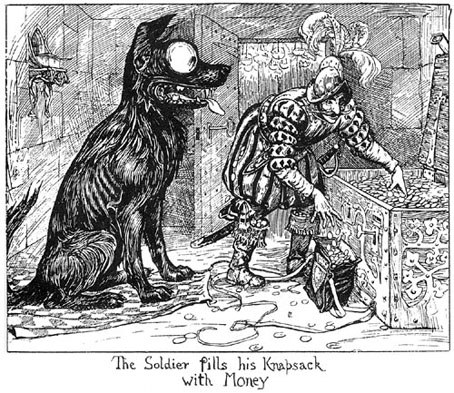

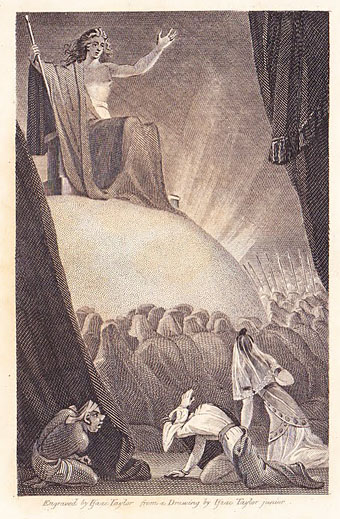

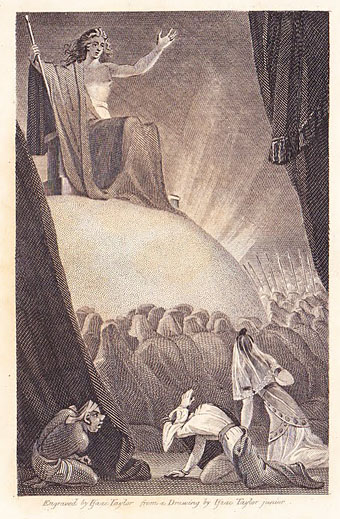

Frontispiece, 1815. Engraved by Isaac Taylor after a drawing by Isaac Taylor Jr.

After some time Vathek and Nouronihar perceived a gleam brightening through the drapery, and entered a vast tabernacle carpeted with the skins of leopards; an infinity of elders with streaming beards, and Afrits in complete armour, had prostrated themselves before the ascent of a lofty eminence, on the top of which, upon a globe of fire, sat the formidable Eblis. His person was that of a young man, whose noble and regular features seemed to have been tarnished by malignant vapours; in his large eyes appeared both pride and despair; his flowing hair retained some resemblance to that of an angel of light; in his hand, which thunder had blasted, he swayed the iron sceptre that causes the monster Ouranabad, the Afrits, and all the powers of the abyss to tremble; at his presence the heart of the Caliph sank within him, and for the first time he fell prostrate on his face.

Vathek by William Beckford

The inevitable follow-up to yesterday’s post. Vathek was, we’re told, written in three days and two nights in the winter of 1782 when William Beckford was only 21. The novel is an Orientalist fantasy that’s grotesque and arabesque in the original sense of those terms, very much influenced by The Arabian Nights and similar tales. Here’s HP Lovecraft with a description:

