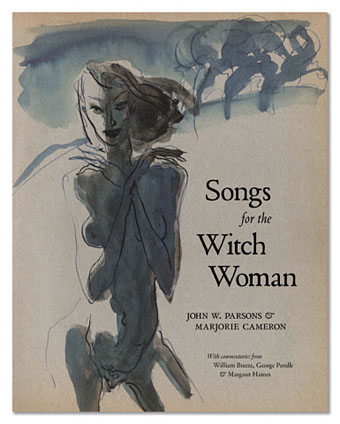

It wasn’t so very long ago that occult artist Marjorie Cameron (1922–1995) was visible only as a silent and enigmatic presence in films by Kenneth Anger and Curtis Harrington. Previous posts here have catalogued the resurrection of interest in her life and work which now includes a book of poems by husband Jack Parsons, embellished by Cameron’s drawings and paintings. This is another quality production from Fulgur Esoterica who provided me with these page layouts. Details of the book follow. See this page at Fulgur for a few more pieces of artwork.

Songs for the Witch Woman

A Romantic Tragedy filled with Magic‘He’ll be back some time. Laughing at you’

Fulgur Esoterica has announced today the publication of a collection of poems by rocket scientist Jack Parsons’ illustrated by his wife and magical partner Marjorie Cameron. The drawings and poetry have been gathered by Cameron after her husband’s death and are here published together for the first time. The book is the first publication to mark 100 years from Parsons’s birth (1914).

Jack Parsons was not only the most influential Californian magician of his day but was also at the heart of the US rocketry programme as one of the founder of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory before his untimely death at the early age of 37. He died in an explosion which was probably an accident but which has also been seen by some as either a result of his ‘Babalon Working’ or, by some occultists, as a direct result of tampering with dark forces.

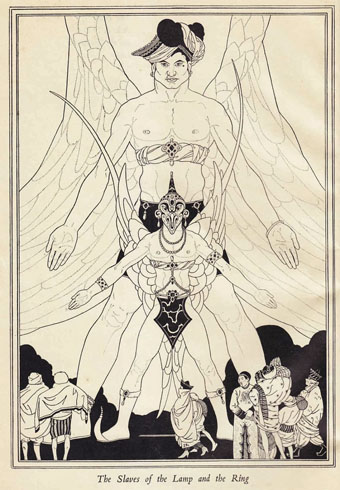

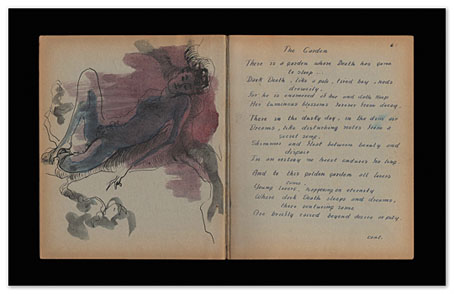

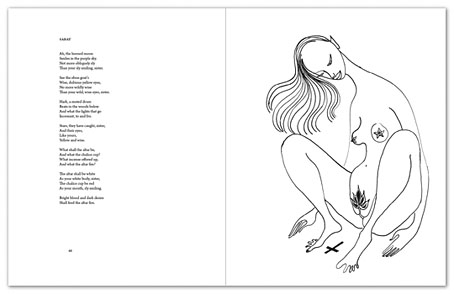

Parsons’s wife Cameron continued to illustrate the poems he wrote for her years after his death. Cameron was an artist and actress who after Parsons’ death moved on to become one of most sought after faces in counter cultural Hollywood circles having appeared in Kenneth Anger’s Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1954) and Curtis Harrington’s Wormwood Star as herself and having figured on the cover of Wallace Berman’s first issue for Semina (1955).

The collaboration presented here creates a unique insight into an intense and unique romantic tragedy. As stated by Parsons’s official biographer and contributor to Songs for the Witch Woman George Pendle, “A collection of uneasy love poems, the language and meter of Songs for the Witch Woman owe a considerable debt to the Romantic poets. Keats’ “Lamia”,

Byron’sBrowning’s “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came”, Tennyson’s “Idylls of the King” are all referred to. […] But nothing is quite what it seems”. He further states that “many of the poems speak of entrapments and reversals, of women tricking or teasing men into their web to be devoured or eaten. And although a rich, pungent sensuousness overlays the poems, with datura and jasmine filling the lines with a somnolent musk, neurosis and fever, worry and sickness, never seem far away. In many ways the poems seem to act as a sort of testing ground for the emotions stirred up by the often masochistic relationship with the fiercely independent Cameron.”The volume is complemented by critical essays and by a diary entry from Cameron’s magical diary. Some say this text constitutes the summoning of a magical entity while others looked at it as an invocation to her lost lover.

Price: Hardback £40. Deluxe £140. Dimensions and info: large format (305mm x 240mm). 176 pages. Premium Italian Paper.

Marjorie Cameron was born in Belle Plaine, Iowa in 1922. The fiery and uncompromising character for which she would later be known manifested from an early age. School friends and teachers alike saw her as a peculiar child who by nature looked at the world from a different angle. After the outbreak of the Second World War Cameron enrolled in the Navy and after a period of training became the cartographer for the Joints Chiefs of Staff. Discharged from the military in 1945, she joined her family in Pasadena where less than a year later she met the man who would change her life.

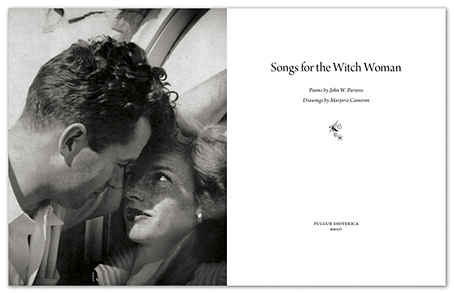

Cameron was twenty-four when she met Jack Parsons, a young and charismatic rocket scientist at the peak of his public career, associate founder of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and acting master of the ‘Agape Lodge of the Ordo Templis Orientis’. For the following seven years Cameron and Parsons worked together in magick, love and art giving birth to one of the most legendary magico-artistic partnerships of the century. Firmly believing that Cameron’s appearance in his life was the result of an intense series of magical workings carried out in the weeks preceding the encounter, Parsons famously wrote to Aleister Crowley ‘I have found my Elemental’. Be it as it may, in the first years of their relationship Cameron was not only unaware of such goings-on but also uninterested in Jack’s spiritual path, preferring art and love over the practice of magic.

But as time went by Parsons assumed another function in Cameron’s life as he quickly became her magical mentor. He renamed her Candida, recommended books, prescribed rituals and meditative practices to deal with her depressions. When Jack Parsons died in an explosion at the age of thirty-seven, Cameron was left alone, wondering whether she was human or elemental.

A very dramatic period follows for Cameron. For a time she withdraws into the desert, where she attempts to connect with the spirit of her lost lover through a series of magical workings. A few years later she comes back to Los Angeles, where in 1954 she appeared in Kenneth Anger’s landmark film Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome. She also met the director Curtis Harrington, for whom she appeared as herself in the short film Wormwood Star. In 1955 she was featured on the cover of the first issue of Wallace Berman’s artistic and literary journal Semina, so marking her firm arrival in the Hollywood artistic counter-culture.

Cameron spent the last decades of her life in West Hollywood, painting, writing and mastering the art of Thai Chi. She died of cancer in 1995 at the age of 73.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• More Cameron

• Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome: The Eldorado Edition

• The Wormwood Star

• Street Fair, 1959

• House of Harrington

• Curtis Harrington, 1926–2007

• The art of Cameron, 1922–1995