I thought about calling this one A Young Person’s Guide to Echo Guitar but that would only end up attracting people expecting a tutorial of some kind. It’s not really a guide either, more an overview of a musical idiom whose predominant feature is guitar played through analogue or digital echo machines, often without additional instrumentation. I have a predilection for this kind of thing, something I was thinking about recently when listening to Michael Brook’s Cobalt Blue album.

A Watkins Copicat as seen (and used) in Berberian Sound Studio.

This is also another example of technology inspiring the development of new forms of music. Echoed guitar dates back to the early days of rock’n’roll but it was the advent of echo machines like the Watkins Copicat that made it possible for guitarists to produce rich clusters of sound without any other instrumentation. The Copicat was portable and could be activated with a foot pedal, making it perfect for guitar players. These machines aren’t always credited in album notes but I’d guess that one or two of the earlier recordings on this list have been made using Copicats. (John Martyn, however, preferred an Echoplex.) As for the more recent examples, one reason to write this piece is to fish for suggestions of things I may have missed. I’m sure I put a Bandcamp discovery in one of the weekend lists that involved quantities of echo guitar but I’m going to have to trawl back through old posts to find it.

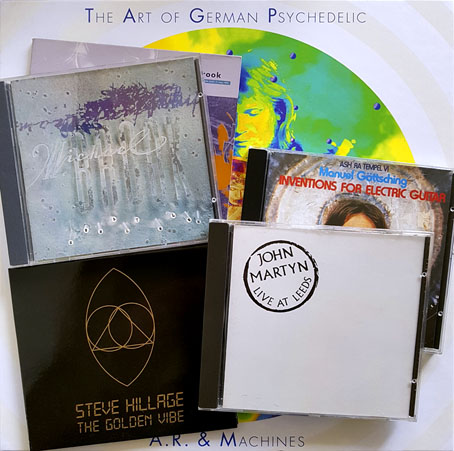

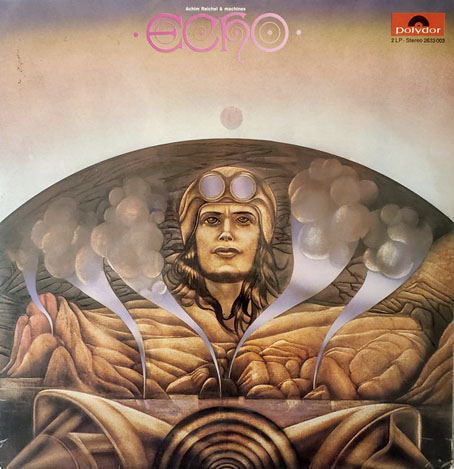

Echo (1972) by Achim Reichel and Machines

Achim Reichel is an odd character in German music. In the 1960s he was a singer and guitarist in a popular Beatles-like band, The Rattles, followed by a stint with a short-lived psychedelic outfit, Wonderland; by the 1980s he was a very successful German pop artist. For a few years in the 1970s, however, he recorded a handful of albums which in later years he seems to have found embarrassing despite their being regarded now as highlights of the so-called Krautrock era. Echo is the most adventurous of these, a double album which used to be a frustrating item, being praised by those who heard it while also being very difficult to find. The two discs contain four suites that fill each side, the first one opening with long stretches of echo-guitar which soon establish the mood of the album with their unpredictable evolution. Echo as a whole is a succession of unexpected swerves and musical detours, taking in orchestral arrangements, field recordings, snatches of song, heavy rock, and (regrettably) a long stretch of glossolalic jabbering that tests the listener’s patience. I forgive the latter when the rest of the album is so good. The guitar sound that Reichel developed here became a recurrent feature of his music for the next two years, especially in live performances.

Reichel’s popularity has overshadowed his earlier recordings to an extent that Echo wasn’t given an official reissue until 2017 when he relented to persistent requests and put together a 10-disc CD set, The Art Of German Psychedelic 1970–74. This is too much Reichel for the casual listener but if you can bear his occasional lurches into Steppenwolf-style psych-rock there’s a great deal of excellent music in the collection. Among the exclusive offerings is a superb live performance of kosmische improvisation from 1973, also an entire disc of unaccompanied echo-guitar recordings.

