Writing about the late Lynn Redgrave last year I picked out this film as a career highlight despite not having seen it for a very long time. Watching it again recently was an interesting experience, not least for the way it connects to more recent points of obsession, none of them evident the first time round.

Carnaby Street antics.

Smashing Time was directed by Desmond Davies in 1967, and the direction is as perfunctory as you’d expect from someone whose career before and after was mostly for television. Of more interest is the script by George Melly, a bisexual jazz singer, writer, and lifelong evangelist for Surrealist art. This was Melly’s first job as a screenwriter and he seems an odd choice. He was 41 at the time, and his portrayal of Swinging London and its denizens is often typical of the acerbic older generation’s view of the younger groovers. It’s never as cynical as the Private Eye crowd but without Melly’s humour the tone might seem patronising. That said, it was the satire magazine that originated the names of the two lead characters, Brenda (Rita Tushingham) and Yvonne (Lynn Redgrave) being Private Eye‘s names for Queen Elizabeth and Princess Margaret respectively. The story is a simple one of the pair coming to London from the north of England in search of “a smashing time”, and, in Yvonne’s case, an attempt to make it big somehow. Misadventures ensue.

Brenda in the Too Much boutique.

Along the way there are digs at avant-garde artists, lecherous men, greedy pop promoters and wealthy boutique owners. Melly leavens his barbs with yet another example of the Lewis Carroll influence on late-60s culture. One of the scenes takes place in the Jabberwock Gallery, while Jabberwocky-derived character names appear throughout: Tom Wabe (Michael York), Charlotte Brillig, Mrs Gimble (the always wonderful Irene Handl), Bobby Mome-Rath (Ian Carmichael), Jeremy Tove. There’s also an Alice Boojum, and a band named The Snarks (real-life psych band Tomorrow) who don’t get to play, unfortunately. Tomorrow, who appear in the final party scene, are the sole connection with the genuinely hip London of 1967. Everything else we see is the Sunday supplement view of the city with Carnaby Street, shots of Chelsea and a dishevelled Camden. The raucous finale is staged at the top of that bright new landmark of 1960s London, the Post Office Tower.

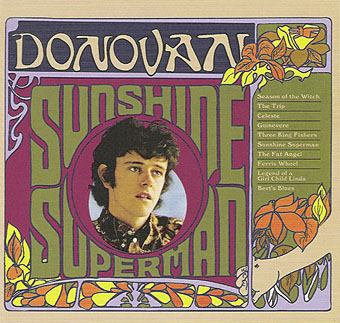

Yvonne begins her pop career.

My childhood enthusiasm was obviously taken with the film’s superficial qualities—there are so many songs it’s almost a musical—whereas now I’m impatient with the laboured slapstick but enjoy all the peripheral stuff. Many of the documentary shots of streets away from the centre are a reminder of how shabby and grimy the capital really was at that time, as was the rest of Britain when there was still a century of industrial soot on the walls. I also realise I’d missed the double-meaning of the title: “smashing time” isn’t only a modish phrase for an enjoyable experience but a nod to the way Brenda and Yvonne cause havoc wherever they go. The jabs from an older musician at brainless pop culture would have annoyed some but Yvonne’s hit song, I’m So Young (which is actually very good), has lyrics which resonate today:

I can’t sing but I’m young

I can’t do a thing but I’m young

I’m a fool

But I’m cool

Don’t put me down

Lynne Redgrave is fantastic as Yvonne, completely convincing in a part that requires her to be loud, selfish and petulant without ever being too obnoxious. She also wears a different wig in nearly every scene. Among other moments of note there’s some fleeting gay humour with a pair of waiters camping it up in the Sweeney Todd pie shop (as does Murray Melvin in another scene). And there’s also an incident which, being an Aubrey Beardsley obsessive, I have to draw attention to:

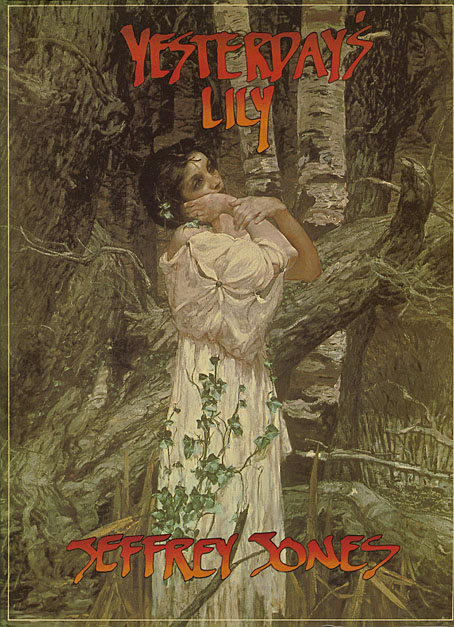

Was this the first appearance of Beardsley’s work in cinema? The V&A exhibition which began the Beardsley revival had taken place only a year before, and I can’t think of any examples earlier than this. The William Morris wallpaper is a fitting touch as well.

Reservations aside, this is a film I could watch more often than “properly” psychedelic fare like Wonderwall. For a snapshot of the period, it’s still a smash, baby.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Lynn Redgrave, 1943–2010

• Through the Wonderwall