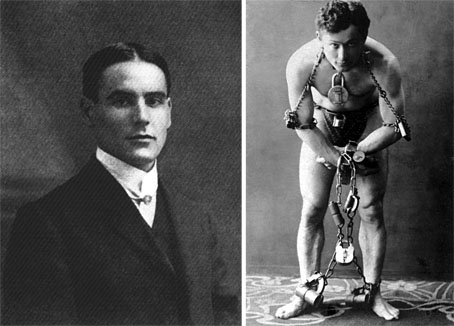

William Hope Hodgson and Harry Houdini.

Work this week has had me scouring the Internet Archive’s scanned books more than usual for source material. You’ll see the fruits of this in due course, but the search turned up a small book from 1922, The Adventurous Life of a Versatile Artist: Houdini, an anonymous account of the escapologist’s career padded out with many newspaper reports of his exploits in various cities. One of these is the notorious meeting between Houdini and writer William Hope Hodgson on the stage of the Palace Theatre, Blackburn, Lancashire, in 1902. Hodgson was still running his School of Physical Culture in the town at this time, and was otherwise unknown. He only began writing the weird fantasy for which he’s celebrated when the school failed and he needed to earn a living some other way.

The following account has been reprinted often enough in collections of Hodgson ephemera but this is the first time I’ve seen it in a Houdini book. Houdini was a hero of mine when I was 12 or 13, not so much for his escapology but for his magic tricks. I had an obsession with stage magic for a while, and had read and re-read JC Cannell’s The Secrets of Houdini (1932), a book which exposed for the first time the workings of Houdini’s tricks and many of his escape acts. It was a surprise after discovering Hodgson’s work to read about the Houdini encounter. Strangest of all is that Hodgson’s books were later championed by HP Lovecraft who ghost-wrote Under the Pyramids (aka Entombed with the Pharaohs or Imprisoned with the Pharaohs) for Houdini, a story published in Weird Tales in 1924. I’ve wondered for years whether Houdini or Lovecraft were aware of this connection. Probably not. Hodgson in 1902 was unknown, and Houdini’s career and fame were such he would have been far too busy to dwell on the matter or care what happened to the diminutive bodybuilder who treated him so badly that evening.

*

AN EPISODE IN HOUDINI’S LIFE.

Star, Blackburn, England, Saturday, Oct. 25, 1902.

MANACLED BY A STRONG MAN.

TRUSSED TILL MIDNIGHT.

Unparalleled Scenes at the Palace Theatre.

Never in the history of Blackburn or music hall life has there been witnessed so remarkable a scene as occurred last night. Houdini, the Handcuff King, and Mr. Hodgson, principal of the School of Physical Culture, provided a big sensation for the patrons of the Palace Theatre, Blackburn.

Houdini, who has been appearing at the Palace during the week, claims to be able to release himself from any of the regulation shackles or irons used by the police of Europe or America, and offered nightly to forfeit £25 if he failed to prove his claim. Mr. Hodgson, of the Physical Culture School, Blackburn,took up the challenge, stipulating that he was to use his own irons and fix them himself. Houdini consented, and deposit the £25 with the editor of the Daily Star.

The trial of skill and strength was fixed to take place last night, and the crowd which came together to witness it crammed the theatre literally from floor to ceiling — even standing room being ultimately unobtainable.

Shortly after ten o’clock the parties to the challenge faced each other, and excitement at once became intense.

Mr. Hodgson produced 6 pairs of heavy irons, furnished with clanking chains and swinging padlocks. These were carefully examined by Houdini, who raised some disappointment and much sympathetic cheering by stating that his claim was that he could escape from “regulation” irons. The “cuffs ” brought by Mr. Hodgson, he said, had been tampered with — the iron being wrapped round with string, the locks altered, and various other expedients adopted to render escape more difficult.

Mr. Hodgson’s answer, given dramatically from the stage,was that he stipulated that he should bring his own irons.

Houdini again protested that Mr. Hodgson was going beyond the challenge, but added that he was quite willing to go on, if only the audience would give him a little time in which to deal with the extra difficulties.

This announcement was greeted with great cheering, and the work of pinioning proceeded.

First, Mr. Hodgson, with the aid of a companion, fixed a pair of irons over Houdini’s upper arm, passing the chain behind his back and pulling it tight, and fixing the elbows close to the sides.

To make assurance doubly sure, he fixed another pair in the same way, and padlocked both behind.

Then, starting with the wrists, he fixed a pair of chained “cuffs” so that the arms, already pulled stiffly behind, were now pulled forward. The pulling and tugging at this stage was so severe — the strong man exercising his strength to some purpose — that Houdini protested that it was no part of the challenge that his arms should be broken.

He also reminded Mr. Hodgson that he was to fix the irons himself.

This led to Mr. Hodgson’s assistant retiring.

Proceeding, Mr. Hodgson fixed a second pair of “cuffs” on the wrists and padlocked both securely, Houdini’s arms being then trussed to his side so securely that escape seemed absolutely impossible.

Still Mr. Hodgson was not finished with him.

Getting Houdini to kneel down, he passed the chain of a pair of heavy leg irons through the chains which bound the arms together at the back. These were fixed to the ankles,and after a second pair had been added, both were locked,and Houdini now seemed absolutely helpless.

A canopy being placed over Houdini in the middle of the stage, the waiting began, and excitement grew visibly every minute.

Meanwhile Mr. Hodgson and others kept strict watch on the movements of Houdini’s wife and brother (Hardeen), who were both on the stage.

At the end of about 15 minutes the canopy was lifted and Houdini was revealed lying on his side, still securely bound.It was at first thought he had fainted, but he soon made it known that all he wished was to be lifted up. This Mr. Hodgson refused to do, at which the now madly excited audience hissed and ” booed ” him for his unfair treatment, and Hardeen lifted his brother to his knees. The curtain of the cabinet was again closed.

Another 20 minutes passed, and again the curtain was lifted. This time Houdini said his arms were bloodless and numb owing to the pressure of the irons, and asked to have them unlocked for a minute so that the circulation could be restored.

Mr. Hodgson’s reply, given amidst howls, was: “This is a contest, not a love match. If you are beaten, give in.”

Great shouting and excited calling followed, which was renewed when Dr. Bradley, after examining Houdini, said his arms were blue, and it was cruelty to keep him chained up as he was any longer.

Still Mr. Hodgson was obdurate, and the struggle proceeded, Houdini again appealing for time.

Fifteen minutes more: Houdini appeared and announced that one hand was free.

This was the signal for terrific cheering, which was continued after the canopy was dropped.

At intervals Houdini now appeared, and announced further progress in his escape; and when, shortly after midnight, he came out with torn clothing and bleeding arms, and threw the last of the shackles on the stage, the vast audience stood up and cheered and cheered, and yelled themselves hoarse to give vent to their overwrought feelings. Men and women hugged each other in mad excitement. Hats, coats, and umbrellas were thrown up into the air, and pandemonium reigned supreme for 15 minutes.

Houdini, when quietness had been restored, said he had been doing the handcuff trick now for 14 years, but never had he been subjected to such brutality as that to which his bleeding arms and wrists gave witness.

When Houdini again obtained a hearing, it was to state that, not only had the irons been altered, but the locks had been plugged.

It was well after midnight when the huge audience left the theatre, and broke up into excited, gesticulating groups.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Weekend links: Hodgson edition

• Druillet meets Hodgson