Cover art by Leo Morey.

To HP Lovecraft, Pluto was the planet Yuggoth, home to the fungoid, brain-harvesting Mi-go whose exploits are detailed in The Whisperer in Darkness (1931). Clark Ashton Smith wasn’t averse to imagining the planets of the Solar System as exotic worlds, but in The Plutonian Drug, a short story published in Amazing Stories for September 1934, he stayed closer to what was known of Pluto at the time, albeit with an exception or two:

“There are some other drugs, comparatively little known, whose effects, if possible, are even more curious than those of mnophka. I don’t suppose you have ever heard of plutonium?”

“No, I haven’t,” admitted Balcoth. “Tell me about it.”

“I can do even better than that — I can show you some of the stuff, though it isn’t much to look at — merely a fine white powder.”

Dr. Manners rose from the pneumatic-cushioned chair in which he sat facing his guest, and went to a large cabinet of synthetic ebony, whose shelves were crowded with flasks, bottles, tubes, and cartons of various sizes and forms. Returning, he handed to Balcoth a squat and tiny vial, two-thirds filled with a starchy substance.

“Plutonium,” explained Manners, “as its name would indicate, comes from forlorn, frozen Pluto, which only one terrestrial expedition has so far visited — the expedition led by the Cornell brothers, John and Augustine, which started in 1990 and did not return to earth till 1996, when nearly everyone had given it up as lost. John, as you may have heard, died during the returning voyage, together with half the personnel of the expedition: and the others reached earth with only one reserve oxygen-tank remaining.

This vial contains about a tenth of the existing supply of plutonium. Augustine Cornell, who is an old school friend of mine gave it to me three years ago, just before he embarked with the Allan Farquar crowd. I count myself pretty lucky to own anything so rare.

“The geologists of the party found the stuff when they began prying beneath the solidified gases that cover the surface of that dim, starlit planet, in an effort to learn a little about its composition and history. They couldn’t do much under the circumstances, with limited time and equipment; but they made some curious discoveries — of which plutonium was far from being the least.

“Like selenine, the stuff is a bi-product of vegetable fossilization. Doubtless it is many billion years old, and dates back to the time when Pluto possessed enough internal heat to make possible the development of certain rudimentary plant-forms on its blind surface. It must have had an atmosphere then; though no evidence of former animal-life was found by the Cornells.

“Plutonium, in addition to carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and oxygen, contains minute quantities of several unclassified elements. It was discovered in a crystalloid condition, but turned immediately to the fine powder that you see, as soon as it was exposed to air in the rocketship. It is readily soluble in water, forming a permanent colloid, without the least sign of deposit, no matter how long it remains in suspension.”

“You say it is a drug?” queried Balcoth. “What does it do to you?”

“I”ll come to that in a minute — though the effect is pretty hard to describe. The properties of the stuff were discovered by chance: on the return journey from Pluto, a member of the expedition, half delirious with space-fever, got hold of the unmarked jar containing it and took a small dose, imagining that it was bromide of potassium. It served to complicate his delirium for a while — since it gave him some brand-new ideas about space and time.

“Other people have experimented with it since then. The effects are quite brief (the influence never lasts more than half an hour) and they vary considerably with the individual. There is no bad aftermath, either neural, mental, or physical, as far as anyone has been able to determine. I”ve taken it myself, once or twice, and can testify to that.

“Just what it does to one, I am not sure. Perhaps it merely produces a derangement or metamorphosis of sensations, like hashish; or perhaps it serves to stimulate some rudimentary organ, some dormant sense of the human brain. At any rate there is, as clearly as I can put it, an altering of the perception of time — of actual duration — into a sort of space-perception. One sees the past, and also the future, in relation to one’s own physical self, like a landscape stretching away on either hand. You don’t see very far, it is true — merely the events of a few hours in each direction; but it’s a very curious experience; and it helps to give you a new slant on the mystery of time and space. It is altogether different from the delusions of mnophka.”

The most immediately notable detail here is the word “plutonium” which Smith was using as his own six years before the radioactive element was officially named. (By coincidence, transuranic plutonium was discovered the year Smith’s story was published.) Also of note is yet more discussion in a Smith story of real drugs such as opium and hashish. I’ve never seen any evidence that Smith was a drug user but he was happy to exploit the visionary potential of these substances. The time-viewing effects of Smith’s plutonium might have made for an effective weird tale but the piece runs out of steam fairly quickly; this is one of those stories with a promising idea that needs someone like HG Wells to do it justice. Many of Smith’s stories were written in haste so this isn’t too surprising but The Plutonian Drug lacks the imaginative scope of a piece of psychedelic science fiction like The City of the Singing Flame. Nevertheless, it was druggy enough to open Michel Parry’s Strange Ecstasies which is how I came to revisit it recently.

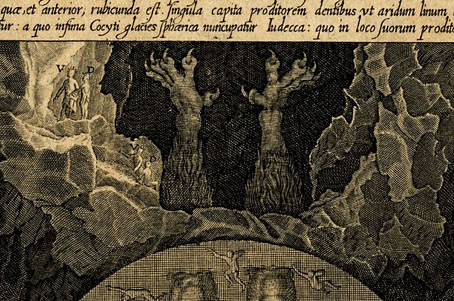

I was hoping the story might have been illustrated for its early printings but it seems not. The best I can find is this card design; there’s also a metal song by a band named Innsmouth that was released as a double-bill single in 2012. Smith’s story may be read in full at Eldritch Dark.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• More trip texts

• Yuggoth details

• The Garden of Adompha

• The City of the Singing Flame

• Haschisch Hallucinations by HE Gowers

• Odes and Sonnets by Clark Ashton Smith

• Clark Ashton Smith book covers