The Artists’ Studio (1906).

This week’s post is another by Sander Bink about a neglected artist of the Dutch fin de siècle. There’s no need for me to add a great deal to Sander’s appraisal below other than to point out the evident debt that Antoon Van Welie seems to owe to the Pre-Raphaelites for whom Ophelia was a popular subject. British artists of the 19th century have often been criticised for adding little to the evolution of Continental art but the influence of the Pre-Raphaelites and the Arts and Crafts movement pervades European Symbolism. My thanks again to Sander for the post.

* * *

Antoon van Welie (Dutch Wikipedia only) was a Dutch painter known mainly for his portraits of the rich and famous. Around 1900 his work was praised by writers and critics such as Camille Mauclair, Jean Lorrain and Anatole France. He had studios in The Hague, London, Paris and The Vatican. There’s not much information about him in English, and for a long time there wasn’t a great deal in Dutch either, since during his lifetime he was already more or less forgotten. His being openly gay could have been one of the reasons. Male beauty is one of his subjects, as illustrated by The Artists’ Studio. His preference for depicting Catholic priests and flamboyant society ladies might also have been a little too extravagant for Dutch artistic standards of the period. The influence of Symbolism and mysticism on his work sets him a little apart from the crowd as well. All this does make him somewhat of a “decadent” or fin de siècle artist. What surely did not help his posthumous fame was a portrait of Mussolini he painted in 1921, and apparently he later also made one of Hitler. But in 2003 he was rescued from art-historical oblivion by the good people of the Louis Couperus Museum in The Hague. An exhibition there was followed in 2007 by a larger one at Museum Het Valkhoff in Nijmegen: The Last Decadent Painter. The book published for the occasion gives an extensive overview of Van Welie’s life and oeuvre but is unfortunately only available in Dutch.

The portraits which made him famous in his day are, in my opinion, technically not that great and sometimes tend toward kitsch. More subtle and beautiful are his early Symbolist works which, like those by Simon Moulijn, are strongly influenced by Maeterlinck’s neo-mystical writings.

Aglavaine en Sélysette (1899).

Some quite refined examples are the lithograph Aglavaine en Sélysette and the pastel Les Princesses de Légende, both directly inspired by Maeterlinck’s plays.

Les Princesses de Légende (1899).

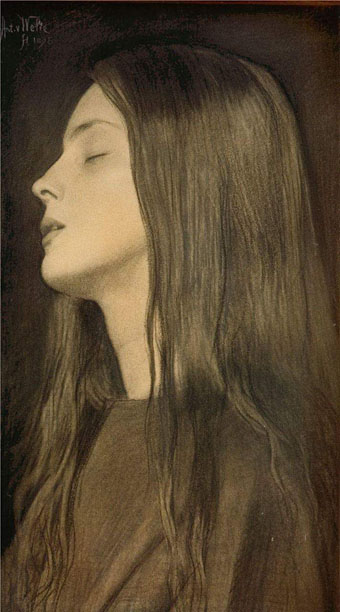

Ophelia.

Literature was an important influence, as it was for many other Symbolist painters, and Van Welie duly produced the pastel Ophelia in 1898–’99. The same goes for musical themes, an example of which is the serene pastel Holy Cecilia with Lyre.

Holy Cecilia with Lyre (1899).

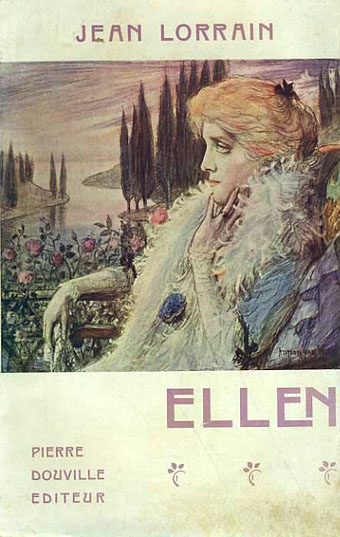

He also designed book covers like the one for Jean Lorrain’s novel Ellen from 1906.

La Douleur (1895).

But his most attractive work and as far as I am concerned one of the finest works of 1890s Dutch art is the chalk drawing La Douleur. Although the title emphasizes the young lady’s suffering, she also seems to be in a (sexual) ecstasy. A paradoxical beauty like Baudelaire’s femmes damnées: “de terribles plaisirs et d’affreuses douceurs”.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The gay artists archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The art of Simon Moulijn, 1866–1948

• René Gockinga revisited

• Gockinga’s Bacchanal and an unknown portrait of Fritz Klein

• More from the Decadent Dutch