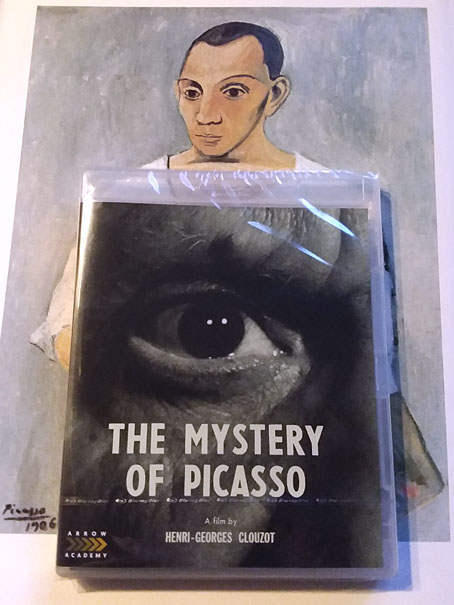

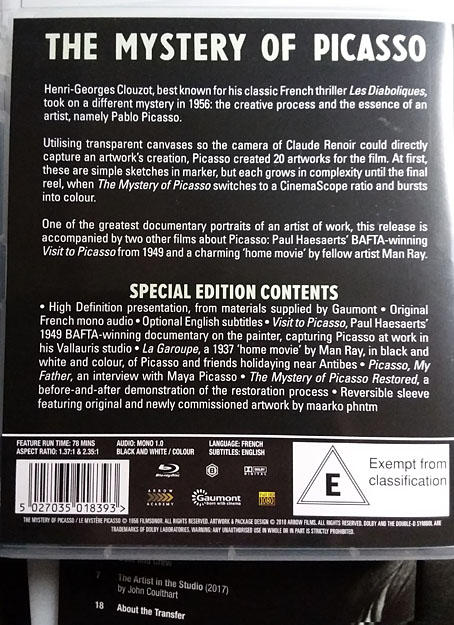

I mentioned late last year that I’d written the booklet notes for a forthcoming DVD/blu-ray of The Mystery of Picasso (1956) by Henri-Georges Clouzot, a film receiving its blu-ray premiere this month courtesy of Arrow Academy. The discs are now on sale (UK only, I’m afraid) either online or anywhere that stocks Arrow titles. (Fopp is my preferred outlet.) For those outside the UK, the restored film is also available on iTunes. Clouzot’s film was regarded as an oddity in the 1950s, the director being best known for outstanding thrillers like The Wages of Fear and Les Diaboliques. Today The Mystery of Picasso is regarded as one of the great films about art for the way it successfully captures Picasso in a decade when he was still fervently productive, despite being in his 70s.

Almost all films of this type favour the documentary approach, usually with a camera and interviewer dogging the subject’s footsteps while showing little of the creative process. Picasso wouldn’t have participated in anything like this—he was appalled by a documentary he saw about Matisse—but Clouzot persuaded him that a film could be made showing him drawing and painting in a studio environment. This approach had precedence in Paul Haessarts’ short film from 1949 (included among the disc extras) which showed Picasso in his studio at Vallauris; the film ends with a series of paintings on glass of various animals and human figures. Clouzot expanded on Haessarts’ idea with the full range of film technology: time-lapse, black-and-white stock, colour stock and Cinemascope. The works Picasso creates for the camera aren’t his best—how could they be when they were being produced at speed in sweltering, time-constrained conditions? But the film is a miraculous portrait of an artist whose name is still universally recognised almost fifty years after his death. By chance or design, it’s also a partial portrait of Clouzot himself who appears in several of the shots to discuss new camera setups.

There’s no need for me to say more about the film when I discuss it at length in the booklet. For a review of the disc contents, there’s a substantial appraisal here. For more about Henri-Georges Clouzot I recommend the study by Christopher Lloyd which was invaluable for its details about the film’s production.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Picasso-esque

• My pastiches

• Cubist Cthulhu