This is a post I’d been intent on writing for the past four years but kept putting off: why go to great lengths to describe another television drama which people can’t see? And how do you easily appraise something which haunted you for twenty years and which remains a significant obsession? My hand has been forced at last by a forthcoming event (detailed below) so this at least has some fleeting relevance, but before getting to that let’s have some facts.

Penda’s Fen was a TV play first screened in March 1974 in the BBC’s Play For Today strand. It was shot entirely on film (many dramas in the 1970s recorded their interiors on video) and runs for about 90 minutes. The writer was David Rudkin and it was directed by Alan Clarke, a director regarded by many (myself included) as one of the great talents to emerge from British television during the 1960s and 70s. The film was commissioned by David Rose, a producer at the BBC’s Pebble Mill studios in Birmingham, as one of a number of regional dramas. Rudkin was, and still is, an acclaimed playwright and screenwriter whose work is marked by recurrent themes which would include the tensions between pagan spirituality and organized religion, and the emergence of unorthodox sexuality. Both these themes are present in Penda’s Fen, and although the sexuality aspect of his work is important—pioneering, even—he’s far from being a one-note proselytiser. Alan Clarke is renowned today for his later television work which included filmed plays such as Scum (banned by the BBC and re-filmed as a feature), Made in Britain (Tim Roth’s debut piece), The Firm (with Gary Oldman), and Elephant whose title and Steadicam technique were swiped by Gus Van Sant. Penda’s Fen was an early piece for Clarke after which his work became (in Rudkin’s words) “fierce and stark”.

The most ambitious of Alan Clarke’s early projects, Penda’s Fen at first seems a strange choice for him. Most scripts that attracted Clarke, no matter how non-naturalistic, had a gritty, urban feel with springy vernacular dialogue (and sometimes almost no dialogue). David Rudkin’s screenplay is different: rooted in a mystical rural English landscape, it is studded with long, self-consciously poetic speeches and dense with sexual/mythical visions and dreams, theological debate and radical polemic—as well as an analysis of Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius. But though Penda’s Fen is stylistically the odd film out in Clarke’s work, it trumpets many of his favourite themes, in particular what it means to be English in the last quarter of the twentieth century.

Howard Schuman, Sight & Sound, September 1998

Spencer Banks is the principal actor in Penda’s Fen, playing Stephen Franklin, an 18-year-old in his final days at school. The BBC’s Radio Times magazine described the film briefly:

Young Stephen, in the last summer of his boyhood, has somehow awakened a buried force in the landscape around him. It is trying to communicate some warning, a peril he is in; some secret knowledge; some choice he must make, some mission for which he is marked down.

The magazine also interviewed Rudkin about the film:

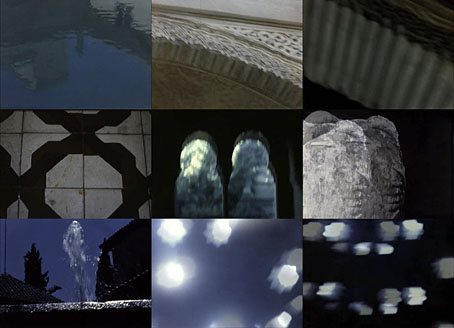

“I think of Penda’s Fen as more a film for television than a TV play—not just because it was shot in real buildings on actual film but because of its visual force…

“It was conceived as a film and written visually. Some people think visual questions are none of the writer’s business—that he should provide the action and leave it to the director to picture it all out. For me, writing for the screen is a business of deciding not only what is to be shown but how it is to be seen…

“Penda’s Fen is a very simple story; it tells of a boy, Stephen, who in the last summer of his boyhood has a series of encounters in the landscape near his home which alter his view of the world…

Continue reading “Penda’s Fen by David Rudkin”