TV producer & film director Leslie Megahey died at the end of August but the news has taken a while to filter through to these pages where his BBC TV productions have been the subject of several posts. My recurrent comments about his work were effusive enough for him to send me a handwritten note of thanks a few years ago, plus a promotional card for one of the films in the Artists and Models series. If more of his productions had been available online or on disc I would have written something about them as well, but old television, especially the documentary variety, remains persistently inaccessible to future audiences.

There are biographical details in the link above so what follows is a list of the Megahey productions that, for this viewer at least, made his name one to look out for in the TV listings. Some of these are on YouTube, a couple are available on disc, while the rest have yet to resurface anywhere. Everything here is highly recommended…if you can find it.

• Omnibus: All Clouds are Clocks (1976/1991): An hour-long interview with composer György Ligeti. I caught this one on its updated rebroadcast in 1991 when Megahey revisited Ligeti to see what directions his career had taken over the past 15 years. Currently unavailable.

• Schalcken the Painter (1979): Another Omnibus film, and a ghost story (after Sheridan Le Fanu) that’s as good as any of the BBC’s MR James adaptations. Released on (Region B) blu-ray & (Region 2) DVD by the BFI.

• Arena: The Orson Welles Story (1982): A two-part interview (165 minutes in total) which caught Welles in a rare mood when he was happy to talk at length about his career. The TV equivalent of the huge book of Peter Bogdanovich conversations. Part One | Part Two

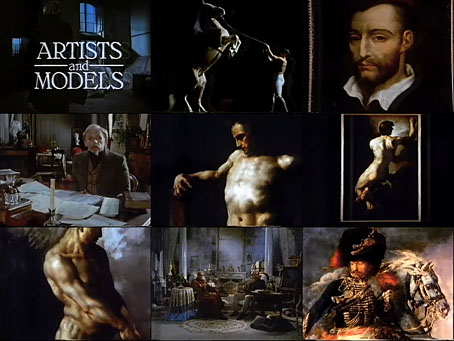

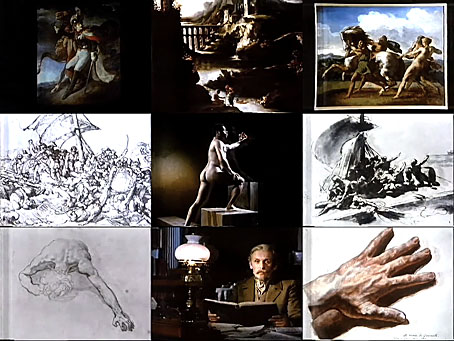

• Artists and Models (1986): Three drama/documentaries about French painters: David, Ingres and Géricault.

• Cariani and the Courtesans (1987): Another historical drama about an artist, Giovanni Cariani (c. 1490–1547). Very much in the mould of Schalcken the Painter but without the supernatural element. Currently unavailable.

• Duke Bluebeard’s Castle (1988): The best film version of Bartók’s opera. The Region 1 DVD by Kultur seems to be deleted but is worth seeking out for having removable subtitles. There’s a copy at YouTube.

• The Complete Citizen Kane (1991): A 90-minute documentary about Welles’ film using extracts from the Arena interviews and the Megahey produced TV series The RKO Story, plus new material. No longer on YouTube (or anywhere else) due to a copyright complaint. This is why I’m always saying you should download these things as soon as you find them.

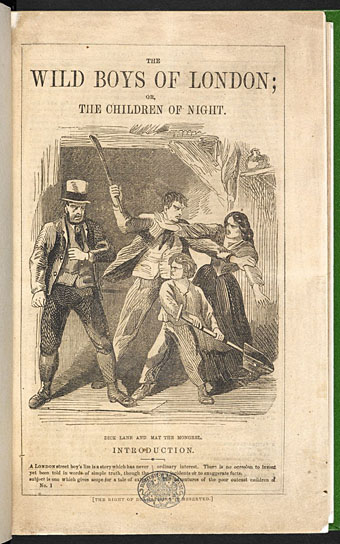

• The Hour of the Pig (1993): A feature film about a medieval animal trial, this one was hacked around by Miramax then released in the US as The Advocate where it flopped. The hard-to-find UK version turned up on YouTube a few days ago.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Men and Wild Horses: Théodore Géricault

• The Complete Citizen Kane

• Schalcken the Painter revisited

• Le Grande Macabre

• Leslie Megahey’s Bluebeard