Cadeau Audace by Man Ray (1921).

L’amour fou by Robert Hughes

Fur teacups, wheelbarrow chairs, lip-shaped sofas … the fashion, furniture and jewellery created by the Surrealists were useless, unique, decadent and, above all, very sexy.

The Guardian, Saturday March 24th, 2007

THE VICTORIA AND Albert’s big show for this year, Surreal Things: Surrealism and Design, is—well, maybe we don’t much like the word “definitive”. But it’s certainly the first of its kind.

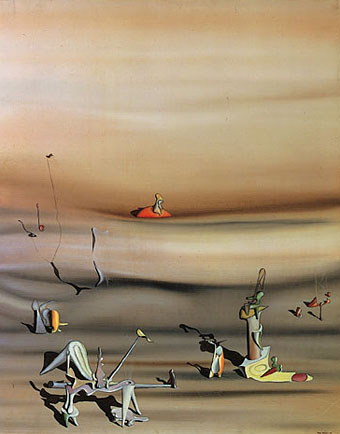

Everyone knows something about surrealism, the most popular art movement of the 20th century. The word has spread so far that people now say “surreal” when all they mean is “odd”, “totally weird” or “unexpected”. No doubt this would give heartburn to André Breton, the pope of the movement nearly a century ago, who took the title from his friend, the poet Guillaume Apollinaire, who had called his play The Breasts of Tiresias, “a surrealist drama”. But too late now. The term is many years out of its box and, through imprecision, has achieved something akin to eternal life. Surrealist painting and film, that is. In fact, some surrealist images have imprinted themselves so deeply and brightly on our ideas of visual imagery that we can’t imagine modern art (or, in fact, the idea of modernity itself) without them.

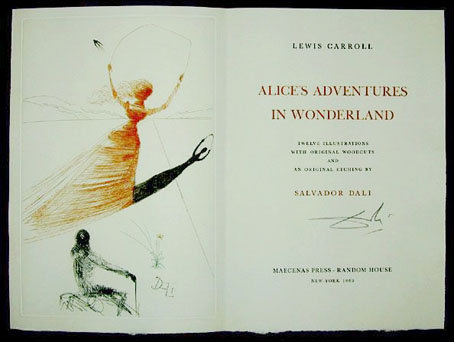

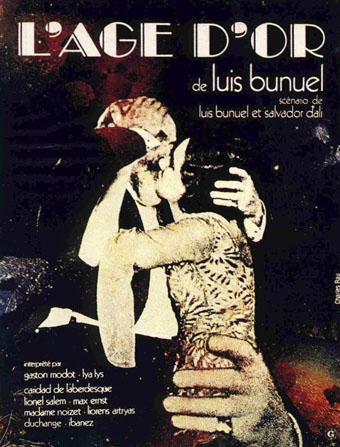

Think Salvador Dalí and his soft watches in The Persistence of Memory. Think Dalí again, in cahoots with Luis Buñuel, and the cut-throat razor slicing through the girl’s eye, as a sliver of cloud crosses the moon (actually, the eye belongs to a dead cow, but you never think this when you see their now venerable but forever fresh movie An Andalusian Dog, 1929). Think of photographer Man Ray’s fabulous Cadeau Audace (‘Risky Present’, 1921), the flatiron to whose sole a row of tacks was soldered, guaranteeing the destruction of any dress it would be used on. Think of Rene Magritte’s The Rape, that hauntingly concise pubic face, with nipples for eyes and the hairy triangle where the mouth should be. Think of the shock, the horniness, the rebellion, the unwavering focus on creative freedom, the obsessive efforts to discover the new in the old by disclosure of the hidden…

Continues here

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Surrealist Revolution

• Surrealist Women

• Las Pozas and Edward James

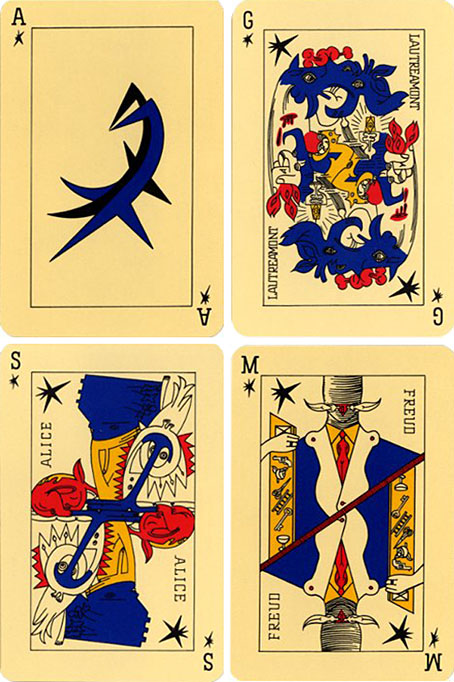

• Surrealist cartomancy