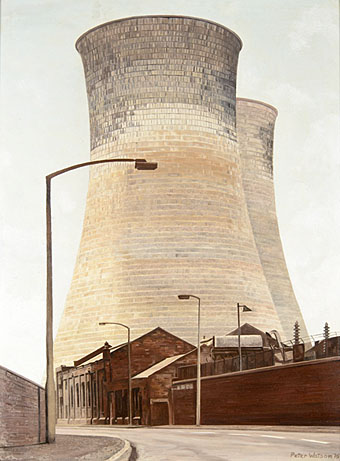

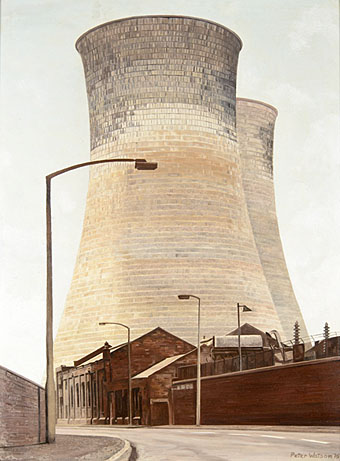

Rawmarsh Road, Rotherham, 1975 by Peter Watson.

• Steel Cathedrals (1985), a composition by David Sylvian (with Ryuichi Sakamoto, Kenny Wheeler, Robert Fripp & others) was originally available only on the cassette release of Sylvian’s Alchemy: An Index Of Possibilities, and a video cassette where the music accompanied views of Japanese industry by Yasuyuki Yamaguchi. The video hasn’t been reissued since but may be viewed here.

• “If, as Arthur C Clarke famously observed, any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic, then can we accept that any sufficiently advanced magic is also indistinguishable from technology?” asks Mark Pilkington.

• “I didn’t like the idea of cartoons as just funny jokes, they had to have some relevant piece of observation in them to do with the society we are living in,” says Ralph Steadman.

I listen to music all the time, and I’ll often seek connections across quite disparate genres of that whatever I’m looking for. Sometimes it’s an aesthetic or a feeling, sometimes a pattern or structure, but it tends to cut across genres. The thing I liked about black metal and doom metal is the slowness and weightiness of it, it’s like deep time but in music. Sunn O))), Xasthur, and other bands captured this black gravity of sound. And they also tend to eschew the traditional vocal-lead guitar set-up, and everything is in the slow-moving wash and texture of sound.

I found that in other genres like noise music (especially Keiji Haino), the European avant-garde with composers like Ligeti, Scelsi, and Dumitrescu, dark ambient artists such as Lustmord or vidnaObmana, and contemporary works like Chihei Hatakeyama’s Too Much Sadness, Rafael Anton Irisarri’s A Fragile Geography, or Christina Vantzou’s No.4. There’s a lot to talk about in terms of music and forms of sorrow or grief, certainly every musical tradition has that—the funeral dirge, requiem, lamentation, or whatever.

Eugene Thacker listing a few favourite musicians and composers during a discussion with Michael Brooks about Thacker’s new book, Infinite Resignation

• The fourth edition of Wyrd Daze—”The multimedia zine of speculative fiction + extra-ordinary music, art & writing”—is out now.

• The Library of Congress has opened its National Screening Room, an online service for viewing films in the library’s collection.

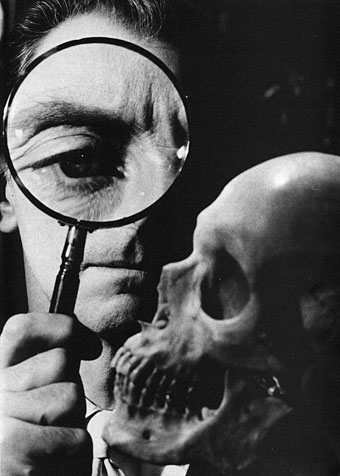

• The London Library discovered some of the books that Bram Stoker used for research when he was writing Dracula.

• “Oscar Wilde’s stock has never been higher,” says John Mullan, reviewing Oscar: A Life by Matthew Sturgis.

• Mixes of the week: RA Podcast 648 by Sarah Davachi, and Secret Thirteen Mix 269 by Sstrom.

• David Lynch directs a video for A Real Indication by Thought Gang.

• “Edward Gorey lived at the ballet,” says his biographer, Mark Dery.

• A new version of Blue Velvet Blues by Acid Mothers Temple.

• Photos of cooling-tower interiors by Reginald Van de Velde.

• Aaron Worth on Arthur Machen: “the HG Wells of horror”.

• The Strange World of…Barry Adamson.

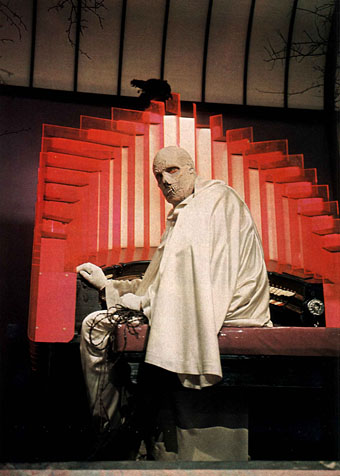

• Glass And Steel No. 1 (1983) by Marc Barreca | Death Is The Beginning (1996) by Steel | Painless Steel (2000) by Bohren & Der Club Of Gore