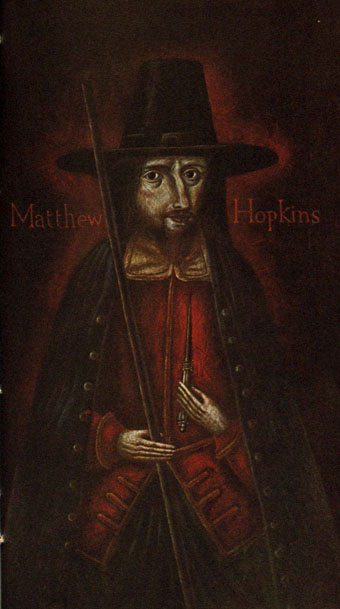

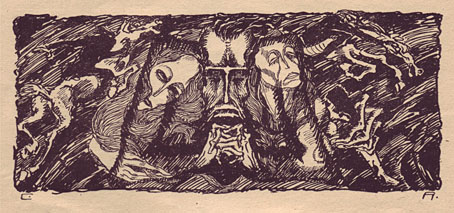

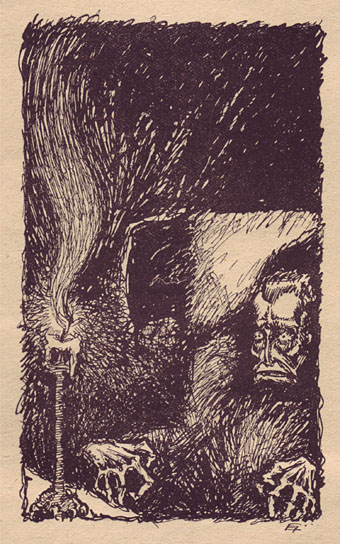

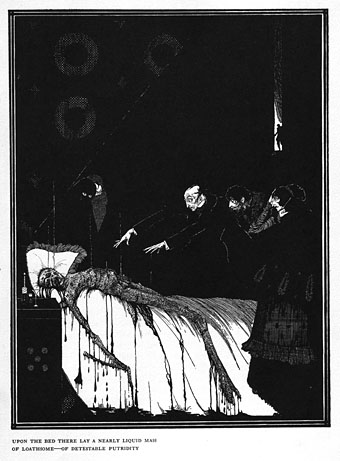

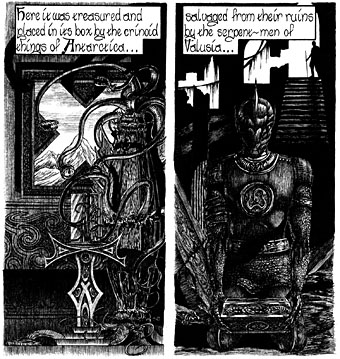

Also witch-finders, demons, magi, and a skeletal Adolf Hitler clutching a glowing crystal ball… Jan Parker is a British artist who was working as an illustrator in the early 1970s, during which time he produced a small number of covers for SF and fantasy titles. One of these, The Worlds of Frank Herbert, is a book I used to see a lot on the secondhand shelves although I never owned a copy. As with Victor Valla’s cover art, the 70s was a decade when idiosyncratic imagery of the type created by Parker and co. was a more common sight on genre covers than it is today. Witchcraft and Black Magic, published by Hamlyn in 1971, brought Parker’s brand of naïve weirdness to a Peter Haining history of the more lurid forms of occultism. This is a book that I did own for a while until someone borrowed it and never returned it, a persistent hazard for the books in my not-very-extensive occult library. Haining’s study is the kind of thing that publishers often call a pocket guide, although this suggests something you’d carry around to be used as an identification tool during chance encounters; you wouldn’t want to encounter most of the people (never mind the creatures) in these paintings.

