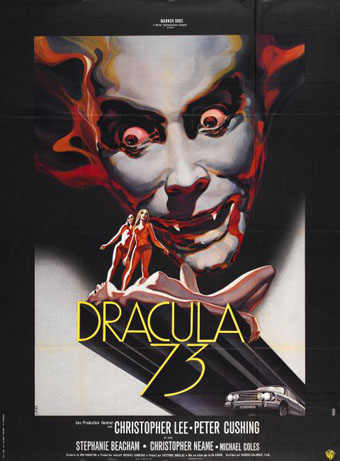

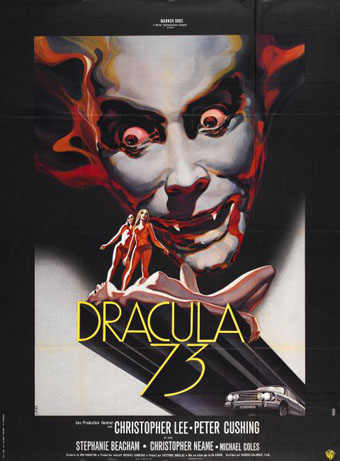

Impossible, not to say foolish, to attempt a brief summary of Christopher Lee’s incredible life and career. Rather than compete with the obituaries, here’s something you won’t find elsewhere, a short piece by Lee himself about his relationship to the role that made him famous. This is taken from The Dracula Scrapbook, a collection of Dracula and vampire-related cuttings assembled by Peter Haining for New English Library in 1976. The Lee piece was originally written for Midi Minuit Fantastique, Éric Losfeld’s film magazine which, we’re told, ceased publication in 1971. Haining dates Lee’s article as 1973 so I’ve left it undated, although it does seem to have been written around the time he was making (or had made) Dracula AD 1972. To compound the confusion, the poster above is for that very film but titled Dracula 73. Lee preferred Jesús Franco’s Count Dracula (1970) to the two final Hammer Draculas but the latter have their enthusiasts.

*

DRACULA AND I by Christopher Lee

I should certainly be pleased to play the part of Dracula again on the screen (surely it is the immortal role par excellence?), although I have many times refused to accept it. Nowadays I think the public identifies me with this part, and if I have sometimes refused it, it was for fear that, like the unfortunate Bela Lugosi, I should spend the rest of my life unable to play anything else. However I would willingly play it again, always provided that the production and scenario of this great subject satisfied me to the full. In any case, I have no intention of playing it to gain some sort of cheap publicity or for the financial benefit of a group of individuals incapable of appreciating or understanding the great power and the classical style of this great subject.

The part is one which needs to be played with respect and dignity, although one must always consider the commercial angle, which nowadays cannot be ignored.

I wrote recently that a true actor ought to be able to play a great diversity of parts. I think I have proved this as far as I am concerned, and that consequently there is no danger for me of being ‘typed’. But I am first and foremost an actor and must earn my living, and if the occasion arises again I shall he delighted to play the part of Dracula again under conditions which satisfy me.

Above all I should wish my interpretation to be more faithful to the novel of Bram Stoker. It seems to me that in the film Horror of Dracula (which, by the way, was excellent and a great success) the scenario left in the shade some aspects of the novel which, if they had been retained, would have improved the film as a whole considerably. For example, the sequences with the wolves and the capital scene with Jonathan Harker and the mirror, not to mention the boat sailing for England. The omission of Renfield was also very regrettable.

I believe that these scenes were not shot for financial reasons; they would have made the film considerably longer and therefore called for a great increase in the production budget.

It may surprise you to know that I have not seen any of the other versions of Dracula. Most of them were produced when I was very young and my age did not allow me to go to see them. But I think this is an advantage in my case, for above all I should not like to be influenced in my approach to the part by those who preceded me, even by the great Bela Lugosi. It will always be a cause for great regret to me that I never met him, whereas I know Boris Karloff very well and have a great admiration for him.

My personal idea of the interpretation of Count Dracula was of course based on the novel which I have read over and over again, and within the framework of the scenario and the production I have tried to give my personal view of its interpretation.

Bram Stoker’s grand-daughter came to see me on the set during the shooting, and was kind enough to assure me that my interpretation was excellent, and that she was sure her grandfather would have appreciated it.

Of course there was a great difference between the scenario and the novel, but I have always tried to emphasise the solitude of Evil and particularly to make it clear that however terrible the actions of Count Dracula might be, he was possessed by an occult power which was completely beyond his control. It was the Devil, holding him in his power, who drove him to commit those horrible crimes, for he had taken possession of his body from time immemorial. Yet his soul, surviving inside its carnal wrapping, was immortal and could not he destroyed by any means. All this is to explain the great sadness which I have tried to put into my interpretation.

Another problem was involved in the interpretation, a problem of a sexual nature. Blood, the symbol of virility, and the sexual attraction attached to it, has always been closely linked in the universal theme of Vampirism. I had to try to suggest this without destroying the part by clumsy over-emphasis. Above all, I have never forgotten that Count Dracula was a gentleman, a member of the upper aristocracy, and in his early life a great soldier and leader of men.

Of course it was impossible, within the limits of the scenario, to show this, but it is still possible by one’s interpretation to suggest the facts of the past without actually showing them.

As I have already told you, I am quite in favour of the idea of playing the part of Count Dracula again, always provided that the period and the Gothic atmosphere of the novel are respected.

I believe it is perfectly possible for a production of a film on this subject to be made in a modern setting, but there is only one Dracula, and his period must not be changed under any circumstances.

I have not read the whole of Bram Stoker’s work; I have only read (apart from Dracula) The Lair of the White Worm and one of his shortest stories, The Squaw. The first could not be screened, but the second in a shortened form would make an extraordinary film. The Squaw is, moreover, one of the most terrifying stories that Bram Stoker ever wrote.

The part of Count Dracula was one of the great opportunities of my career, and earned me a worldwide reputation.

It is one of the greatest parts ever created, one of the most famous and fantastic…no actor can ask more. •

Midi Minuit Fantastique

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Dracula Annual

• Nightmare: The Birth of Horror

• Albin Grau’s Nosferatu

• Count Dracula

• Symbolist cinema