Whistle and I’ll Come to You (1968).

He blew tentatively and stopped suddenly, startled and yet pleased at the note he had elicited. It had a quality of infinite distance in it, and, soft as it was, he somehow felt it must be audible for miles round. It was a sound, too, that seemed to have the power (which many scents possess) of forming pictures in the brain. He saw quite clearly for a moment a vision of a wide, dark expanse at night, with a fresh wind blowing, and in the midst a lonely figure—how employed, he could not tell. Perhaps he would have seen more had not the picture been broken by the sudden surge of a gust of wind against his casement, so sudden that it made him look up, just in time to see the white glint of a sea-bird’s wing somewhere outside the dark panes.

MR James, Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad.

One of the alleged highlights of this year’s Christmas television from the BBC was a new adaptation of an MR James ghost story, Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad. The film starred John Hurt and came with the same truncated title, Whistle and I’ll Come to You, as was used for Jonathan Miller’s 1968 version, also a BBC production. The story title comes originally from a poem by Robert Burns. The new work was adapted by Neil Cross and directed by Andy de Emmony, and I describe it as an alleged highlight since I wasn’t impressed at all by the drama, the most recent attempt by the BBC to continue a generally creditable tradition of screening ghost stories at Christmas. Before I deal with my disgruntlement I’ll take the opportunity to point the way to some earlier derivations. (And if you don’t want the story spoiled, away and read it first.)

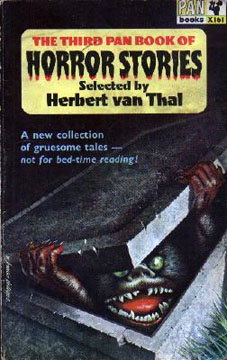

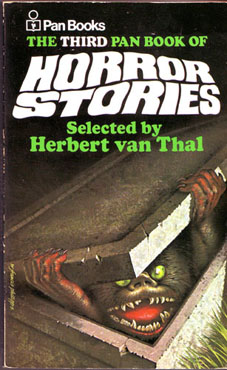

A few years later I was reading the Pan series myself although I never went back to this particular one. Herbert van Thal’s selections got off to a good start, reprinting old horror classics with newer fiction, but soon degenerated into detailed and repetitive tales of dismemberment and blood-letting, the kind of stuff that makes you think “cool” when you’re a teenage boy but which is otherwise worthless. Most of the writers in the later books are unheard of elsewhere which makes me suspect they were probably hacks earning a quick couple of quid writing under pseudonyms. The strangest thing about volume three now is looking at the contents list and seeing that we had stories by William Hope Hodgson and Algernon Blackwood in the house all that time and I never knew it.

A few years later I was reading the Pan series myself although I never went back to this particular one. Herbert van Thal’s selections got off to a good start, reprinting old horror classics with newer fiction, but soon degenerated into detailed and repetitive tales of dismemberment and blood-letting, the kind of stuff that makes you think “cool” when you’re a teenage boy but which is otherwise worthless. Most of the writers in the later books are unheard of elsewhere which makes me suspect they were probably hacks earning a quick couple of quid writing under pseudonyms. The strangest thing about volume three now is looking at the contents list and seeing that we had stories by William Hope Hodgson and Algernon Blackwood in the house all that time and I never knew it.