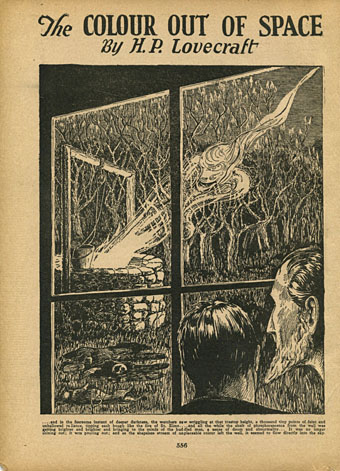

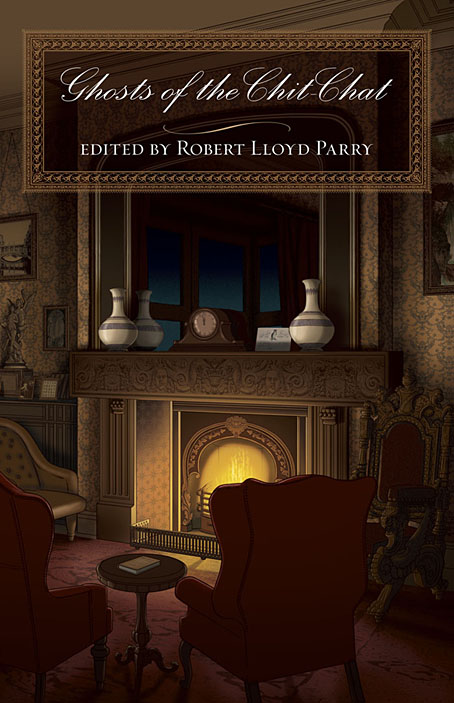

My latest cover for Swan River Press is very suitable for the season, It’s also a good example of the “window” type of cover design, where you show a view into a scene rather than a flat design. Window covers are common in fantasy and science fiction, less so in the horror genre where you often want to avoid giving too much away. The “Chit-Chat” of the title was The Chit-Chat Club, a group of students and tutors at King’s College, Cambridge:

On the evening of Saturday, 28 October 1893, Cambridge University’s Chit-Chat Club convened its 601st meeting. Ten members and one guest gathered in the rooms of Montague Rhodes James, the Junior Dean of King’s College, and listened — with increasing absorption one suspects — as their host read “Two Ghost Stories”.

Ghosts of the Chit-Chat celebrates this momentous event in the history of supernatural literature, the earliest dated record we have of M. R. James reading his ghost stories out loud. And it revives the contributions that other members made to the genre; men of imagination who invoked the ghostly in their work, and who are now themselves shades. In a series of essays, stories, and poems Robert Lloyd Parry looks at the history and culture of the Club.

In addition to tales and poems never before reprinted, Ghosts of the Chit-Chat features earlier, slightly different versions of two of M. R. James’s best-known ghost stories; Robert Lloyd Parry’s profiles and commentaries on each featured Chit-Chat member sheds new light on this supernatural tradition, making Ghosts of the Chit-Chat a valuable resource for casual readers and long-time Jamesians alike. (more)

The full picture which will be a little cropped on the print version. Here you get to see more aspidistra.

The brief for the cover was to show a view of an empty room in a manner similar to the covers drawn by “Ionicus” (Joshua Charles Armitage) in the 1970s and 80s for a series of supernatural story collections. After looking at a number of these covers I took Tune in for Fear as a template; I liked the angle of the picture which offered a view of a welcoming fireplace to contrast with the night sky seen on the back of the book, and the two-point perspective makes a change from my tendency to create symmetrical pictures. The inhabitants of the Ionicus room seem to have either fled or been abducted whereas mine have either just left or are soon to arrive. The clock on the mantelpiece is almost at midnight, and there’s a Chit-Chat invitation next to it so I’d suggest the latter. The picture contains a number of references to the stories and poems in the book, although not as many as I’d originally intended when several of the pieces proved resistant to having their contents reduced to a single detail. I won’t list everything here since I’d prefer readers to try and match the details themselves.

Ghosts of the Chit-Chat will be published in December, and is available for pre-order here.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Far Tower: Stories for WB Yeats

• The Scarlet Soul: Stories for Dorian Gray