Ubuweb continues to come up with the very obscure goods. Mary Ellen Bute’s Passages from James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake is the kind of thing you would have been lucky to see on television even in the days when non-Hollywood fare was screened regularly. Joyce is almost the definitive example of the unfilmable author although that didn’t prevent Joseph Strick from having a go at Ulysses in 1967 and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man ten years later. Ulysses if it was filmed at all should probably be done as eighteen hour-long films rather than Strick’s truncated skate through the novel. Some passages work better than others but I’ve never been able to accept Milo O’Shea as Leopold Bloom. Bosco Hogan on the other hand is permanently fixed in my head as Stephen Dedalus having seen Portrait before reading the book.

As to the success of Mary Ellen Bute’s opus, I still haven’t watched it properly so you’ll have to go and look for yourself. It’s little more than an illustrated reading but that’s not necessarily as misguided as it seems. Finnegans Wake for many people is one of English literature’s impregnable fortresses; anything that helps break down the doors is surely worthwhile.

Passages from James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake

Directed by Mary Ellen Bute

Screenplay by Mary Manning

Cinematography by Ted Nemeth

Music by Elliot Kaplan

Cast (in alphabetical order)

Ray Flanagan . . .Young Shem

Peter Haskell . . . Shem

Page Johnson . . . Shaun

Martin J. Kelley . . . Finnegan

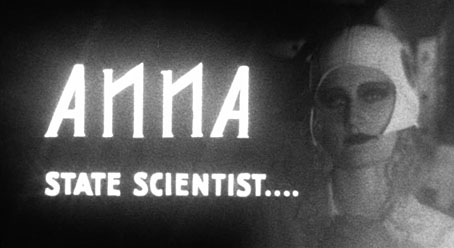

Jane Reilly . . . Anna Livia

There are currently no copies of this film availabe on VHS or DVD; but a 16 mm print is available for museums, universities, and Joycean institutions. Contact Mrs. Cecile Starr at (802) 863-6904; rental is $180.

A half-forgotten, half-legendary pioneer in American abstract and animated filmmaking, Mary Ellen Bute, late in her career as an artist, created this adaptation of James Joyce, her only feature. In the transformation from Joyce’s polyglot prose to the necessarily concrete imagery of actors and sets, Passages discovers a truly oneiric film style, a weirdly post-New Wave rediscovery of Surrealism, and in her panoply of allusion – 1950s dance crazes, atomic weaponry, ICBMs, and television all make appearances – she finds a cinematic approximation of the novel’s nearly impenetrable vertically compressed structure.

With Passages from Finnegans Wake Bute was the first to adapt a work of James Joyce to film and was honored for this project at the Cannes Film Festival in 1965 as best debut.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Wyndham Lewis: Portraits

• Picasso-esque

• Books for Bloomsday

• Finnegan begin again