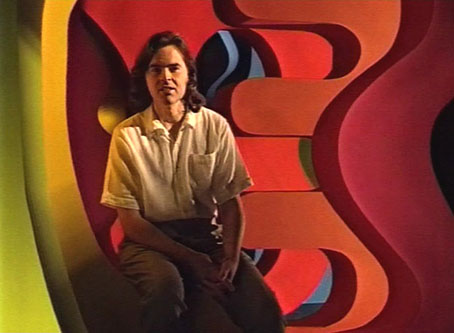

Browsing Vimeo recently I found a film by Anna Thew, Cling Film, which I remembered seeing years ago on Midnight Underground, a TV series devoted to avant-garde cinema. The series was broadcast by Channel 4 (UK) for eight weeks in 1993, with each episode being screened shortly after midnight. The presenter was the always reliable Benjamin Woolley, sitting before a backdrop resembling one of Verner Panton’s psychedelic environments from where he introduced the cinematic offerings, an eclectic blend of avant-garde and experimental films, unusual dramas plus a couple of animations. Episodes ran for around an hour, with each installment following a different theme. The films were a mix of the old and the new: “classics” (for want of a better term) of underground cinema set alongside more recent works. This was very much a television equivalent of the screenings of avant-garde cinema which Film and Video Umbrella had been touring around Britain’s arthouses since the mid-1980s; one of the founders of FVU, Michael O’Pray, is thanked in the series credits. Midnight Underground was so tailored to my interests at the time it was easy to feel like this was being screened for my benefit alone. I taped everything as it was broadcast but I never got round to digitising all the episodes, so that many of the films shown there, Cling Film included, I haven’t seen for a long time.

Benjamin Woolley.

The discovery of Anna Thew’s film set me wondering whether it would be possible to replicate the contents of Midnight Underground via links to various video sites. Since this post exists, the answer is obviously yes, or almost… Of the 44 films shown in the series only 3 are currently unavailable, with one more being limited to an extract and another as pay-to-view. This was a much better result than I expected, especially for works with such a limited appeal. The majority of the films shown in the series were being screened on British TV for the first time, also the last time for most of them. In 1993 Channel 4 was still maintaining its original brief, offering a genuine alternative to the programming on the other three terrestrial channels. As I’ve often complained here, this didn’t last; the underground remained underground. Woolley’s series was a brief taste of a televisual world where the concept of diversity could apply to form and content as well as identity. It’s a world the corporate channels will never show you, one you have to find for yourself.

* * *

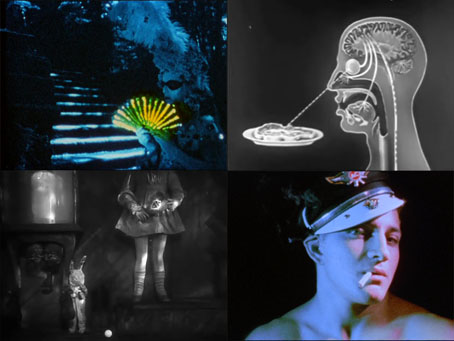

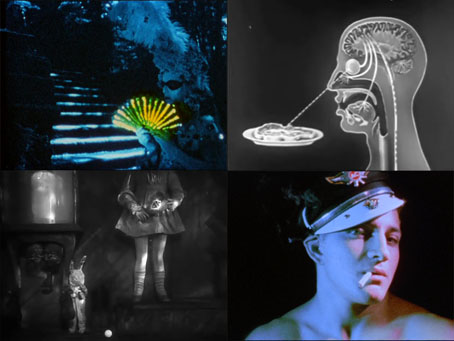

1: Strange Spirits

The opening episode shows why I felt they were broadcasting this for me alone. Derek Jarman’s grainy film of a Throbbing Gristle performance is probably the first (and only?) time the group appeared on British TV. This was the first surprise. The second one was Kenneth Anger’s film being shown with its Janácek score. I’d seen this at an FVU screening a couple of years before with its ELO soundtrack, the so-called “Eldorado Edition”, which Anger later discarded. As for Daina Krumins’ weird and creepy religiose short, I expected this one to be unavailable but the director now has several of her films on YouTube. Don’t miss her even-weirder animated slime moulds, Babobilicons. The angel in Maggie Jailler’s film is artist (and Jarman/TG associate) Cerith Wyn Evans.

