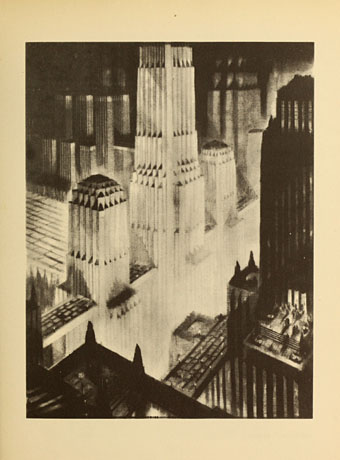

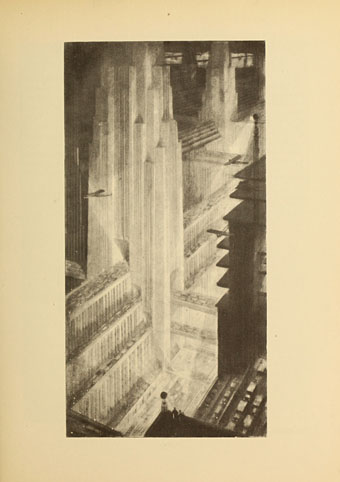

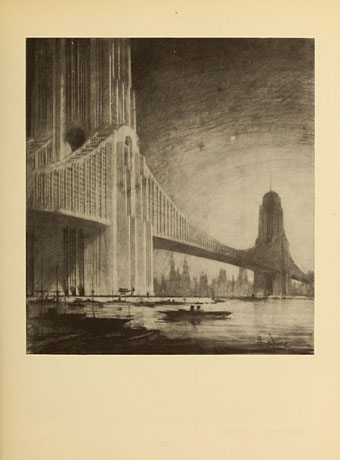

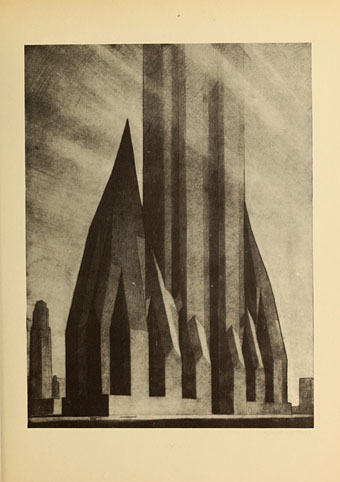

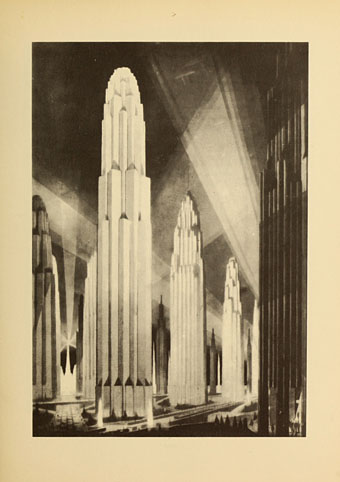

Crowding Towers.

The work of architectural renderer Hugh Ferriss (1889–1962) has appeared here before. The Metropolis of Tomorrow (1929) was a major influence on the architectural style I deployed in the Reverbstorm series, together with Berenice Abbott’s photographs of New York City in the 1930s. Ferriss’s hazy proposals for cities of the future are more visible today than they used to be thanks to the popularity of those sites that enjoy outmoded visions of the future.

Flickr has been a good source of Ferriss’s drawings in the past but the Internet Archive recently posted the entirety of The Metropolis of Tomorrow, pages as well as pictures. The book appeared a couple of years after Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, and shares that film’s idea of the future city as a kind of superannuated New York. Skyscrapers were still a relatively new idea so this seemed a natural development at the time, as did the concept of super-highways and rooftop aerodromes. Human beings in Ferriss’s future are either ant-like specks or they’ve vanished altogether among the massed ranks of towers which often look more like less like buildings and more like Art Deco spacecraft. Lang’s vision was dystopian only in the way it relegated its workers to the underworld, while Ferriss’s proposals were wholly optimistic. Looking back we’re more aware of the shortcomings of such ideas, and from my perspective it wasn’t so difficult to bring out the latent menace inherent in these megastructures. Ferriss’s metropolis, like that of Fritz Lang, is a fun place to visit but you wouldn’t necessarily want to live there.

Browse the rest of the book here or download it here.

Overhead traffic-ways.

Apartments on bridges.

Evolution of the set-back building: second stage.

Verticals on wide avenues.

Continue reading “The Metropolis of Tomorrow by Hugh Ferriss”