Adolph Sutro’s Cliff House in a Storm (c. 1900) by Tsunekichi Imai.

• Good to see a profile of Wendy Carlos, and to hear that she’s still working even though all her albums (to which she owns the rights) have been unavailable for the past two decades. I’d be wary of praising Switched-On Bach too much to avoid giving new listeners a wrong impression. The album was a breakthrough in 1968 but was quickly improved upon by The Well-Tempered Synthesizer (1969) and Switched-On Bach II (1973). And my two favourites, A Clockwork Orange – The Complete Original Score (1972) and the double-disc ambient album, Sonic Seasonings (1972), are superior to both.

• “[Sandy Pearlman] told me that one of the main inspirations was HP Lovecraft. I said, ‘Oh, which of his books?’ He said, ‘You know, the Cthulhu Mythos stories or At The Mountains Of Madness, any of those.'” Albert Bouchard, formerly of Blue Öyster Cult, talks to Edwin Pouncey about BÖC’s occult-themed concept album, Imaginos (1988), and his affiliated opus, Re Imaginos.

• More electronica: Jo Hutton talks to Caroline Catz, director of the “experimental documentary” Delia Derbyshire: The Myths and Legendary Tapes.

• At the V&A blog Clive Hicks-Jenkins talks to Rebecca Law about his award-winning illustrations for Hansel and Gretel: A Nightmare in Eight Scenes.

• New music: Archaeopteryx is a new album by Monolake; What’s Goin’ On is a further preview of the forthcoming Cabaret Voltaire album, Shadow Of Fear.

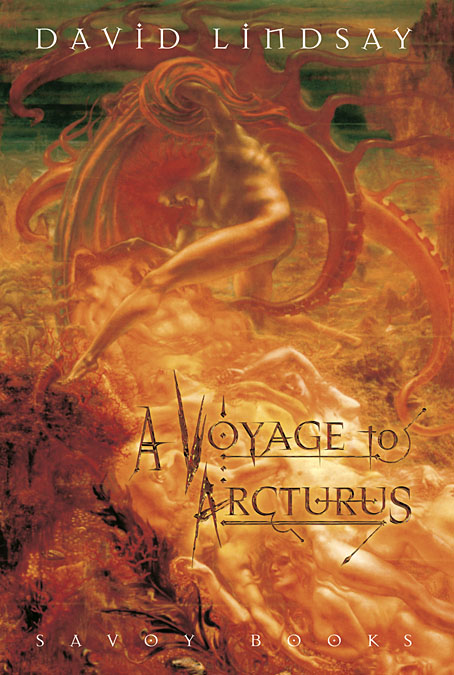

• Celebrating A Voyage to Arcturus: details of two online events to mark the centenary year of David Lindsay’s novel.

• “Streaming platforms aren’t helping musicians – and things are only getting worse,” says Evet Jean.

• At Spoon & Tamago: the cyberpunk, Showa retro aesthetic of anime Akudama Drive.

• At A Year In The Country: a deep dive into the world of Bagpuss.

• Sinister Sounds of the Solar System by NASA on SoundCloud.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Shirley Clarke Day.

• Mary Lattimore‘s favourite albums.

• Solaris, Part I: Bach (1972) by Edward Artemiev | Bach Is Dead (1978) by The Residents | Switch On Bach (1981) by Moderne