decor. In addition to giving the ballet its distinctive look, Roerich contributed the pagan dramaturgy, something that tends to be overlooked when so many big names are competing for attention. (There’s more about Roerich and his involvement with the Rite here.) I always enjoy the way Roerich provides a link between this favourite ballet and the writings of HP Lovecraft. I’ve no idea what Lovecraft would have made of The Rite of Spring but he had a lot of time for Roerich’s paintings, and refers to them in At the Mountains of Madness.

The recording linked here is annoyingly split into three parts (and the soundtrack is hissy mono) but if you’ve any interest in the original ballet it really needs to be seen.

• The Rite of Spring: part one | part two | part three

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Vaslav Nijinsky by Paul Iribe

• Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes

• Pamela Colman Smith’s Russian Ballet

• Le Sacre du Printemps

• Images of Nijinsky