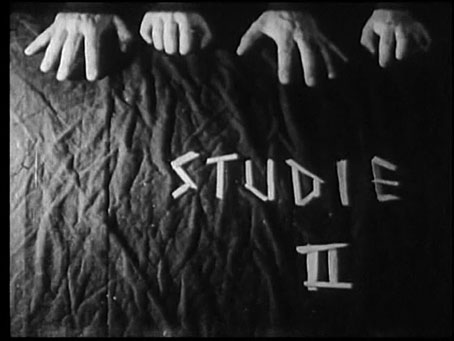

“Almost every time one takes a closer look at a film that is world-famous one has to face the sad fact that the film does not really exist in a form that seems acceptable.” Martin Koerber discussing the physical condition of Vampyr. Carl Dreyer’s film is now 90 years old, and has suffered more than most from the ravages of time and censorship, but after several years of restoration (or should that be resurrection?) by Koerber and others it looks as good today as it’s likely to get; not perfect, when many excisions remain lost, but still the best print I’ve seen.

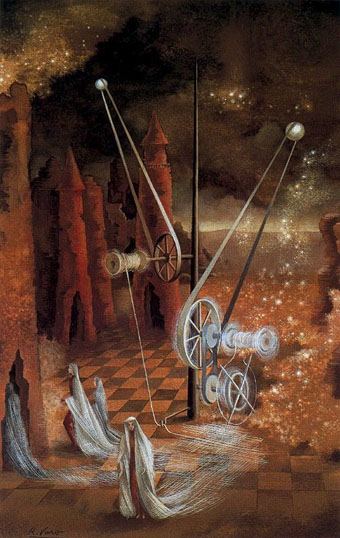

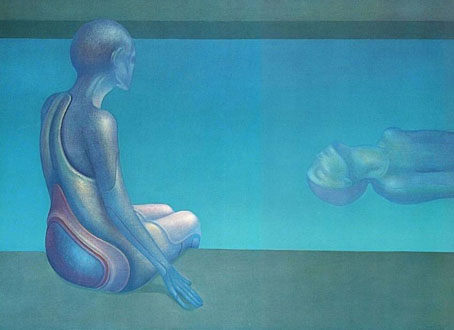

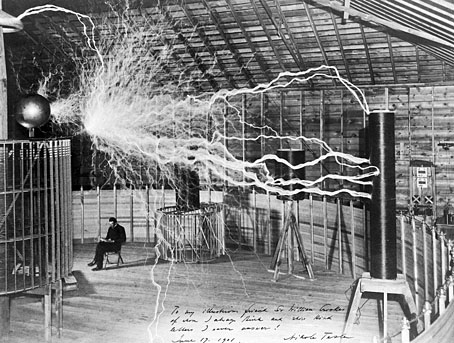

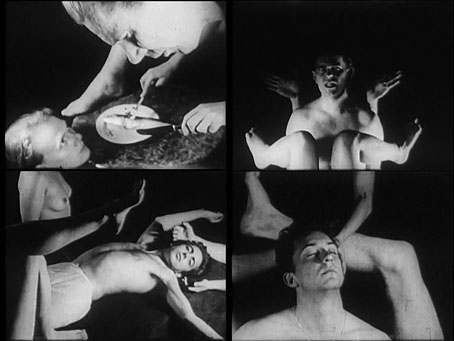

Watching this again I’d forgotten how deeply strange it all is, a sketch of conventional horror motifs borrowed from Sheridan Le Fanu’s In a Glass Darkly, overlaid with inexplicable events from the imaginations of Dreyer and screenwriter Christen Jul. “Surreal” is the word that comes to mind, not least because the film was being shot in locations around Paris while the Surrealists were busy creating their aesthetic scandals inside the city; the Surrealist quest for “the marvellous” and the iconography of dreams is fully realised in Dreyer’s revenants and ambulatory shadows. Vampyr manages to look as primitive as an early silent film—the diffuse photography and stilted acting—while also being sophisticated in its visual style and directorial technique; something else I’d forgotten was the restlessness of Rudolph Maté’s camera, continually moving about the actors or roaming the rooms and corridors. Dreyer’s shoot was almost finished when the Tod Browning version of Dracula was going into production, a film which is equally stilted but with few redeeming features. Where Browning’s film is inert and devoid of atmosphere Vampyr is thoroughly cinematic, with a startling, original score by Wolfgang Zeller that’s nothing like the classical pastiches of Hollywood in the 1930s.

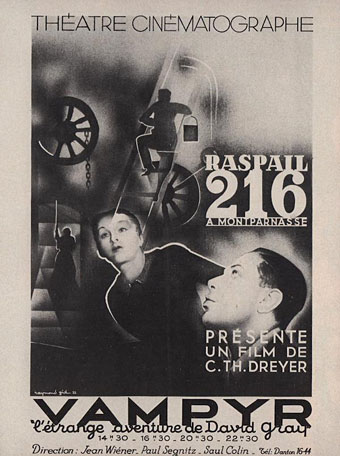

Kim Newman compares Dreyer’s actors to the hypnotised cast of Werner Herzog’s Heart of Glass, an astute observation. I’ve never regarded the somnolent performances as a flaw, not when they suit the mood so well. More of a deficiency is Vampyr‘s title which raises expectations of a traditional tale of the undead that Dreyer never delivers. The English and French versions were originally titled The Strange Adventure of David Gray but it’s the German version that provides most of the materials for the restored print, and this was retitled Vampyr: The Strange Dream of Allan Gray. (The dual name of the central character is another complication.) The distributors held over the release in Germany until Universal’s Dracula and Frankenstein had opened there which must have pressured them to present the film (unsuccessfully as it turned out) as a conventional horror story. “Strange Dream” is evasive but also more accurate. It reminds me of the only description that David Lynch would provide when asked what Eraserhead was all about: “A dream of dark and troubling things”.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Universal horror

• Undead visions

• David Rudkin on Carl Dreyer’s Vampyr