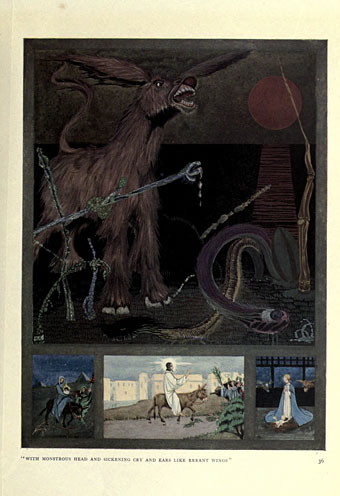

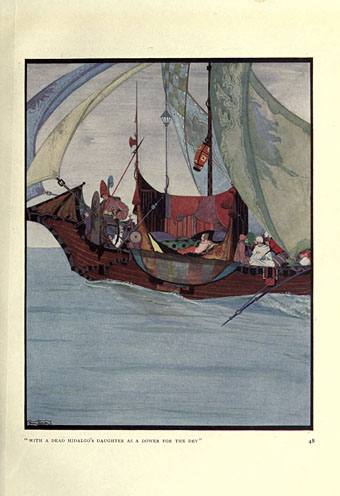

Vathek is a tale of the grandson of the Caliph Haroun, who, tormented by that ambition for super-terrestrial power, pleasure, and learning which animates the average Gothic villain or Byronic hero (essentially cognate types), is lured by an evil genius to seek the subterranean throne of the mighty and fabulous pre-Adamite sultans in the fiery halls of Eblis, the Mahometan Devil. The descriptions of Vathek’s palaces and diversions, of his scheming sorceress-mother Carathis and her witch-tower with the fifty one-eyed negresses, of his pilgrimage to the haunted ruins of Istakhar (Persepolis) and of the impish bride Nouronihar whom he treacherously acquired on the way, of Istakhar’s primordial towers and terraces in the burning moonlight of the waste, and of the terrible Cyclopean halls of Eblis, where, lured by glittering promises, each victim is compelled to wander in anguish forever, his right hand upon his blazingly ignited and eternally burning heart, are triumphs of weird colouring which raise the book to a permanent place in English letters. No less notable are the three Episodes of Vathek, intended for insertion in the tale as narratives of Vathek’s fellow-victims in Eblis’ infernal halls, which remained unpublished throughout the author’s lifetime and were discovered as recently as 1909 by the scholar Lewis Melville whilst collecting material for his Life and Letters of William Beckford. Beckford, however, lacks the essential mysticism which marks the acutest form of the weird; so that his tales have a certain knowing latin hardness and clearness preclusive of sheer panic fright.

Jorge Luis Borges noted some of the influences in his 1943 essay On William Beckford’s Vathek:

…I believe that Vathek foretells, in however rudimentary a way, the satanic splendors of Thomas De Quincey and Poe, of Charles Baudelaire and Huysmans. There is an untranslatable English epithet, “uncanny,” to denote supernatural horror; that epithet (unheimlich in German) is applicable to certain pages of Vathek, but not, as far as I recall, to any other book before it.

[Guy] Chapman notes some of the books that influenced Beckford: the Bibliothéque orientale of Barthélemy d’Herbelot; Hamilton’s Quatre Facardins; Voltaire’s La Princesse de Babylone; the always reviled and admirable Mille et une nuits of Galland. To that list I would add Piranesi’s Carceri d’invenzione: etchings, praised by Beckford, that depict mighty palaces which are also impenetrable labyrinths. Beckford, in the first chapter of Vathek, enumerates five palaces dedicated to the five senses; Marino, in the Adone, had already described five similar gardens.

Byron admired the novel enough to take the name “Giaour” for one of his poems, and it’s no surprise to read that Clark Ashton Smith penned additions to The Third Episode of Vathek. Beckford’s fantasy is very much a precursor of Smith’s equally lurid and sinister stories.

