More Aubrey Beardsley ephemera. These pages are from the bound edition of The Studio for 1894, reviews of two of Beardsley’s earliest publications: the first editions of Le Morte d’Arthur (which was published in multiple volumes), and the illustrated edition of Oscar Wilde’s Salomé which sealed Beardsley’s reputation as a major force in the art of the 1890s. The reviews lavish praise on both works, unsurprisingly since Beardsley had received the magazine’s support from the very first issue. It’s interesting to note even at this early stage mention of the rumblings of discontent which would grow increasingly loud in the following years. Also that The Peacock Skirt is here given the name The Peacock Girl.

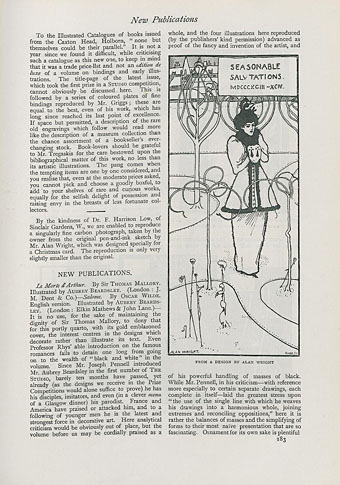

NEW PUBLICATIONS. Le Morte d’Arthur. By Sir Thomas Mallory. Illustrated by Aubrey Beardsley. (London: J. M. Dent & Co.)—Salome. By Oscar Wilde. English version. Illustrated by Aubrey Beardsley. (London: Elkin Mathews & John Lane.)—It is no use, for the sake of maintaining the dignity of Sir Thomas Mallory, to deny that for this portly quarto, with its gold emblazoned cover, the interest centres in the designs which decorate rather than illustrate its text. Even Professor Rhys’ able introduction on the famous romances fails to detain one long from going on to the wealth of “black and white” in the volume. Since Mr. Joseph Pennell introduced Mr. Aubrey Beardsley in the first number of The Studio, barely ten months have passed, yet already (as the designs we receive in the Prize would alone suffice to prove) he has his disciples, imitators, and even (in a clever menu of a Glasgow dinner) his parodist. France and America have praised or attacked him, and to a following of younger men he is the latest and strongest force in decorative art. Here analytical criticism would be obviously out of place, but the volume before us may be cordially praised as a whole, and the four illustrations here reproduced (by the publishers’ kind permission) advanced as proof of the fancy and invention of the artist, and of his powerful handling of masses of black.

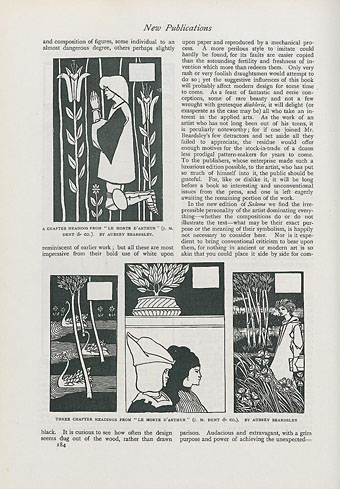

While Mr. Pennell, in his criticism—with reference more especially to certain separate drawings each complete in itself—laid the greatest stress upon “the use of the single line with which he weaves his drawings into a harmonious whole, joining extremes and reconciling oppositions,” here it is rather the balances of masses and the simplifying of forms to their most naive presentation that are so fascinating. Ornament for its own sake is plentiful and composition of figures, some individual to an almost dangerous degree, others perhaps slightly reminiscent of earlier work; but all these are most impressive from their bold use of white upon black. It is curious to see how often the design seems dug out of the wood, rather than drawn upon paper and reproduced by a mechanical process. A more perilous style to imitate could hardly be found, for its faults are easier copied than the astounding fertility and freshness of invention which more than redeem them. Only very rash or very foolish draughtsmen would attempt to do so; yet the suggestive influences of this book will probably affect modern design for some time to come.

As a feast of fantastic and eerie conceptions, some of rare beauty and not a few wrought with grotesque diablerie, it will delight (or exasperate as the case may be) all who take an interest in the applied arts. As the work of an artist who has not long been out of his teens, it is peculiarly noteworthy; for if one joined Mr. Beardsley’s few detractors and set aside all they failed to appreciate, the residue would offer enough motives for the stock-in-trade of a dozen less prodigal pattern-makers for years to come. To the publishers, whose enterprise made such a luxurious edition possible, to the artist, who has put so much of himself into it, the public should be grateful. For, like or dislike it, it will be long before a book so interesting and unconventional issues from the press, and one is left eagerly awaiting the remaining portion of the work.

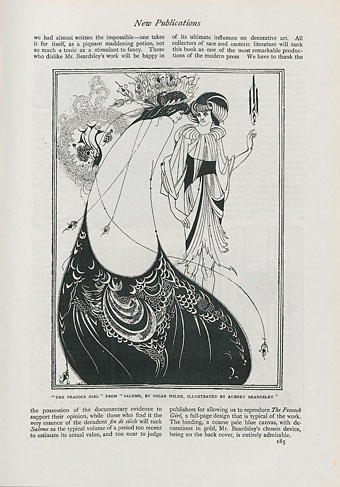

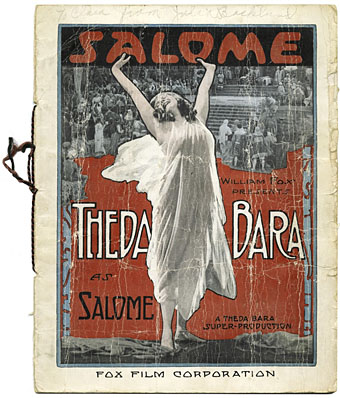

In the new edition of Salome we find the irrepressible personality of the artist dominating everything—whether the compositions do or do not illustrate the text—what may be their exact purpose or the meaning of their symbolism, is happily not necessary to consider here. Nor is it expedient to bring conventional criticism to bear upon them for nothing in ancient or modern art is so akin that you could place it side by side for comparison. Audacious and extravagant, with a grim purpose and power of achieving the unexpected—we had almost written the impossible—one takes it for itself, as a piquant maddening potion, not so much a tonic as a stimulant to fancy. Those who dislike Mr. Beardsley’s work will be happy in the possession of the documentary evidence to support their opinion, while those who find it the very essence of the decadent fin de siècle will rank Salome as the typical volume of a period too recent to estimate its actual value, and too near to judge of its ultimate influence on decorative art. All collectors of rare and esoteric literature will rank this book as one of the most remarkable productions of the modern press. We have to thank the publishers for allowing us to reproduce The Peacock Girl, a full-page design that is typical of the work, The binding, a coarse pale blue canvas, with decorations in gold, Mr. Beardsley’s chosen device, being on the back cover, is entirely admirable.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Aubrey Beardsley archive