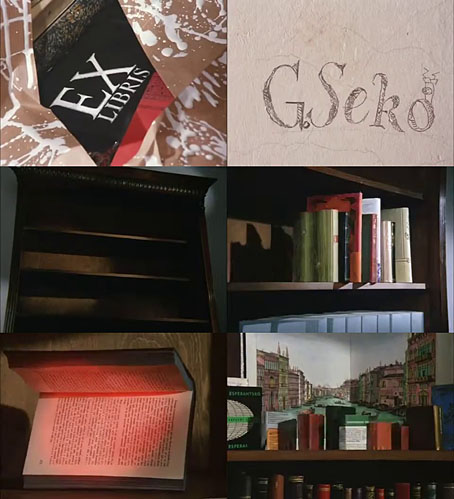

Garik Seko (1935–1994) is an animator whose work I hadn’t encountered before. He was born in Tiflis, Georgia, but worked in Prague where a number of his shorts (this one among them) were made at the Jiří Trnka Studio. Seko’s speciality was the animation of physical objects, in the case of this film a quantity of anthropomorphised books populating the shelves of a bookcase. Jan Švankmajer comes immediately to mind when watching Ex Libris, especially when two philosophy books chew each other to pieces following a vociferous argument. Švankmajer also made films at the Trnka Studio but I’d wary of suggesting an influence in one direction or another when the similarities are superficial ones. Ex Libris was made in 1983, by which time Švankmajer had been animating physical objects (and people) for many years. His own films are more aggressive than Seko’s, usually with a philosophical or Surrealist subtext. Ex Libris may be seen here.

Category: {books}

Books

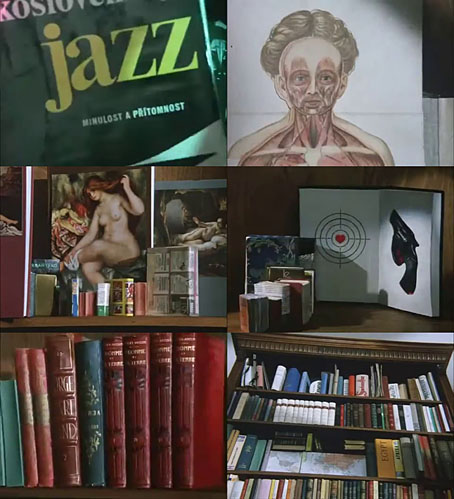

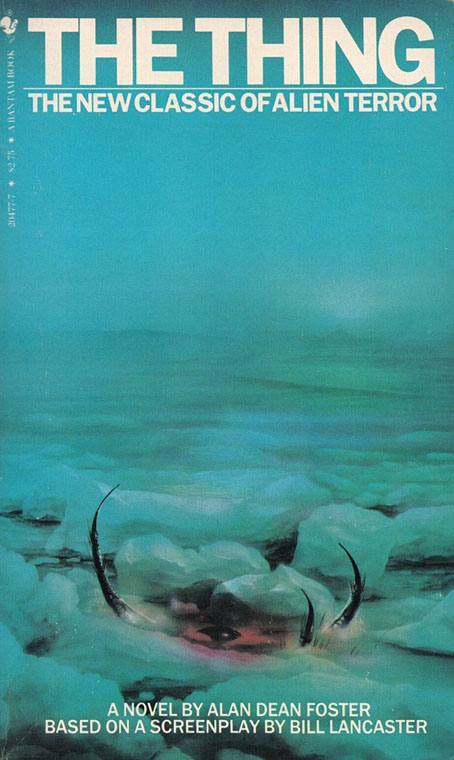

The return of The Thing: Artbook

The most notable feature of the alien organism in John W. Campbell’s “Who Goes There?” is its physical mutability, a quality memorably expressed in John Carpenter’s film adaptation of the story, The Thing. Fitting, then, that The Thing: Artbook is due to be republished later this year in a new edition which adds fresh material to the original volume. I was one of over 350 artists asked to create personal responses to Carpenter’s film in 2016, the results of which were published by Printed In Blood as a heavyweight, large-format hardback. The new book will divide the original into a more manageable two-volume paperback set to which a third volume of fresh material will be added, with all three volumes being contained in a slipcase. The third volume will also be available as a standalone book. Pre-orders may be placed here.