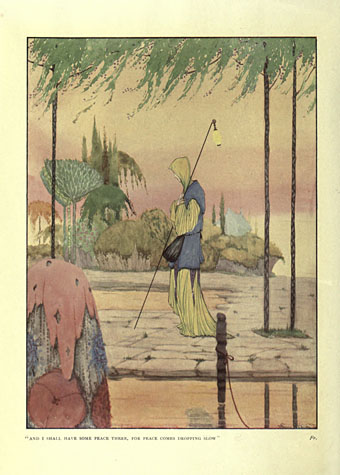

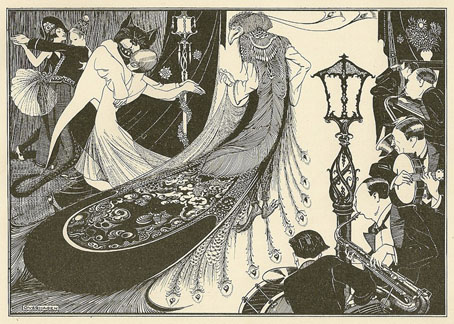

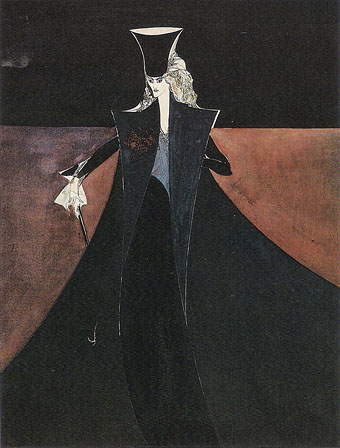

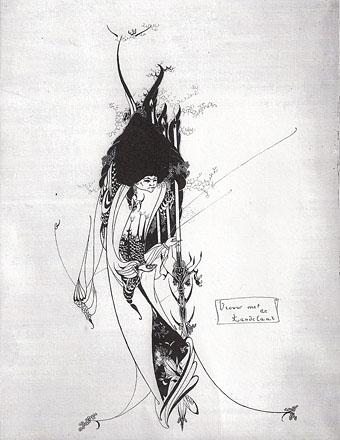

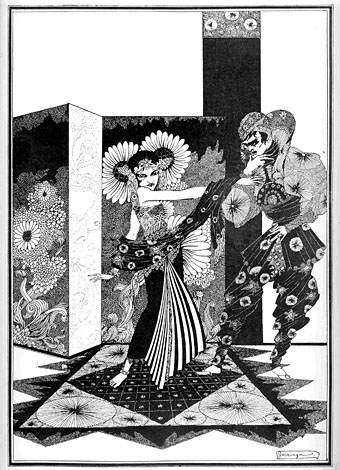

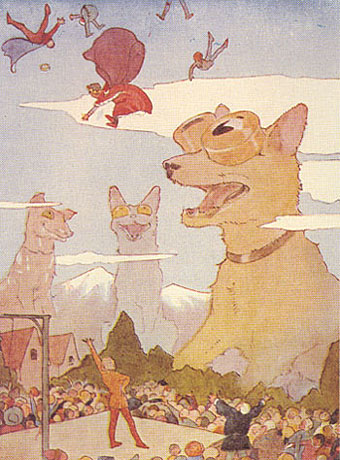

Given all this, it’s a surprise that more illustrators haven’t been attracted to the book. This may in part be a hangover of Victorian prudery: some of the novels of the Gothic period remained shocking to later sensibilities while Beckford’s scandalous reputation (Byron called him “the great Apostle of Paederasty”; to Hilaire Belloc he was “one of the vilest men of his time”) wouldn’t have made his name popular among the collectors of costly illustrated editions. Of the pictures here, the 1815 volume has a frontispiece showing Eblis perched on a hemispherical throne like the one John Martin later gave to Milton’s Satan. More of the uncredited edition from 1923 can be found at the Internet Archive while VTS has plates from the Marion Dorn edition. Mahlon Blaine not only put more effort into his illustrations but the content is also far more suited to his temperament; a shame there aren’t more of the drawings online. And it’s a shame too that Harry Clarke never tackled Beckford’s novel. Many of his contemporaries produced illustrated fairy tale books, as Clarke himself did with Charles Perrault’s stories. But none would have been able to match Clarke if he’d adapted Vathek with the same vigour he brought to Faust.

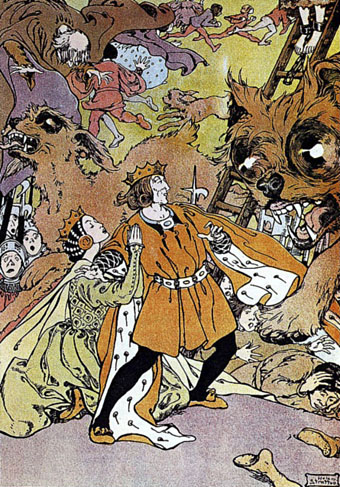

The Caliph and the Giaour (c. 1800) by Richard Westall.

Continue reading “Vathek illustrated”