• TG: Psychic Rally in Heaven (Derek Jarman, 1981)

• The Divine Miracle (Daina Krumins, 1973)

• Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (Kenneth Anger, 1954)

• L’ange frénétique (Maggie Jailler, 1985)

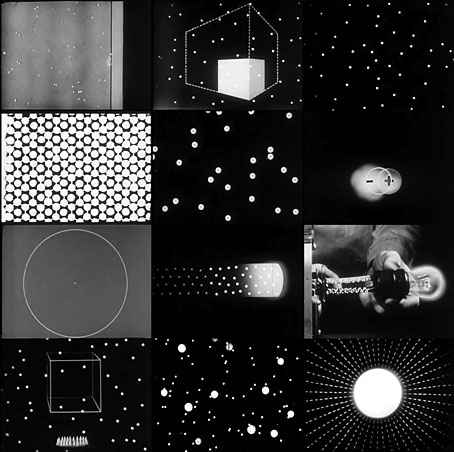

2: Music for the Eye and Ear

Bruce Conner’s films are continually elusive on the internet, especially those made to accompany music by Devo and Eno & Byrne. The version of Mongoloid linked here differs slightly from the original but it’s essentially the same film. Versailles II is taped from the Midnight Underground broadcast, and includes Benjamin Woolley’s introduction.

• Eaux d’artifice (Kenneth Anger, 1953)

• Mongoloid (Bruce Conner, 1978)

• Versailles II (Chris Garratt, 1976)

• Stille Nacht II: Are We Still Married? (Quay Brothers, 1992)

• All My Life (Bruce Baillie, 1966)

• Scorpio Rising (Kenneth Anger, 1964)

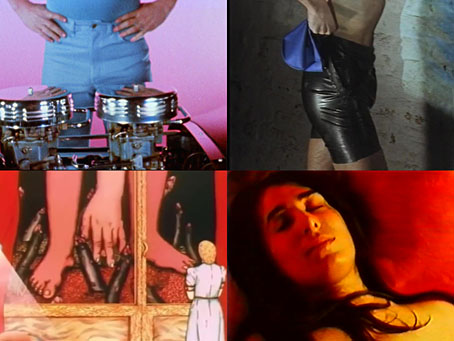

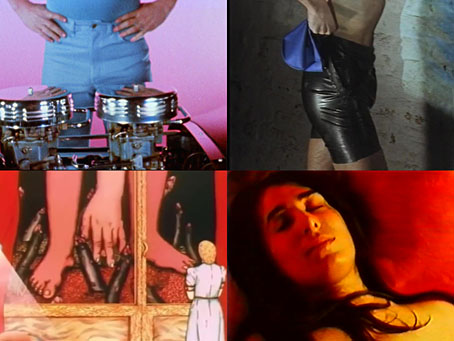

3: New Sexualities

Stephen Dwoskin’s film is the one that shows a close-up of a woman’s face during the act of masturbation. This is paralleled later in the series by Antony Balch’s masturbatory self-portrait in Towers Open Fire. Cling Film is all about safe sex, and was broadcast in a slightly amended form to avoid being too explicit. The version on Vimeo is uncensored.

• Kiss (Chris Newby, 1992) (no video)

• Kustom Kar Kommandos (Kenneth Anger, 1965)

• Cling Film (Anna Thew, 1993)

• Stain (Simon Pummell, 1992)

• Asparagus (Suzan Pitt, 1979)

• 6/64: Mama und Papa (Materialaktion Otto Mühl) (Kurt Kren, 1964)

• Moment (Stephen Dwoskin, 1969)

4: London Suite

Sundial and Mile End Purgatorio have both appeared here before as a result of my seeing them on Midnight Underground.

• Latifah and Himli’s Nomadic Uncle (Alnoor Dewshi, 1992)

• Sundial (William Raban, 1993)

• The London Story (Sally Potter, 1987) (pay-to-view)

• Mile End Purgatorio (Guy Sherwin, 1991)

• London Suite (Vivienne Dick, 1989) (no video)

Continue reading “Into the Midnight Underground”