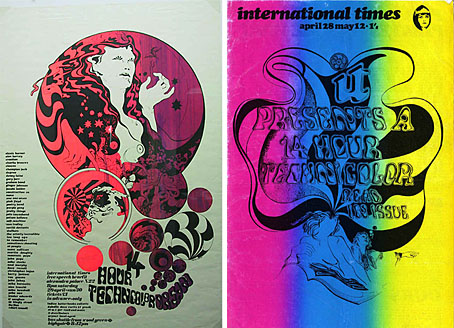

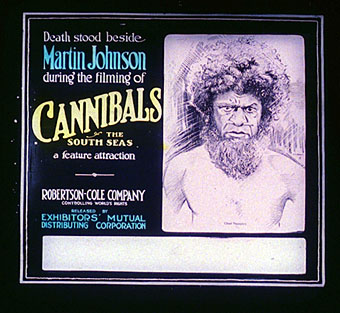

left: event poster by Hapshash & the Coloured Coat.

right: International Times 14-Hour Technicolor Dream special issue, April 1967.

The ICA goes psychedelic, baby. Lucky Londoners get to gorge themselves on this lot next Saturday.

2007 is a year of many anniversaries: twenty years since Acid House, thirty since the release of Never Mind The Bollocks, forty since Sgt. Pepper’s and fifty since the publication of Jack Kerouac’s On The Road.

One event that gets far less publicity, but that was at the heart of everything that came both before and after it also sees its 40th anniversary this year. The 14-Hour Technicolor Dream took place on April the 29th 1967 and was the UK’s first mass-participational all-night psychedelic freakout!

Organised and in a matter of weeks, the event was held in the cavernous confines of Alexandra Palace. The vision of Hoppy Hopkins and Miles, the night saw a glorious mingling of freaks, beats, mods, squares, proto-punks, pop stars and heads come together to dance, trip, love and be.

To celebrate the anniversary, the ICA presents Our Technicolor Dream—a one-off multi-media event that features an array of cult 60s films and animation, full-on psychedelic lightshows, groovy DJs, avant-garde theatre, a Q&A session with the leading lights of the 60s underground and live music with The Amazing World of Arthur Brown, The Pretty Things, Circulus and Mick Farren!

• Tell It Like It Was: The Round Table Speaks: Joe Boyd, Miles, Hoppy Hopkins & John Dunbar.

• Freak Out, Ethel! An Evening of Musical Mayhem: Malcolm Boyle’s play plus The Amazing World of Arthur Brown, Circulus, The Pretty Things and Optikinetics lightshow.

• Boyle Family Films With Music by The Soft Machine

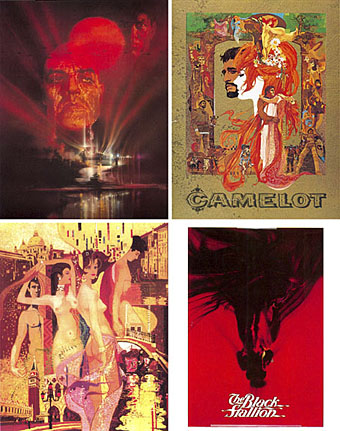

• Weird and Wonderful 60s Animation: Films by Jan Lenica, Jan Svankmajer, Walerian Borowczyk, Chris Marker and Ryan Larkin.

• What’s A Happening? “90 minutes of rare, lost and unseen psychedelic masterpieces”.

Retrospective newspaper features: The Independent | The Times

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Verner Panton’s Visiona II

• The art of Yayoi Kusama

• All you need is…

• Sans Soleil

• Summer of Love Redux

• The Invasion of Thunderbolt Pagoda

• Oz magazine, 1967–73

• Strange Things Are Happening, 1988–1990