Le Faune (1923) by Carlos Schwabe.

• “When I recently attended a conference in China, many of the presenters left their papers on the cloud—Google Docs, to be specific. You know how this story ends: they got to China and there was no Google. Shit out of luck. Their cloud-based Gmail was also unavailable, as were the cloud lockers on which they had stored their rich media presentations.” Ubuweb’s Kenneth Goldsmith on why he doesn’t trust the Cloud.

• “I’m a poet and Britain is not a land for poets anymore.” A marvellous interview with the great Lindsay Kemp at Dangerous Minds. Subjects include all that you’d hope for: Genet, Salomé, David Bowie, Ken Russell, Derek Jarman, The Wicker Man and “papier maché giant cocks”.

• “As early as the 1950s, Maurice Richardson wrote a Freudian analysis which concluded that Dracula was ‘a kind of incestuous-necrophilious, oral-anal-sadistic all-in wrestling match’.” Christopher Frayling on the Bram Stoker centenary.

• Björk gets enthused by (among other things) Leonora Carrington, The Hourglass Sanatorium and Alejandro Jodorowsky’s YouTube lectures.

• Before Fritz Lang’s Metropolis there was Algol – Tragödie der Macht (1920). Strange Flowers investigates.

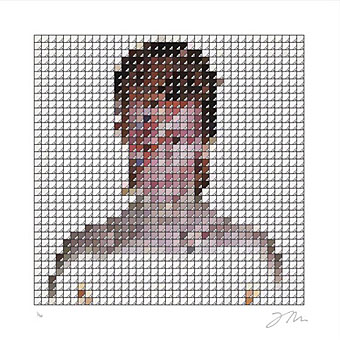

David Marsh recreates famous album covers using Adobe Illustrator’s Pantone swatches.

• New titles forthcoming from Strange Attractor Press. Related: an interview with SAP allies Cyclobe.

• 960 individual slabs of vinyl make an animated waveform for Benga’s I Will Never Change.

• An exhibition of works by Stanislav Szukalksi at Varnish Fine Art, San Francisco,

• Keith Haring‘s erotic mural for the NYC LGBT Community Center is restored.

• The Situationist Times (1962–1967) is resurrected at Boo-Hooray.

• Doors Closing Slowly: Derek Raymond‘s Factory Novels.

• Will Wilkinson insists that fiction isn’t good for you.

• More bookplates at BibliOdyssey and 50 Watts.

• The Top 25 Psychedelic Videos of All Time.

• Flannery O’Connor: cartoonist.

• RIP Adam Yauch.

• Their finest moment: Sabotage (1994) by Beastie Boys.