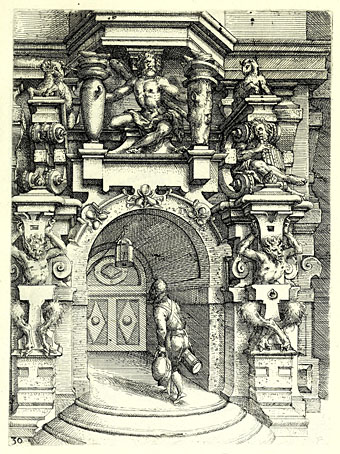

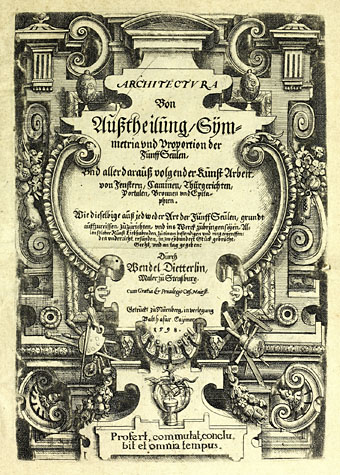

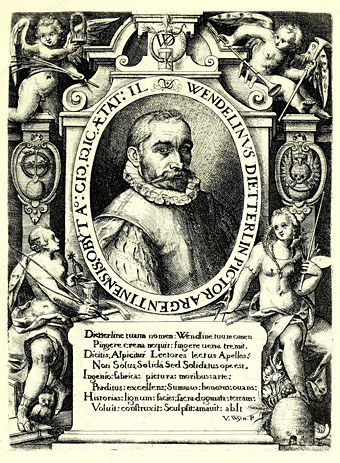

While looking through my bookshelves recently for examples of Baroque architecture I was reminded of the eccentric designs of Wendel Dietterlin (c. 1550–1599), a German painter and engraver whose Architectura (1598) is less a guide to architectural form than an excuse to indulge the artist’s fervid imagination. This wasn’t really the reference material I was after—Dietterlin is pre-Baroque—but I’d not seen so much of his work in one place before. Dover Publications have reprinted all of these plates for many years as The Fantastic Engravings Of Wendel Dietterlin but it’s one Dover book I’ve never owned.

“Fantastic” is an apt description. Where a similar study might present the reader with careful elaborations of Vitruvian principles, Dietterlin offers plate after plate of suggestions for portals, fountains, fireplaces and facades, many of which are festooned with bizarre and grotesque details. Wild animals are a persistent theme. Other artists of the period tended to favour mythological scenes for fountain sculpture; Dietterlin shows a series of large animals being attacked by smaller ones: bear versus dogs, dragon versus men, and so on. Similar groupings may be found on his designs for rustic arches. Ostensibly these are traditional hunting scenes but there’s a fury in Dietterlin’s renderings that pushes the representations away from the decorative towards the pathological.

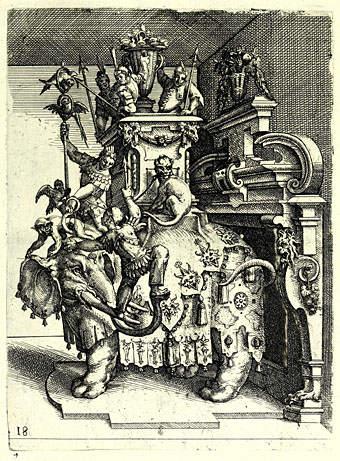

In other designs the wildness is transferred to the decoration itself. Examples of the traditionally sober orders of Classical architecture are shown encrusted with decorations added at the whim of the artist; Dietterlin wasn’t the only artist to do this but other artists are seldom this excessive. Strangest of all is the plate that shows a huge elephant standing before (or emerging from) a fireplace. René Passeron included a handful of engraving artists in the precursors section of his Concise Encyclopedia of Surrealism in 1975, but Dietterlin isn’t among them. I’d say that elephant alone is suitable qualification, a forerunner of Magritte’s Time Transfixed, as well as a literal (if inadvertent) representation of “the elephant in the room”.