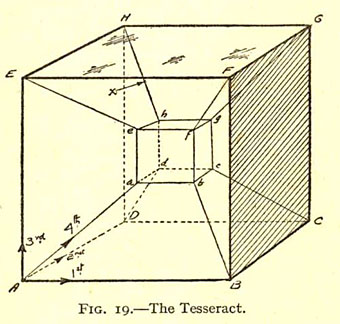

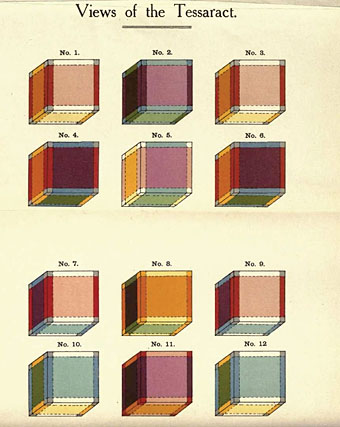

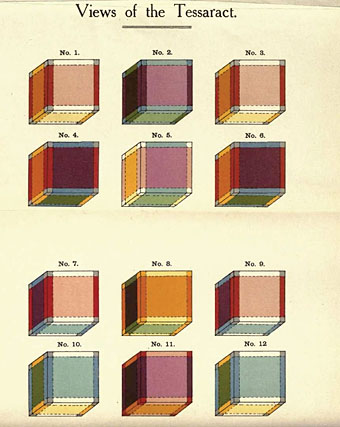

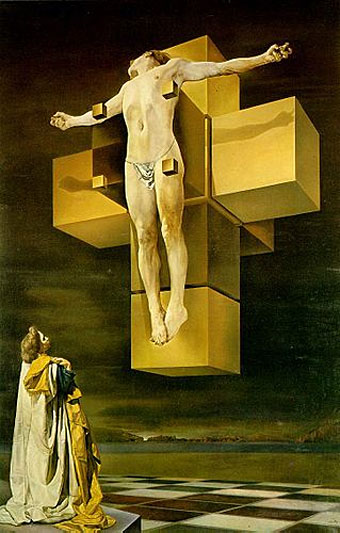

Illustration from The Fourth Dimension (1906) by Charles Howard Hinton.

A slight return to the worlds of Borges. I happened to be re-reading some of the stories in The Book of Sand (1975), one of the later collections which includes the story Borges dedicated to HP Lovecraft, There are more things. Borges’ writings are nothing if not filled with references to other works of literature, philosophies, religions, and ideas in general; following up the less-familiar references would preoccupy a reader to the detriment of the writing so there’s a tendency when reading a Borges piece to take for granted many of those nuggets of esoteric information. I’ve read There are more things many times—it’s a favourite in part for having the additional thrill of Borges going Lovecraftian—but only realised with this reading that I can now fully appreciate the following:

Years later, he was to lend me Hinton’s treatises which attempt to demonstrate the reality of four-dimensional space by means of complicated exercises with multicoloured cubes. I shall never forget the prisms and pyramids that we erected on the floor of his study.

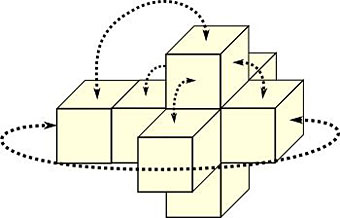

Prior to reading this I did know that Hinton was Charles Howard Hinton (1853–1907), the British mathematician and dimensional theorist. Hinton’s name tends to turn up in discussions of the work of his mystical contemporaries, notably the Theosophists who were more taken with his theories than those in the scientific fields. (A conviction for bigamy didn’t help his reputation.) But those multicoloured cubes were a mystery until the publication of (fittingly) the fourth number of Strange Attractor Journal. Among the usual selection of fascinating articles the book contains a piece by Mark Blacklock about Hinton’s ideas including those mysterious cubes. Drawings of the cubes first appeared in A New Era of Thought (1888) where Hinton proposes using them as aids to a series of mental exercises with which the reader may visualise the higher dimensions of space. Hinton invented the word “tesseract” to describe the four-dimensional structure projected from the faces of his three-dimensional cubes.

