Rammellzee.

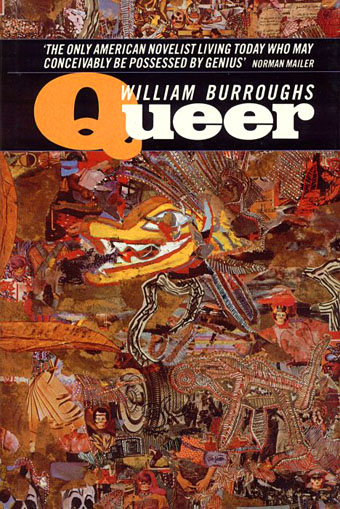

I consider that immortality is the only goal worth striving for: immortality in space. Man is an artefact created for space travel.

William Burroughs, 1982We have to leave this tasteless mould of a planet.

Rammellzee, 2004

It’s fitting that a post about the late Rammellzee should follow one about Brion Gysin even if the circumstances aren’t those one would wish. Before he was involved in music Rammellzee was a graffiti artist and the convoluted mythologising which he later wove around the art of the graffiti tag—and his obsession with words and their meaning—bears comparison with Gysin and Burroughs’ similar mythologising, their theories about the viral origins of language. Look at Gysin’s calligraphic paintings (which he based on Arabic script) and you’ll see an exact analogue with the stylisations of graffiti taggers.

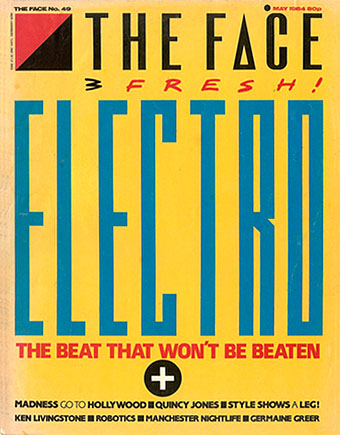

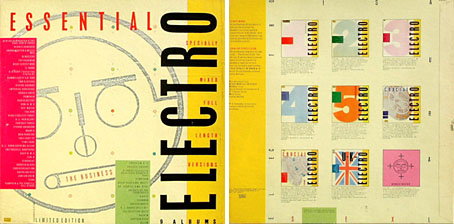

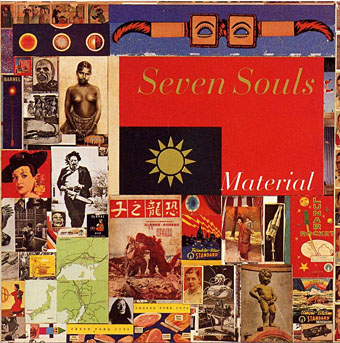

Given all of that, it’s even more fitting that Rammellzee was one of the voices chosen by Bill Laswell to set beside William Burroughs on Material’s finest forty minutes, Seven Souls, in 1989. I knew that voice from the great 1983 single he made with K-Rob, Beat Bop, one of many highlights on the best of the Street Sounds compilations, Electro 2, so it was a pleasant surprise finding it on the album which remains the best musical work that Burroughs was involved with. Rammellzee’s subsequent recordings with Laswell and others evolved an elaborate strain of what’s now known as Afrofuturism which he extended into paintings, collages and sculptural work. When you look at his detailed, science fiction philosophies, or at the underwater mythologies of Drexciya, it’s evident that there’s a rich seam of the African-American imagination which exactly parallels Burroughs’ visionary work. Visionaries right now are in short supply; we can’t afford to lose another.

• Rammellzee: The Remanipulator versus Syntactical Virus by Peter Shapiro (1997)

• No Guts No Galaxy—Rammellzee & phonosycographDISK (1999)

• Rammellzee: The Ikonoklast Samurai by Greg Tate (2004)

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Street Sounds Electro

• The art of Shinro Ohtake