For the reprint there’s the possibility of original contributors doing a new piece, a tempting idea but not something I have the time for at the moment. Last month I started work on a new series of book illustrations which I need to concentrate on even though I wouldn’t mind doing something new based on the film. Before the book was published I guessed that many of the artists would be working variations on favourite scenes or characters, an accurate prediction as it turned out. My own contribution was an attempt to depict some of the moments we don’t see, when transformations are taking place offscreen, but I also had a more complicated, poster-style design in mind which I never managed to work out to my own satisfaction. For now the idea will have to remain frozen in the conceptual ice.

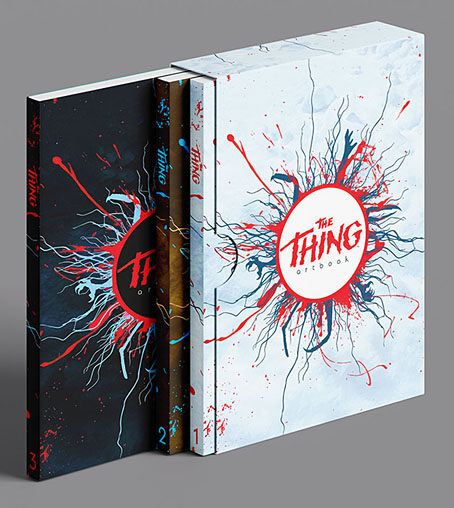

Before starting work on my own drawing I also read John W. Campbell’s story and looked for earlier depictions of his alien. One of the book covers that turned up was the Bantam paperback of Alan Dean Foster’s novelisation (above), a book with a better cover than the UK editions which recycled elements from the film posters. I couldn’t find an artist credit at the time but the cover art is by Jim Burns, a British illustrator best known for his depictions of spacecraft and futuristic technology. Looking for confirmation of his credit turned up a picture of the original painting which has a husky looking at the frozen alien. I can see why the art director wanted the dog removed—the cover is better with all the viewer’s attention drawn to those insectile legs—but Burns’ colour scheme is spoiled by the greenish tinge of the printed version. Ice is a difficult substance to paint well. If I was Burns I would have been a little annoyed that all those icy details had been lost.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Thing: Artbook

• The Thing Group Art Show

• Things

Weekend links 813

Dwellers of the Sea (1962) by Eugene Von Bruenchenhein.

• Among the new titles at Standard Ebooks, the home of free, high-quality, public-domain texts: Conan Stories by Robert E. Howard.

• At Colossal: “Uncanny personalities appear from nature in Malene Hartmann Rasmussen’s ceramics.”

• New music: Glory Black by Sunn O))); Through Lands Of Ghosts by Foster Neville; Sirenoscape by NIMF.

If we insist that art functions as a tool for promoting a limited set of political principles, what happens when an ideology that doesn’t share our values sweeps into power? Learning to engage with complexity is a necessary skill if we are ever to drag ourselves out of the puerile swamp of the culture wars. But if we continue to reduce art to moralistic soundbites, we will only succeed in stripping it of its capacity to transform us, which would be a huge loss. Art can help us to better understand ourselves, and the world we live in, by expressing those things that words cannot. It exposes us to a vast range of experiences, and asks us to sit with the fundamental ambivalences, moral complexities and conflicting emotions that are a part and parcel of being human.

Rosanna McLaughlin on attempts to make art of the past reflect the moral platitudes of the present

• Strange Attractor is having a winter sale with 30% off all its available titles.

• At the BFI: Miriam Balanescu selects 10 great filmmaker biopics.

• Mix of the week: DreamScenes – January 2026 at Ambientblog.