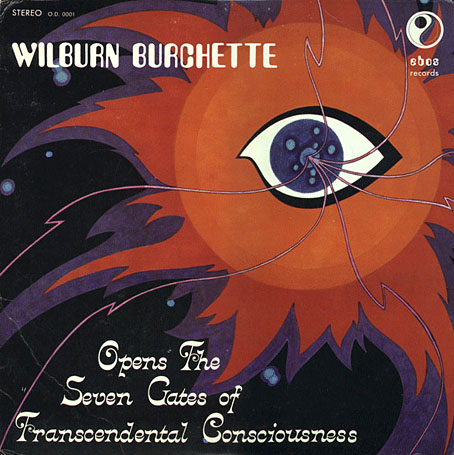

Wilburn Burchette Opens The Seven Gates Of Transcendental Consciousness (1972)

Many of Wilburn Burchette’s albums would be suitable here but I chose this one because I like the title and it has the grooviest cover. Burchette’s subtitle—“A Transcendental Ballet For The Mind Of God”—suggests something more overtly cosmic than the music itself which is less freeform than Achim Reichel. This is also the first self-released album in a list which coincidentally contains several such releases.

• Opens the Seven Gates of Transcendental Consciousness

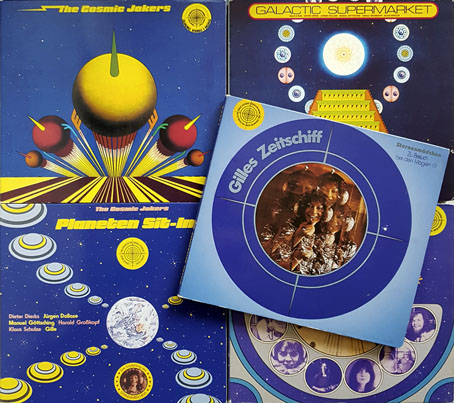

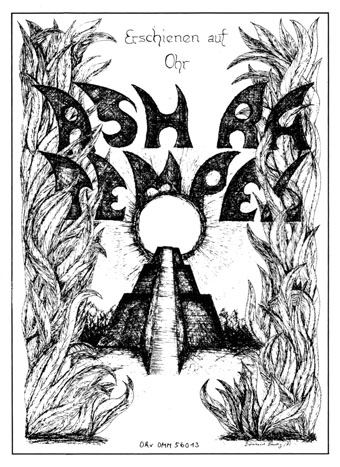

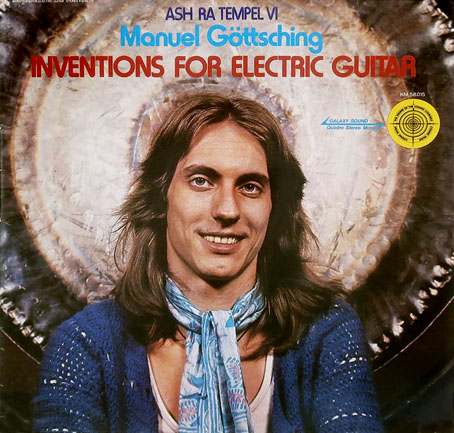

Inventions For Electric Guitar (1974) by Ash Ra Tempel/Manuel Göttsching

Cult album time. This one was labeled as the sixth release by Ash Ra Tempel but it’s really the first solo album by Manuel Göttsching, in which he used multi-track recording together with copious echo and other effects to create something that sounds more like the synthesizer music of 1974 than anything made with guitars. The cover art fixes the album in a specific time but the music itself is timeless. In 2010 he performed the album in its entirety at a Japanese music festival, assisted by three other guitarists: Steve Hillage, Elliott Sharp and Zhang Shouwang. If there’s a complete video of this concert I’ve yet to see it but there is this extract showing the musicians playing Pluralis.