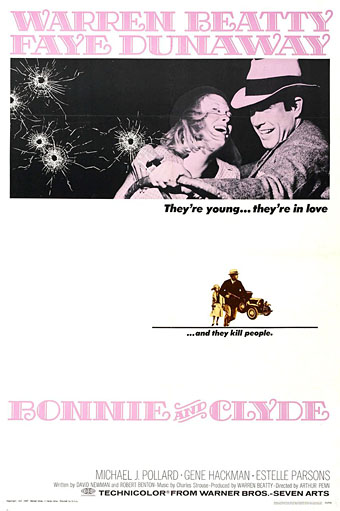

Design by Bill Gold.

With respect to Bonnie and Clyde and my other films, I would have to say that I think violence is a part of the American character. It began with the Western, the frontier. America is a country of people who act out their views in violent ways—there is not a strong tradition of persuasion, of ideation, and of law.

Let’s face it: Kennedy was shot. We’re in Vietnam, shooting people and getting shot. We have not been out of a war for any period of time in my lifetime. Gangsters were flourishing during my youth, I was in the war at age 18, then came Korea, now comes Vietnam. We have a violent society. It’s not Greece, it’s not Athens, it’s not the Renaissance—it is the American society, and I would have to personify it by saying it is a violent one. So why not make films about it.

From The Bonnie and Clyde Book (1972)

Thus film director Arthur Penn, whose death was announced earlier this week, speaking at a press conference in Montreal in 1967 following the first screenings of Bonnie and Clyde. Penn’s film shocked critics and audiences at the time ostensibly for its graphic violence although the disturbance went deeper than that. What I found shocking the first time I saw it—home alone one evening, watching TV with no idea what to expect—was the abrupt shifts of tone from near comedy (the speeding cars and bluegrass soundtrack, Gene Wilder’s role) to awful realism as the consequences of a life of bank-robbing became apparent. This was disturbing for audiences used to being spoon-fed their morality tales with easily identifiable heroes and villains; the sudden, savage conclusion was especially jolting. A “nightmare comedy” quality was a hallmark of Penn’s best work, and he followed Bonnie and Clyde with another nightmare comedy that’s also a further exploration of America’s troubled history, Little Big Man (1970). Here Dustin Hoffman’s character finds himself caught between the Native Americans who raised him and the warring Cavalry intent on massacring the native tribes. Like Robert Aldrich in Ulzana’s Raid (1972), Penn was using Western history to make a statement about America’s involvement in Vietnam; the soldiers in Little Big Man are murderous racists and General Custer is presented not as a doomed hero but as an unhinged psychopath. For me the film has always been distinguished by the character of Little Horse, the first (only?) gay Native American character in cinema. There’s plenty of documentary evidence for gay individuals in Native American tribes but these have seldom been seen in films. It’s Thomas Berger we have to thank for this detail, since it was Berger’s novel which Penn adapted, but the film’s writer and director are also to be congratulated for keeping a minor character who might easily have been excised.

It’s surprising when you see Bonnie and Clyde cited as one of the films that enabled directors to have more artistic freedom during the 1970s that Penn didn’t manage to do more during that golden decade. After Little Big Man there were two films which seem minor in comparison but would be major works from many lesser directors. Night Moves (1975) is one of the handful of attempts at updating film noir which appeared in the 1970s (for others see The Long Goodbye, Robert Aldrich’s Hustle and Taxi Driver), with a screenplay by Alan Sharp, the writer of Ulzana’s Raid. It’s a curio even by the standards of the decade, part detective story set in the Florida Keys, part symbolic drama with chess games and boats named “Point of View”; it’s also Penn’s last great film. The Missouri Breaks (1976), another Western, is fascinating for its pairing of Marlon Brando and Jack Nicholson but Brando’s eccentric performance is the start of his decline as an actor. It’s hard to believe that Penn only made five more films after this but he was one of a number of individual talents who flourished in the 1960s and 1970s then found themselves shut out in the 1980s as intellect was ousted by commerce. There’s even less room for him today than there was then. We’ve travelled from a time of intelligent and challenging films made by adults for adults to an era of shitty action movies and worthless adaptations of equally worthless costumed vigilantes. But I never counsel despair; celebrate what we have rather than bemoaning what we might have lost. Fuck Star Wars in 3D, watch Little Big Man instead.