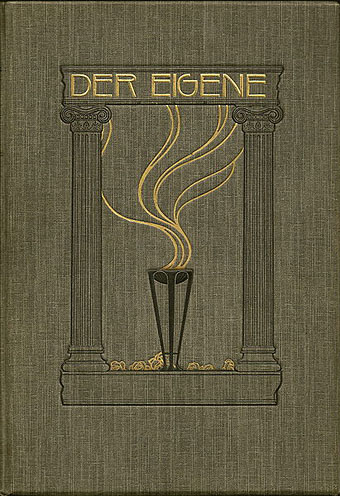

Der Eigene, collected edition, 1906. Design credited to Adolf Brand.

The subtitle is from an article (see below); Der Eigene, the world’s first homosexual periodical was devoted to an ideal of “masculine culture” which looked to Ancient Greece for a model of same-sex relationships. Adolf Brand (“Editor, photographer, poet, polemicist, activist, anarchist, enfant terrible“) founded Der Eigene in Berlin 1896, and to give some idea of how advanced the Germans were in these matters, consider that not only was this a year after Oscar Wilde had been imprisoned in Britain but that Brand’s publication was only the first of several journals advocating gay rights at a time when homosexual acts were still illegal in Germany. The radicalism fell short of including women, unfortunately; like many Grecophile pioneers of the time, Brand’s world had no place for females. All this activity was part of a peculiar ferment in Germany around 1900 which saw the rise of many small groups devoted to naturism, Theosophy, occultism in general, and various pagan revivals. There were also plenty of fiercely nationalist factions, of course, and these took a dim view of Brand’s outspoken homo-anarchism. When the nationalists later turned into the Nazis they destroyed Germany’s nascent gay culture.

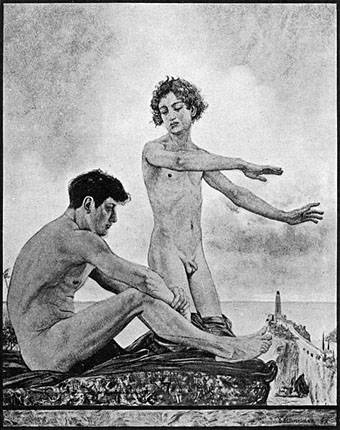

Morgendämmerung (Dawn) by Sascha Schneider, 1897. This drawing also appeared in Jugend magazine the same year.

The pictures here are from sets at Wikimedia Commons where the section devoted to the magazine has finally been amended with some higher-resolution copies. It’s a shame there isn’t more to see given that Der Eigene ran until 1932. I’ll be hoping for further works to come to light as the digitisation of rare publications gathers pace.

Der Eigene, November, 1920.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The gay artists archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Sanctuarium Artis Elisarion

• Jugend Magazine revisited

• The art of Sascha Schneider, 1870–1927

• Hadrian and Greek love