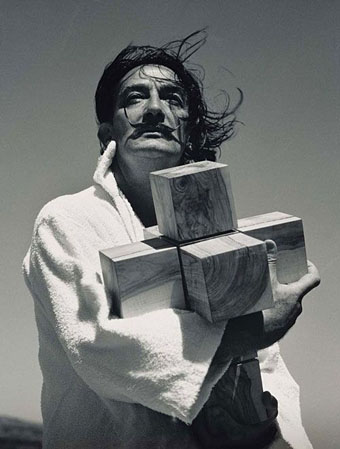

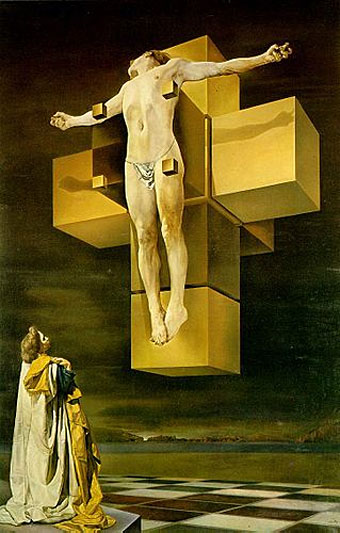

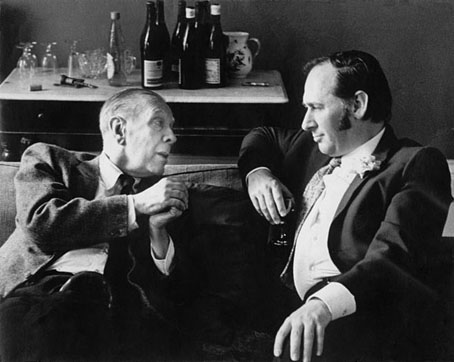

Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus, 1954) by Salvador Dalí.

Hinton may not have impressed his mathematical colleagues as much as he hoped but his ideas have an understandable attraction, as the Borges story demonstrates. The story concerns the refashioning of a Buenos Aires house for an unusual resident; thirty years earlier Robert Heinlein wrote “—And He Built a Crooked House—” in which an architect builds a house in the form of a four-dimensional hypercube: only the lowest cube attached to the ground is visible from the exterior. I read that story when I was a teenager, and was already acquainted with tesseracts thanks to school-friends who were maths whizzes; I was the arts whizz, and I think I was probably the first of us Dalí enthusiasts to discover the artist’s own take on the hypercube, Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus) from 1954. Borges and Heinlein in those stories were both writing their own forms of science fiction, and Dalí’s painting finds itself co-opted into another story with sf connections, The University of Death (1968) by JG Ballard, one of the chapters in The Atrocity Exhibition (1970):

He lit a gold-tipped cigarette, noticing that a photograph of Talbot had been cleverly montaged over a reproduction of Dalí’s ‘Hypercubic Christ’. Even the film festival had been devised as part of the scenario’s calculated psychodrama.

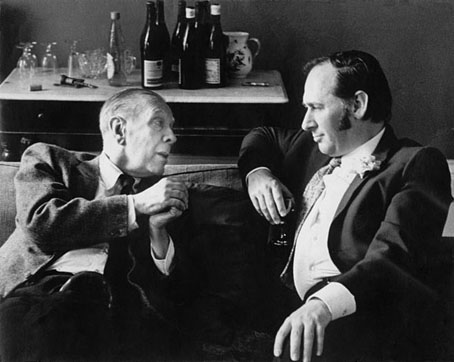

If we seem to have strayed a little then it’s worth noting that Borges was familiar with Ballard’s work: he included The Drowned Giant in the later editions of The Book of Fantasy, the anthology he edited with Adolfo Bioy Casares and Silvina Ocampo. The two writers also met on at least one occasion.

JLB and JGB, circa 1970. Photo by Sophie Baker.

Charles Hinton’s coloured cubes and tesseracts are described in detail in The Fourth Dimension (1906), a reworking of the ideas from A New Era of Thought, and also the source of the colour illustration that everyone reproduces. Mark Blacklock has his own multi-dimensional website where you can read about his construction of a set of three-dimensional Hinton cubes. As for the mental exercises, Blacklock’s piece in Strange Attractor contains an anecdotal warning that the auto-hypnotic system required to fully visualise Hinton’s dimensions can result in a degree of obsession dangerous to the balance of mind. Proceed with caution.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Borges and the cats

• Invasion, a film by Hugo Santiago

• Spiderweb, a film by Paul Miller

• Books Borges never wrote

• Borges and I

• Borges documentary

• Borges in Performance