• The Strange World of…Free Jazz & Improvised Music.

• Free (1991) by Mazzy Star | The Free Design (1999) by Stereolab | Everything Is Free (2001) by Gillian Welch

Edmund Dulac’s Princesse Badourah

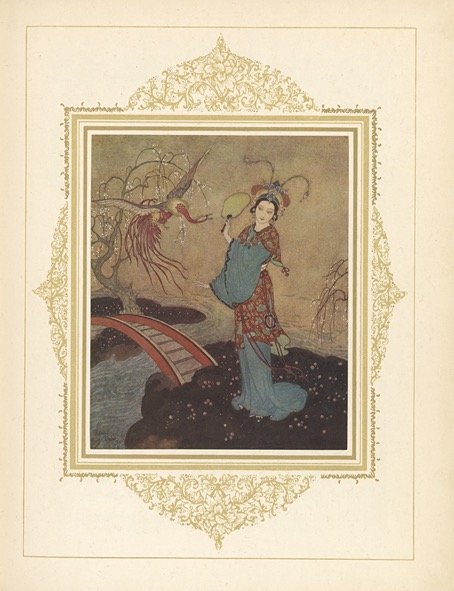

The Chinese princess is usually named Badoura in English editions of The Thousand and One Nights but this volume is a French book which reprints the art that Edmund Dulac created for a retelling of the story by Laurence Housman published in 1913. The English edition was itself a recycled volume, expanded from an earlier Housman/Dulac collection, Stories from the Arabian Nights (1907). The story itself reads like an odd mirroring of some of the versions of Aladdin which end with the triumphant hero marrying a Chinese princess named Badroulbadour. The male character in Princess Badoura is Camaralzaman, the shy son of an Arabian king whose repudiation of women causes his father to throw him into a dungeon. As in Aladdin, a genie helps engineer events to bring the story to a happy resolution.

Some of the art may be recycled but the book design is better than the English editions, with gold frames embracing the tipped-in colour plates. The paintings are consequently reduced in size but this doesn’t harm them too much. One thing the book doesn’t contain is any clue to the writer of the text. I’d guess it was a translation of the Housman version but it could equally be a French retelling taken from another edition altogether.

Weekend links 812

• RIP Béla Tarr. I came late to Tarr’s films, he’d retired from directing by the time I worked my way through most of his oeuvre in 2019. As I’m always saying: better late than never. What I never expected from reading reviews was the irreducible strangeness at the heart of the later films, as well as their meticulous construction. With regard to the latter, mention should be made of the director’s regular collaborators: Ágnes Hranitzky (wife, editor and co-director), László Krasznahorkai (writer), and Mihály Víg (composer).

More Tarr: “The whole fucking storytelling thing is everywhere the same. That’s why I decided I have to do my movies.” Tarr talking to R. Emmet Sweeney in 2012; and at Criterion, Béla Tarr: Lamentation and Laughter by David Hudson.

• “When [Fela Kuti] first saw Lemi Ghariokwu’s work, he said, ‘Wow!’ Then he plied him with marijuana and asked him to design his album sleeves. The artist recalls their extraordinary partnership – and the day Kuti’s Lagos HQ burned.”

• At Smithsonan Mag: “Hundreds of mysterious Victorian-era shoes are washing up on a beach in Wales. Nobody knows where they came from.”

• At Ultrawolvesunderthefullmoon: The collage art of Wilfried Sätty.

• At the BFI: Leigh Singer selects 10 great Lynchian films.

• At Unquiet Things: The vast luminous art of Andy Kehoe.

• At Dennis Cooper’s it’s another Jan Švankmajer Day.

• New music: Light Self All Others by Tarotplane.

• At I Love Typography: Heart-shaped books.

• At Colossal: Luftwerk.

• Sailin’ Shoes (1972) by Van Dyke Parks | Dead Man’s Shoes (1985) by Cabaret Voltaire | New Shoes (2007) by Angelo Badalamenti.