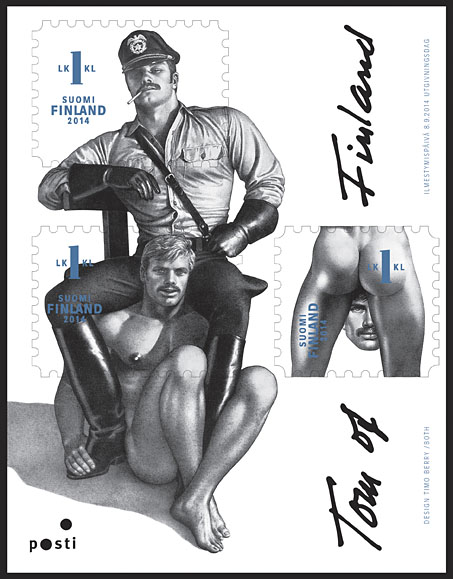

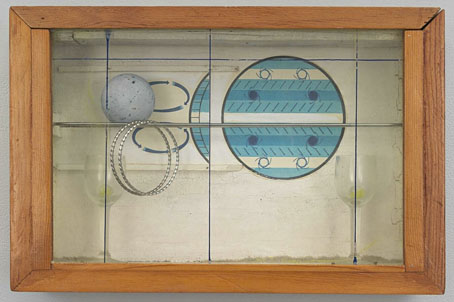

The celebratory stamps produced by the Finnish postal service in 2014.

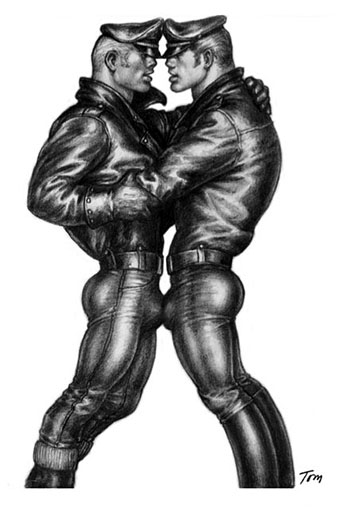

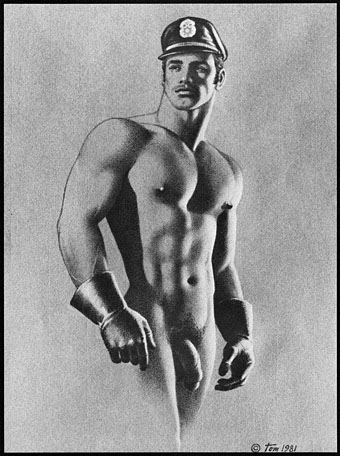

A post for Touko Valio Laaksonen, the man known to the world as Tom of Finland, born 100 years ago today. Back in March I finally acquired Tom of Finland XXL, a gorgeous, heavyweight Taschen volume edited by Dian Hanson, as a result of which Tom and his leather-clad muscle-men have been in my thoughts even without his anniversary. The thick-necked hunks that populate Tom’s drawings have never been my ideal of masculine beauty but I admire his dedication to erotic obsession as well as his draughtsmanship, the latter even more so after seeing the high-quality reproductions in Hanson’s collection. The drawings from the 1970s and 80s are especially impressive, when success had given the artist more time to spend perfecting his figures and capturing all the ways that leather apparel folds itself and reflects the light. His beautiful pencil renderings of jackets, trousers and boots treat their subjects to the careful scrutiny that Dutch still-life painters used to devote to pheasants and apples; this is a fetishist’s infatuation raised to the status of art.

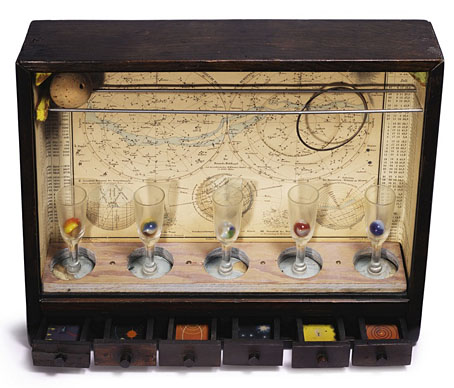

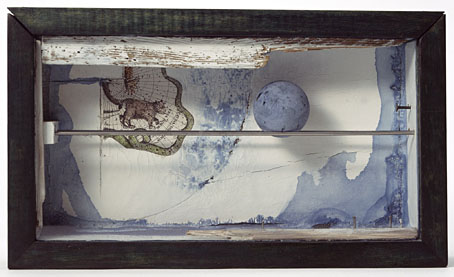

Leather duo (1963).

Tom of Finland’s progress from amateur pornographer to gallery artist and national institution is a very unlikely career path, especially when he wasn’t dependent on the support of the art market. Tom’s earliest drawings and comic strips were relatively simple things but still explicit enough for the Finnish authorities in the 1940s to find them obscene. Many erotic artists have been subject to similar opprobrium but none of them have achieved posthumous fame as the most internationally visible male artist from the nation that once proscribed their work, and all this without toning down that work in any way. Tom shares his celebrity with Moomin creator Tove Jansson, which means that Finland is now the only nation in the world whose art is represented internationally by a gay man and a lesbian. Their work, needless to say, could hardly be more different, despite both artists being adept at black-and-white illustration and the creation of sequential narratives. Jansson’s Moomins have been universally popular for many years but Tom of Finland’s art, which has never been anything other than gay pornography, is inevitably limited in its appeal. The lavish depictions of cock-sucking and anal sex are so profuse and unrelenting that whatever is shown of his drawings in the general media is always carefully selective, shunning the enormous penises in favour of a moustached face or a pair of embracing clones.

I’m amused by this and also reassured that there are still a few aspects of human life that are too anarchic for exploitation by mass media. The global domination of American culture and American technology has rendered everything grist to its all-devouring mill, everything, that is, except for explicit sex. Pornography is also a part of the US cultural behemoth but it’s like the bastard child that everybody pretends doesn’t exist and wishes would go away. America’s gay publications gave Tom of Finland his nom de plume and made him famous, but porn, for a variety of reasons, resists universal acceptance and approval. Tom’s art is so single-minded in its representation of gay men gleefully fucking each other that there’s little about it that can be exploited by cultural products intended to appeal to the widest audience, or sold to nations with repressive attitudes to gay sex and sexuality. Tom’s libidinous leather-clad hero, Kake, ejaculates his way through multiple penetrations and gang bangs the likes of which you’ll never see in a big-budget franchise, no matter how much Hollywood teases audiences with more polite same-sex scenarios. How many erections are a paying audience prepared to swallow?