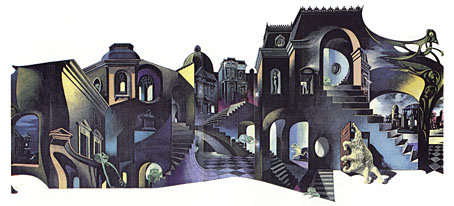

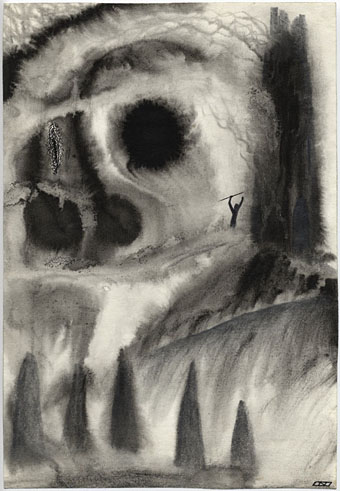

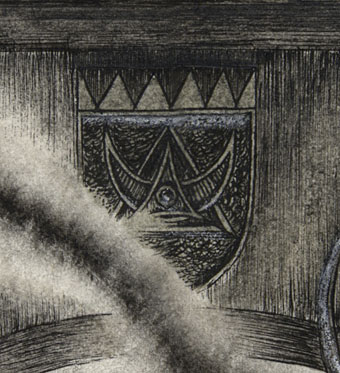

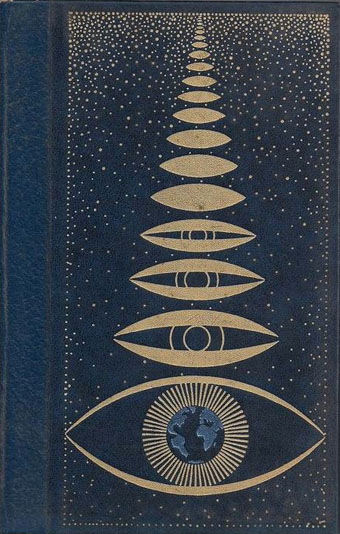

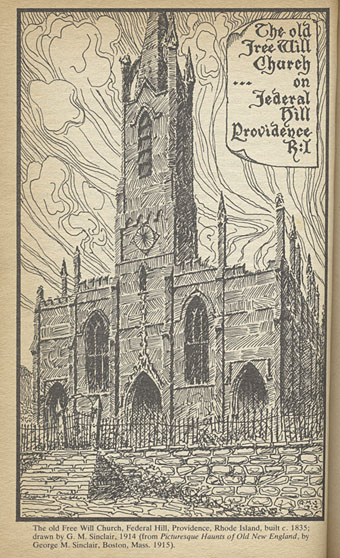

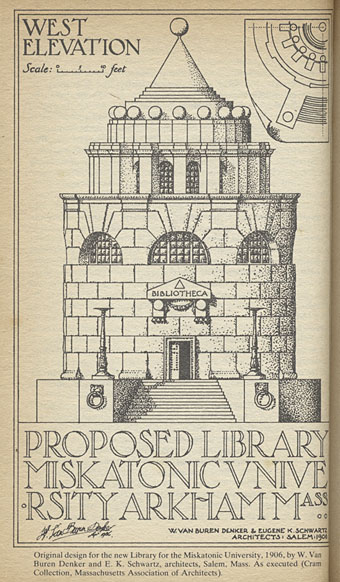

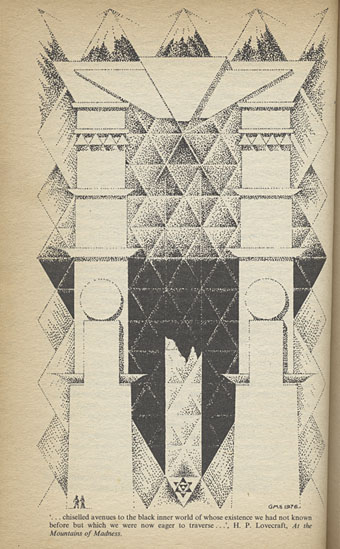

And speaking of architecture… I wouldn’t usually punish the spine of a scarce paperback by subjecting it to trial by flatbed scanner but not all of these drawings have found their way to the web. The artist is Gavin Stamp, here masquerading as “GM Sinclair” for illustrations used in the appendices of the aforementioned Necronomicon (1978), edited by George Hay. The book was published in hardback by occult specialists Neville Spearman, with a paperback following two years later from Corgi Books.

For a purportedly real Necronomicon this one always struck me as more plausible than the US equivalent by Simon; Hay and his collaborators, Robert Turner and David Langford, go to some lengths to describe the sourcing of rare manuscripts from the British Museum, and the process of cryptographic decoding that follows. But the part of the book that made the greatest impression was the essay contributions by Christopher Frayling and Angela Carter, and Gavin Stamp’s accompanying illustrations. In 1980 unless you knew an older book collector (which I didn’t) serious writing about Lovecraft’s work was hard to find. Hay’s book and Stamp’s illustrations were one of several discoveries that pushed me towards illustrating Lovecraft myself.

The pictures above are taken from the paperback while the ones below are lifted from David Langford’s site. I borrowed the pentagonal labyrinth from the title page for the cover of the NecronomiCon convention booklet: two Necronomicons joined, and a nod to a group of writers who helped me along the way.