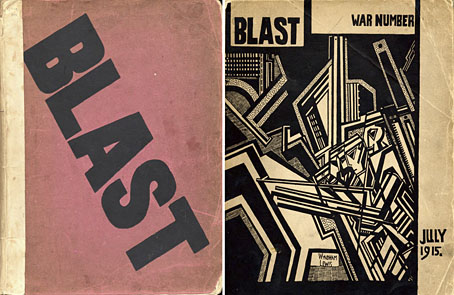

Both issues of Wyndham Lewis’s avant garde art and literature journal can be found in a collection of similar publications from the Modernist years at Brown University here and here. I’ve always liked the bold graphics of Lewis and his fellow Vorticists, and BLAST 2, “the War Number”, is especially good in that regard. The MJP site reminds us that BLAST is still under copyright control outside the US and is also available in facsimile editions from Gingko Press.

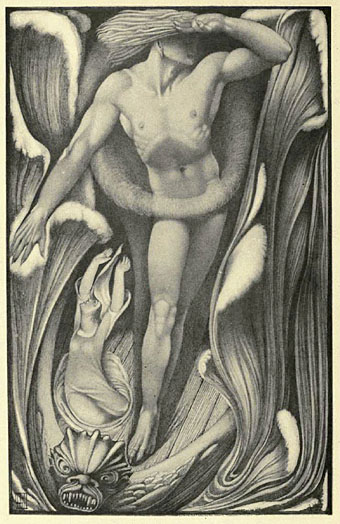

BLAST was the quintessential modernist little magazine. Founded by Wyndham Lewis, with the assistance of Ezra Pound, it ran for just two issues, published in 1914 and 1915. The First World War killed it, along with some of its key contributors. Its purpose was to promote a new movement in literature and visual art, christened Vorticism by Pound and Lewis. Unlike its immediate predecessors and rivals, Vorticism was English, rather than French or Italian, but its dogmas emerged from Imagism in literature and Cubism plus Futurism in visual art.

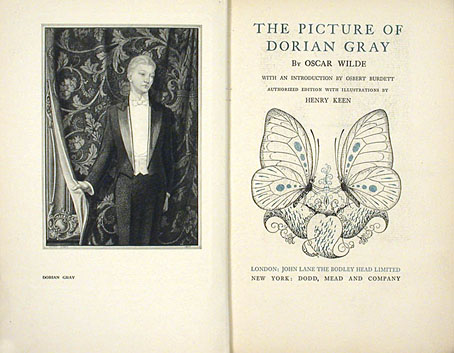

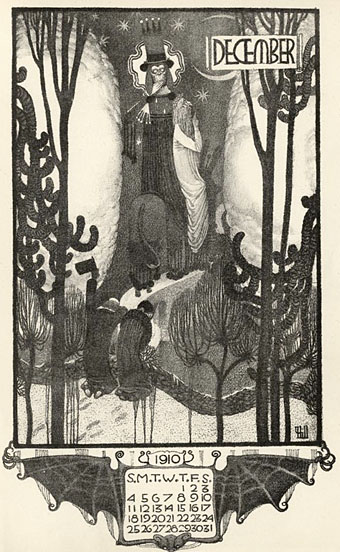

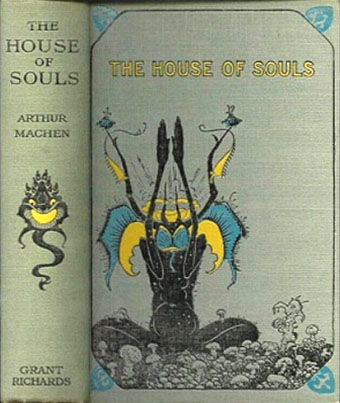

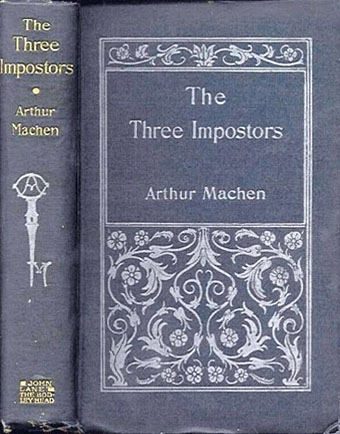

The original BLAST was published by Aubrey Beardsley’s first publisher, John Lane, and it’s fascinating to see Lane advertising back issues of The Yellow Book in pages which include Lewis’s anti-Victorian polemic. Meanwhile I’m still waiting for copies of the Art Nouveau journal Ver Sacrum to turn up somewhere. If anyone runs across quality scans, please leave a comment.

Via Things Magazine.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Wyndham Lewis: Portraits