A handful of Parker’s illustrations turned up some years ago at the now-defunct Front Free Endpaper, then were reblogged at Monster Brains and elsewhere. The copies here are from another recent upload at the Internet Archive where the book is part of a sub-archive of titles scanned from Indian libraries. The very tight binding evidently presented difficulties for the scanner, hence the appearance of fingers holding open most of the pages. It’s good to see this one again; I always valued the book more for the artwork than the text which isn’t bad but was simply another commission for the very prolific Haining, a writer who was a better anthologist than a historian. If you want a general history of the occult there are more authoritative options elsewhere.

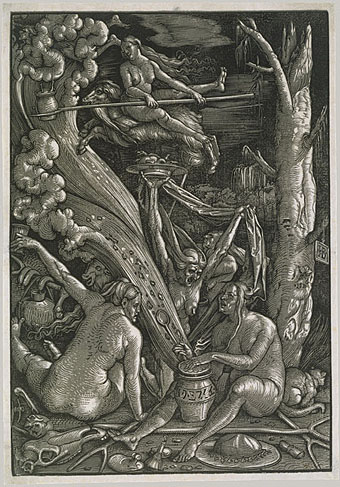

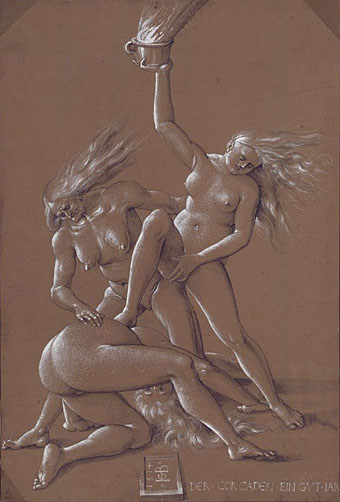

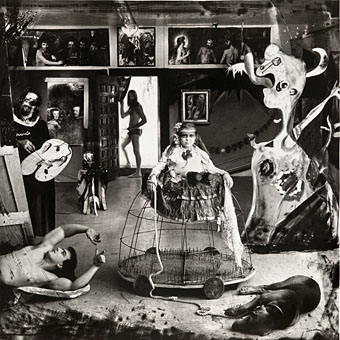

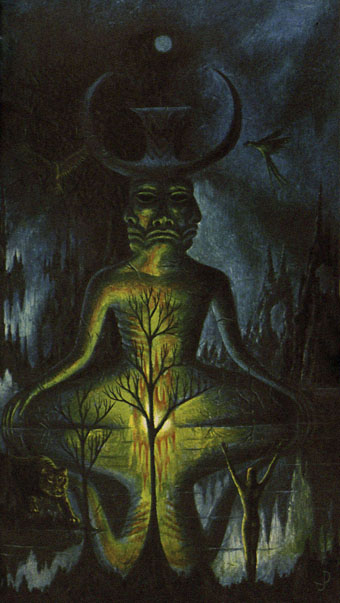

As for the artwork, I wonder now how long it took Parker to paint all these pictures. There are about 80 original illustrations plus a number of others taken from antique books or from artists such as Frans Hals and Goya; that’s a lot of original art for a book of only 160 pages. Many of Parker’s pieces are copies of pre-existing portraits or of familiar illustrations like the perennially popular demons from de Plancy’s Dictionnaire Infernal. This makes me wonder why Hamlyn commissioned copies from Parker rather than simply paying a picture library for the original images as Marshall Cavendish were doing in 1971 with their multi-part encyclopedia, Man, Myth and Magic. Whatever the reason I’m pleased they gave Parker so much free reign. His depictions of historical figures wouldn’t be out of place in the portrait gallery in Dance of the Vampires, while some of his other pieces stray into outright Surrealism; the picture of people being menaced by flying eyeballs was used for the cover art of the US reprint from Bantam.

Haining’s book had at least one reprint in the UK before going out of print. The early 1970s saw the peak of the occult revival which had begun in the previous decade, and which made room in publishers’ lists for odd little books like this one. Secondhand copies are still floating around although they’re seldom cheap. If you do find one just be careful who you lend it to.